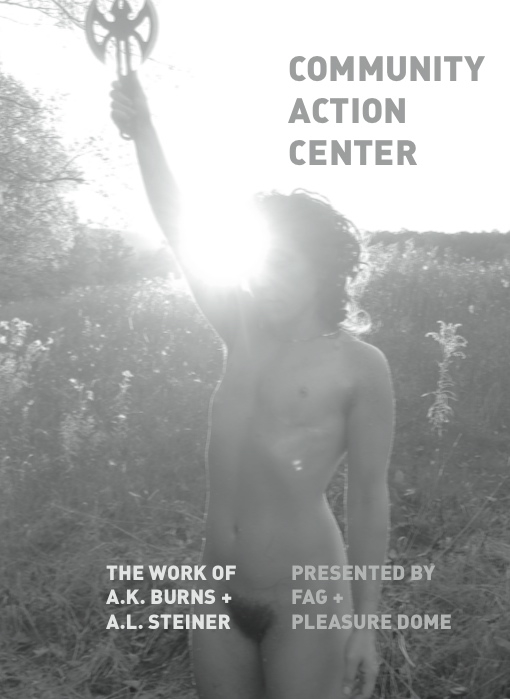

2011, Community Action Center.

Edited by Julia Paoli. Texts by Julia Paoli, and A.K. Burns & A. L. Steiner. Artwork by FASTWURMS, Deirde Logue and Allyson Mitchell. Interview with A.K. Burns & A. L. Steiner by Lauren Cornell. 32 pages.

Out of stock

Community, Community Action, and Community Action Center

Essay by Julia Paoli

A.K. Burns and A.L. Steiner’s sixty-nine minute video Community Action Center is both an exploration of queer sexuality and a celebration of human desire. The work features an intergenerational cast of artists, musicians, performers and dancers, all of whom make up a dynamic community of cultural producers. Community Action Center was made by and for “womyn and queers,” and also represents this community’s response to the lack of women-centered pornography produced by an industry which remains bound by assumptions of heteronormativity and the male gaze. Feminism and the production and reception of pornography share a complex history of cultural debate, with two strikingly different positions being traditionally associated with feminism. The first of these is an anti-pornography stance, which holds that the production and consumption of pornography establishes and perpetuates a causality of violence against women. The second of these is a pro-pornography sex-positive position, which holds that pornography and sexual freedom are essential to women’s liberation. Out of the rubble of these arduous debates is Community Action Center, a clear celebration of sexuality and eroticism.

Throughout the work, Burns and Steiner successfully dissect and reference common tropes depicted in mainstream pornography while avoiding the usual suspects for sexual stimulus. The result is a visual demonstration of sexual liberation. We bear witness to a series of erotic entanglements between the characters and catch a glimpse beyond the paradigmatic boundaries of heteronormative desire. Above all else, Community Action Center is an intimate representation of a collective of friends and lovers. Burns and Steiner offer us a depiction that invokes a contemporary queer/trans sociality and elicits a re-consideration of the meaning of community participation.

Collaboration is an important strategy for Burns and Steiner. Both are members of an expanding community of feminist, queer and genderqueer artists and cultural producers, many of whom frequently collaborate and exhibit their work together. If we trace the history of both artists’ practices, it would seem that their contributions to the annual feminist queer art journal LTTR may have served as a formative moment for each – both in articulating their shared interest in feminist and queer politics, and in building a community of creative individuals.

Both Burns and Steiner contributed to LTTR which was founded in 2001 by Ginger Brooks Takahashi, K8 Hardy and Emily Roysdon. It rapidly grew into one of the foremost genderqueer1 collectives in New York City. Their title was a shifting acronym, initially meaning “Lesbians to the Rescue,” and later stood for phrases including “Lacan Teaches to Repeat” and “Let’s Take the Role.” Just as the meaning behind LTTR varied over time, so too did the contributing membership and the editorial board: in 2005 the journal welcomed new editor Ulrike Müller to the team and invited Lanka Tattersal to act as a guest editor for the fourth issue.2 In that issue, contributors were asked to speak about their wish to direct the journal in their submission process. Normally LTTR followed an open call for submissions policy, with selected entries decided upon by the journal’s collective editors. For this issue, the curatorial collective Ridykeulous, comprised of Steiner and artist Nicole Eisenman, submitted a response entitled “Who do You Think You LTTR?”3 Since 2005 Ridykeulous has been using this same sense of humour, describing their work as an effort to “subvert, sabotage, and overturn the language commonly used to define feminist and lesbian art.” The text published in LTTR was made up of questions, criticisms and reprimands against the journal, asking the editors to recognize their role in a process of systematic judgment that is performed within an imperfect heteronormative structure.

In late 2006, LTTR published its fifth and final issue. Although the collective no longer formally exists, many of its former contributors remain friends and collaborators. For instance, beyond the partnership on Community Action Center, Burns and Steiner, alongside artist K8 Hardy, are founding members of W.A.G.E. (Working Artists and the Greater Economy), a collective that aims to “draw attention to economic inequalities that exist in the arts, and to resolve them.”5 In 2010, Burns, together with Sophie Mörner, published the first issue of Randy magazine, a publication that brought together the work of artists including Cass Bird, Lee Maida, MPA, Ulrike Müller, Sheila Pepe, Celeste Dupuy-Spencer, Ginger Brooks Takahashi and Wu Tsang.6 The result of these and other collaborative efforts is an expanded creative network. If we consider the preceding examples, it becomes evident that despite the fact that many projects are attributed to one artist – as if they were wholly a product of a single artist – that many works depend on the participation of members of the larger network. Together these individual practices make up a vibrant artistic community whose desires and eroticisms are explored and celebrated throughout Burns and Steiner’s Community Action Center.

After watching Community Action Center, one might instinctively return to questions of representation. Popular culture subsumes an image or an individual in an effort to represent a group to a wider audience. In contrast, Community Action Center refuses to present a single unifying representation of feminist and queer identity; more specifically, the work is not simply a display of lesbian separatism or sex-positive feminism. Burns and Steiner offer their performers, characters and viewers alike, the unending freedom to inhabit various states of desire that refuse boundaries and defy expectations. The inclusion of members from the artists’ close-knit community signifies a refusal to represent or speak for a broader queer audience. The work is far more attuned to exhibiting and affirming the sex that partially defines this specific community. As a result, Community Action Center is able to carve out a space where performers are free to act out their desire, and viewers are invited along for the ride. It is through this liberating aesthetic that we are able to have moments of identification with the action on screen.

While cultural norms suggest that consumers of pornography ought to do so in private settings, Community Action Center situates pornography squarely within the public sphere. Screenings of the work create a space for discursive activity wherein viewing communities may come together to explore questions of representation, politics of sexuality and liberated desire. Viewing the work together may lead us to a series of questions about our own communities. How might we transition from talking about a single community at a given screening, to importing the lessons offered by that given screening to community-specific interpretations? How might the energy from Community Action Center translate from city to city? How do members of genderqueer communities in other places, in other contexts, read and relate to the work? But perhaps before one can even attempt to answer these critical provocations it is best to begin where Burns and Steiner did. At the heart of Community Action Center is the freedom to think about your own sexuality and ask: what are your preferences and visceral reactions to the work? It is through answering that question that we can begin to honestly celebrate all that Community Action Center has to offer, and begin re-considering the community that we are connected to in our own lives.

1 The term genderqueer encompasses all those who fall outside the traditional gender binary and refuse the cultural codes that perpetuate normative sex and gender boundaries.

2 LTTR. “About LTTR.” http://www.lttr.org/about-lttr

3 Ridykeulous, “Who Do You Think You LTTR?,” LTTR, no. 4 Do You Wish To Direct Me?(September 2005): 5.

4 W.A.G.E. “W.A.G.E. (Working Artists and the Greater Economy.”http://www.wageforwork.com/wage.html

5 Randy: The Lesbiandyketrannyfag Artzine. “About Randy.” http://randyzine.com/about