Tropic of Kika: an interview with Kika Nicolela

(May 2017)

Mike: Could you tell me something about your beginnings? Some speak of their work as a kind of calling, as if they were following a voice, while others begin making movies from the ruins of a painting practice, or even the ruins of a relationship, a failed touch. Why movies? Were they always your friend?

Kika: Movies were always my friends. Maybe my only friends at times… I grew up on musicals and film noir from the 1940s and 1950s. That was my world, and it conspired to make me even a bit weirder and more isolated from other children and, later, teenagers. It made me want to go to university to study and write about movies. Until then I was not a maker, only a cinephile.

At university I discovered the art of making movies. While I was fascinated by the whole thing — the moviola, the film camera, the lights, the celluloid itself — I confess that only when I could do things alone, more independently, that’s when I started to make my stuff. Meaning: when I could have a smaller, more affordable video camera and edit on my laptop. Unfortunately in São Paulo there is not a super 8 scene like there is in Toronto. I never learned how to process film myself, so film was always too expensive.

Before starting to find my voice with video, I worked as an assistant director for a big movie. From the script to the shooting it was a four-year process that taught me a lot and marked me profoundly. But I was more interested in analyzing it, rather than being a part of the film business. I decided that was not my life.

A moment came when I threw away all of my film training and try to do something else with a camera and editing. That’s when I started collaborating with dancers, making something that could be called video dance works, and also with artists, doing what might be called video art. But at first I did not know what I was doing. I was not giving it names, I was just falling in love with creating works that were hybrid, weird, open and cheap/fast to make. Instead of taking years between thinking about work and making/showing it, sometimes I had just a few months. I was “giving my face to be slapped,” an expression in Portuguese that means opening yourself to be criticized and/or admired. I was always afraid of showing my personal works, but I decided I had to do more and more, be less of a pussy about it. Just do it. Learn. Move to the next project. Be open to new collaborations, invitations. One day somebody said I was an artist and I believed. Can we call all this my beginning?

Mike: In Toronto there is a code of politeness that insulates artists from critiques. There can be withering judgements, but these are usually offered afterhours in the bar, when the artist is far away. How do you receive feedback on your work? How do you know if it’s flying or even if it’s finished? And: what is the most surprising feedback you’ve ever received?

Kika: Very seldom do I receive real critiques on my work. Most art critics are now “for hire” — so we (artists or art institutions) invite them to write an essay for an exhibition catalogue, for example. While it is great to be able to choose a person that we think might appreciate or look upon our work with an interested regard, I find it strange that we rarely receive a spontaneous in-depth critique.

At an opening or screening I obviously feel when the work is more or less appreciated, and sometimes I do receive harsh feedback. It is hard to deal with it in these situations because it’s when I am most vulnerable. But I still appreciate when the words are honest and constructive.

The most rewarding feedbacks are spontaneous. Once I had a screening with 7 or 8 of my films. In the middle of it, a person from the audience, an artist, left the room. I went out later and she was outside crying. She hugged me and cried for minutes. She only said, “Thank you.” That was a reaction triggered by a film of mine shorter than three minutes. I thought it was amazing, wonderful, how such a small film could open such a big space inside a person. Her meltdown was one of the nicest compliments I received because I could feel it was important to her.

Mike: For those of us who have never been to Brazil, could you offer us a snapshot of the scene? Are there many folks making movies? Is there a hard split between the experimentalisms that you’ve embraced and other kinds of making? Are there regular screenings, orgs and venues, or is it more pop up and provisional? Is it a small place where everyone knows each other? Are there more artists working today than ever before? Are there revered figures from the past, or is there no way to keep the past in view so everything is always new?

Kika: It is almost impossible to offer a snapshot of the Brazilian scene. Brazil is so big and its regions are so different from each other that all I can try to do is to give an idea about São Paulo where I am from. It is a town that is almost a country, its 20 million people are more than twice the population of Belgium where I currently living 60% of the time, though I still spend a lot of time in Brazil.

The other reason why it’s hard to talk about a Brazilian cultural scene is because the country is going through a very complex political/economic process that is directly affecting the art market and government politics concerning art and culture A lot of the sector’s achievements over the past 15 years are being destroyed or put on hold by a narrow-minded neo-liberal government. We are living in limbo.

There are different and important scenes in Brazil’s different towns. Most things happen in São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro, they attract artists and people from all over the country, a bit like New York/Los Angeles in the US, or Toronto/Vancouver/Montreal in Canada. But other very interesting towns have a vibrant artistic scene like Recife, Belo Horizonte, Porto Alegre, Salvador… They have much less money and visibility but sometimes interesting movements are born there. For example Belo Horizonte has been home to many amazing video artists partly because in the 80s they had no money or access to film, so they “went video” instead. I don’t think that’s the only reason (I joke there must be something in the water that makes great video artists). Maybe it’s the very conservative society that creates a radical scene in reaction to it, and being so much smaller than São Paulo helps them stick together more tightly.

I live between two different art scenes — film and contemporary art. There is not a real experimental film or even video art scene today, though there used to be an important video art festival called Videobrasil. Unfortunately this festival changed its nature and became a contemporary art showcase, with broader tastes and mandates but it’s become less relevant for the local video art community. I find myself always in-between scenes and while that grants me a certain mobility, I never feel comfortable in one place. Now I’m even living in two countries. That’s the story of my life.

I came from the film scene and began at the most important film school in the country at the University of São Paulo. I was part of the last generation to learn how to use film and moviolas. In 2000 when I finished university the commercial film scene was starting to get back on its feet thanks to important new laws (related to tax reduction for cultural investment) and government-supported funding. São Paulo was especially favored because it is a rich town and province. That led to a growing number of films and TV series produced every year. Many film festivals started all over the country. I worked a bit in the film business as an assistant director, but it soon became clear to me that I wanted to make films in a more independent manner.

When I started to make my videos in 2003-2004 I found two ways of showing them in two different scenes: video or film festivals (which at the time were just starting to accept video) and art exhibitions. São Paulo is composed of different art scenes: an institutional one, a commercial one and an independent one. I was involved in all three, but for a few years now I am no longer represented by any commercial gallery. Our art market grew a lot, with dozens of art galleries opening up in the last eight years. But since the crisis many galleries have closed or downsized in the past year. The government-supported institutions are also feeling the crisis, some are closed, while most (or all) had their budgets cut and are being forced to change their programs. It is still very important for the survival of the artists in São Paulo, but I don’t know how long that’s going to last. My feeling is that the independent scene is going to grow a lot because the rest is so fragile. The survival of the artists is really at stake.

The biggest problem is not the economic crisis itself in my opinion. The new governments (federal and municipal in the case of São Paulo) are strictly neo-liberal and support cuts to culture and even education instead of working on the real problems of this unequal society.

We artists are half in despair and half optimistic that this identity crisis — for it is more an identity crisis than a political or economic one — will eventually trigger a strong reaction that could lead to a major change in the way our society functions. Most artists are aligned in this view. I am not a political person normally. But I’ve started to think that making art is already a political choice. Although the way the art market works is perverse and makes us dependent on a rotten system. That has to change too. Right now everything is falling apart — funding, institutions, festivals — and there is not even a dialogue about it. The first thing the new president did was to close down the Ministry of Culture. There was a huge outcry and he was forced to change his mind, but he cut a lot of its funding and projects.

Groups of artists have begun to talk about a future organization that could protect our rights. I participated in one meeting and gave the Canadian example of CARFAC (Canadian Artists’ Representation/Le Front des artistes canadiens). That could be a model for us, but we are a long way from that.

Mike: You spoke about being at home in an in-between place. I’m wondering if you could tell me about your swooningly perfect portrait doc Tropic of Capricorn (30 minutes 2005)? It looks at the lives of four trans women in a very intimate way. Why did you bring them all to this hotel room? Why this subject, these faces, these stories?

Kika: Like many of my earlier works it started with an invitation. I was asked to take part in a group show inside a decadent hotel in downtown São Paulo. It was located in a region that was once chic and fancy, but since the 70’s it had become a zone for prostitution, prostitution of transexuals in particular. I decided that I wanted to make a site-specific installation, relating the hotel’s bedroom to its surroundings. I wanted to do “programs” with the prostitutes, inviting them to come with me to the hotel bedroom, while making it clear that this was an art project.

I had come from an experience of making a documentary about black women who work in the carnival parade. Although I was happy with the project – it was a strong experience for me – it made me realize the limitations of the interview as a tool. In Tropic of Capricorn I wanted to take myself out of the relation between subject and camera. I was not interested in posing questions. I did not want them to reply to my words and presence. I wanted them to respond to the situation. That was the first time I realized that I could set up a situation and lose control of how things would turn out. I didn’t know how things would unfold.

At first, I thought that first night would be just a test. But it became the final shooting. I invited them one by one, and explained that there was a camera on the ceiling, and that I would leave them alone in the hotel bedroom. They could do or say whatever they wanted, but they had to stay on the bed for the length of the “program” (about 40 minutes). Those were the parameters.

I shot this in 2004, in a pre-selfie generation. Now people are used to making this kind of self-performance for the camera, thanks mostly to smartphones. At the time, webcams were just starting to spread. Now everyone is a content-maker and an exhibitionist. But at the time, the role of the public was more concerned with voyeurism.

Watching the footage afterward was like discovering treasure. I was fascinated by how their body expressions and discourse changed over time. Time is a crucial element in this project. They were prompted to create something, to perform, since I had no specific directions for them. I was particularly touched by the “blue” woman. After some talk and touching herself, she says something to the camera: “I wonder what you are thinking about me? Do you think I am a whore? I would love to look into your eyes and see what you are thinking about me. Would I understand you?” It’s as if she’s turned the camera around and pointed it at the spectator. It’s interesting to note that out of the four participants, two treat the camera as “you,” but the other one uses “vocês” (you in plural), while this one is always talking to a singular you. She implicates the spectator in a very intimate relationship, one in which the spectator is no longer invisible, making him/her as vulnerable and exposed as she is. Later I came across the brilliant work of Vito Acconci and realized he was doing a lot of that, but in a consciously constructed way. Another important subject that emerged was the relationship between fiction and reality. While they are “real” people, their speech and actions are obviously constructed. They all touch themselves in a very fake way. We have no idea if the stories they tell are true or not. The “yellow” woman starts by playing the seducer, very much at ease with being a sex professional. Later she interrogates the profession and those who seek her out, reflecting on the roles they play.

I became aware of the question of authorship, perhaps I’m once again in an in-between place. I like to share the authorship of the work with the participants. Even if the idea, editing and output are defined by me, the content is created by the participants. Tropic of Capricorn was the first project like that for me, but others came after dealing with similar issues.

Mike: More than a decade later you made Biographies (30 minutes 2016), a portrait of Domitila de Castro do Canto e Melo, the Marquise of Santos. It features five women who riff off of the central character, bringing her into the present in very unusual ways. I wonder if your relationship with the participants was another instance of ceding control and working collaboratively, and how you found your way to Domitila?

Kika: Biographies was another site-specific installation that became a single-channel video, like Tropic of Capricorn. These works have in common the fact that the place of exhibition determined my theme. The museum that commissioned the work used to be the house of the Marquise of Santos, a very interesting woman who died in the late 19th century. Like everyone in Brazil I had an idea of who she was, but once I started deeper research I was mesmerized by the legendary nature of her life story. For instance the encounter between her and the future Emperor of Brazil happened a few days before he proclaimed the country’s independence from Portugal. Her life story and the history of Brazil are intertwined.

I became interested in this question: how to represent a historical character? What does it mean to make a biography? How can anybody pretend to know how a person was and portray her? It’s hard even to know ourselves… imagine portraying somebody who died over 100 years ago.

I read everything about her and made a list of what I called “images” — either presumed facts, myths or merely gossip around Domitila — that struck me as the most arresting, as well as full of contradictions. I invited five actresses to choose images they could identify with, and that were close to them somehow. We then had two days together, doing improvisation exercises I proposed and others we created on the spot. And from that the scenes we were going to shoot were drafted.

Each scene was a mix between themselves and the character they were portraying. Some were more performance-based, some total improvisations, another had written dialogues. They were all amalgams of Domitila and the actress portraying her. The encounter and tension between the actress and the character was what I was interested in.

It was another instance of working collaboratively but in some scenes I had less control than in others. The kitchen scene was written (based on an improvisation exercise we had done together), so I was somehow more in control. The scene at the monument where the actress goes up the stairs with a bag full of rocks changed because it rained. For the bathroom scene I gave the actress some elements, but she took the improvisation to places I didn’t expect.

The biggest difference between a project like this one and Tropic of Capricorn is that there was a longer process of preparation. It involved research and a process with the actresses. And, of course, they were actresses, not “normal” people. However, in all my work with actors, I am interested in each one as a person.

I was lucky to have crossed paths with the Marquese of Santos. Not only is she a multi-faceted and complex character but she is a “real person” too, a historical character. So much fiction has been gathered around her, not only in films, soap operas, TV series, books, but also in gossip and legends. She was really the ideal character to think about representation, truth and history.

There are a few houses related to her, I visited and shot four of them. Two really belonged to her — one in Rio de Janeiro and another in São Paulo (which has been turned into a museum, and where the exhibition was held). There’s another house in Sorocaba where she went on a one week holiday, but it has also been turned into a museum dedicated to her on a street with her name.

Another house, on an old highway going to Santos (a coastal town that provided her title, Marquise of Santos, although she was never there) is famous because it’s the place where she had some love encounters with the emperor. Schools and tourist agencies promote cultural trips to this house. The fact that the house was built in 1922 — a fact written on its facade — does little to shake their beliefs. Domitila died in 1867, so obviously neither she nor the emperor were ever there. I heard this started as gossip decades ago by a guy who used to own a nearby restaurant, hoping people would drop by that forgotten highway. The restaurant is long gone, but the myth remained.

Mike: Your multi-screen installation Impressions of a Love Discourse (2013) feels like it’s following the same interactive groove, inviting performers to become part of the dance of creation.

Kika: Indeed it does. Until 2010, with the exception of my videodance pieces, I was interested in involving different kinds of people in the making of my films through participative methods. But I was not working with performers.

(By the way, just a parenthesis, I like the word performers, it’s interesting… in Portuguese, we never call the actor a performer, we use the word performer only in performance art. But I think we should call everybody who is in front of a camera, actor or non-actor, a performer.)

The first film I made that involved actors was Actus (17 minutes 2010). There was a script with actors, but I was interested in breaking down the acting. By watching actors perform repetitions of the same scene, the audience would start to see them as people negotiating a situation. I wanted to watch them trying to act, trying not to make mistakes, performing.

Since then all my work involving actors uses different strategies to involve them in the creation process. I want to be surprised. Actors find these projects challenging, different, sometimes difficult. They are sometimes more vulnerable than in films where they can “hide” behind the character. We are looking together for the fiction in life, and the life in fiction. Plus, I need them to be creators.

In Impressions of a Love Discourse I wanted to use a real person as a starting point to show how we all are multiple, how our identity is a construction, both by us and via the perception of others. I chose myself as this person, but it could have been anyone. Although, of course, using myself makes me the subject of the work as well, which again raises the question of authorship. And makes this piece a mix between a portrait and a self-portrait.

The strategy was simple: I had six actors interview me. Each had a one-hour conversation about my love stories from the past two years. I have to say I was in a very specific life moment at the time, in which I did not fully understood myself, my feelings and actions, what I wanted and why. Based on these conversations each actor created a character that would be a mix of me (as they perceived me), and their own life stories. They were then interviewed by another person — the director of their theater company by the way — and we recorded these interviews. The installation is composed of those recordings. They hang in the gallery, one vertical LED-TV for each portrait.

Mike: You’ve made a number of works that feature a single woman who struggles and moves wordlessly through a space. They are usually shot by elegant cinematographer Ching C. Wang and music/sound arrives via Thierry Gauthier, sometimes in collaboration with Delphine Measroch. It feels like your psychodrama dance crew is always at the ready to deliver these handsomely produced solo vehicles.

Crossing (9:03 minutes 2003) finds dancer Leticia Sekito gathering her molecules before heading across the street in a swirl of superimpositions, as if there were no feeling there that didn’t belong to her. In Flux (11:09 minutes 2005), a red-dressed Leticia Sekito scales a staircase and finds a horse in an open field, inviting her to touch and follow. In the luxuriously lensed Windmaker (10:52 minutes 2007) we follow Luciana Canton in a psychodrama set in the natural world. She looks tormented in a nighttime forest, and then barely stays afloat in a country lake. Naked (3:21 minutes 2008) is another performance miniature. Alessandra Cestac appears naked in light-filled glimpses, lying then standing and crossing a busy nighttime street. Entre-Temps (2016) took shape as an installation, showing a nightgowned Anna Tenta crawling across the floor. She is projected against multiple screens, fragmenting her attempts to rise and traverse. All of these works bring dance and psychodrama together in a performance setting where portraits of bodies twist in distress and dis-ease, filled with tension or abject struggle.

Kika: Each one of these works had a specific idea behind it, but to generalize I would say that it’s always a dialogue between the female body and its surroundings — be it an urban surrounding (Crossing), a forest at night (Windmaker), or old constructions that are filled with history and a kind of materiality to it (Flux and Entre-temps).

I don’t know if I would call them psychodramas. In these pieces, the women are not characters with a psychological struggle, with a past or a future, with a story. They are almost like archetypes, their struggle is ancient and symbolic. They always involve improvisation, the dancer and I “dance” together (it’s almost always me doing all or most of the camera).

Let’s take the recent Entre-temps as an example. It was shot in the empty building of the Jewish Museum of Brussels, in a cell once used as a Nazi prison. It is a place charged with history and the drama of human suffering. The dancer and I wanted to explore the idea of confinement with her body. The day we arrived for the shooting there was a special light coming into the small room. As she started to move inside it, we realised she was raising a lot of dust. That light and dust were elements that inspired us, so we kept shooting and dancing. It was really special. I found that the relationship between the shadows and the light was another way to explore the theme of confinement versus freedom. While I talk with the dancers before shooting, the work is created on the spot, in the moment, without rehearsal or repetition. They are almost always shot in one take, two at the most.

Mike: You’ve started up an international omnibus project, inviting artists to create segments that are joined to create touring feature-length projects. Can you talk about how that started, what you’ve produced, and how you choose the artists? You are also an avid contributor, perhaps you could write about some of your own mini-set pieces within the larger structures you’ve set in motion?

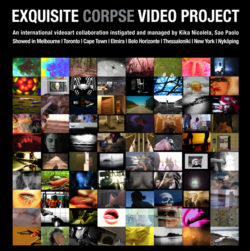

Kika: The ECVP (Exquisite Corpse Video Project) was born out of a need to connect and promote connections with other artists. It began just before Facebook. I often used a social networking site called Artreview, which was only for artists. I proposed making a few video exercises using the Surrealist game of “cadavre exquis” as a way to collaborate with artists from all over the world. Basically each artist makes a one-or-two-minute video, and then sends the last ten seconds to the next artist in the group. It forces you to be open to whatever you are going to receive from the previous artist. I like to change the rules of the game to keep it fresh for those who participate. It is still an exercise for artists, a game, although we have presented it a lot. But we have to keep it exciting.

How do I choose the artists? Some have been with the project since I first proposed it online. Sometimes I know the work and invite the artist to participate. Others are suggested by trusted members of the group. Some approach me, and if I like their work, I include them. People are already asking me about the next one… so maybe next year! But it is quite time consuming to coordinate the whole process.

We have done five volumes since 2008. The first and third volumes had no themes. The second volume had 12 different themes and was divided into a dozen 10-minute videos. The theme of the fourth volume was Porn and Politics, and for the fifth volume: Crisis and Utopia. The themes are very open to interpretation, and provoke various reactions from the artists.

Often the videos made for the ECVP become parts of longer videos on their own. Many projects began here. It is true for me too: Flickering (2:43 minutes 2009) was a piece of mine for the ECVP, and then I changed the editing a bit to give it an independent life. It’s also an example of how we come out of our comfort zone in this project. Flickering is the first video in which I perform an action in front of the camera. Many artists participated in every volume, they really got addicted to it. Sometimes I hear from an artist that the ECVP is very good to unblock them. The ECVP is also a place to experiment with new things, to try out stuff, to be less ambitious, to let go of our ego a bit.