Part of Fall 2007

This programme contains work by two artists: the series of short films and videos Pictures of Things That Aren’t There by Toronto-based artist Mary J. Daniel and assorted short films by the legendary American filmmaker Marie Menken selected by Daniel.

Pictures of Things That Aren’t There is an adaptable anthology of six short works loosely tied together by the circumstance of their making: all were initiated while the artist was caring for her mother as she lived out her life with a disease that erodes the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Her mother’s illness is never more than peripherally addressed. Daniel instead attends to the poetry and artistry of her own mind going about its daily business of living, using her experience of her mother’s illness as a source of inspiration for a set of cinematic studies of the unnoticed daily workings of the imagination – the capacity of mind she sensed her mother had lost.

Characterized by subtle colourings of emotion and light, Daniel’s films are like haiku poems, compact and oblique. They are still and meditative yet vibrate with nature and drama. Her one-take films form moving paintings. They are painterly compositions, landscapes and portraits, which bend the screen into a vitrine to confound the conventional and unconventional beauty she finds in the natural and familiar. Her deceptively simple films untangle the melee of quotidian concerns into essential pleasures and pains. They clarify life. Perched on the edge of nothingness, they are forays toward pure being where knowledge falters and meaning no longer requires it.

Like Daniel’s, Menken’s films are small, lyrical and immediate. Menken was a seminal figure in the New York experimental film scene of the 1950s and 1960s who influenced Andy Warhol, Stan Brakhage, Jonas Mekas, Kenneth Anger and Gerard Malanga, among others. Her small-gauge films exude an easy nonchalance as they wander over natural and the social worlds. “Freely, beautifully, they sing the physical world, its textures, its colors, its movements; or they speak in little bursts of memories, reflections, meditations.” according to P. Adams Sitney.

Program:

Glimpse of the Garden, Marie Menken

(1957, 5 min, 16mm sound)

Pictures of Things That Aren’t There

Mary J. Daniel

(2006, 29 min. video, sound)

1. this time last year

2. Parenthesis

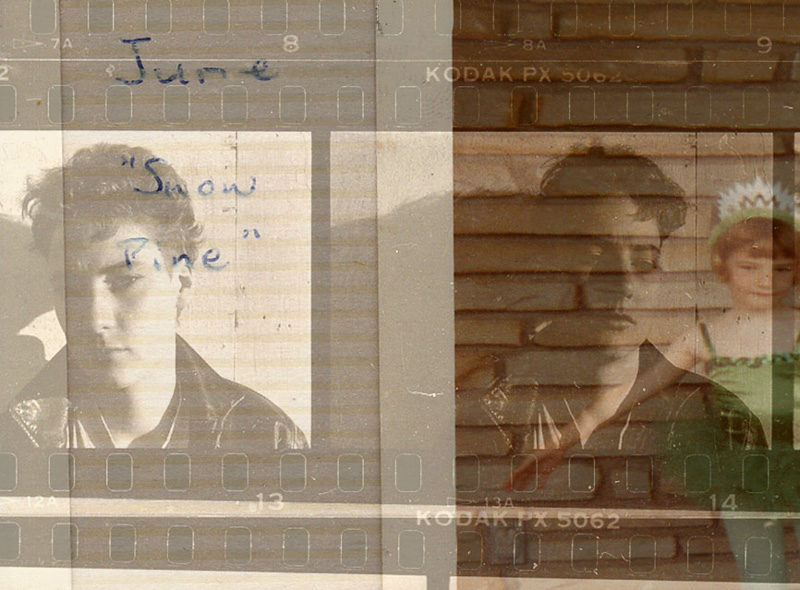

3. Confessions of a Compulsive Archivist

4. A Figure in the Ground

5. Two Hummingbirds

6. Two Unrelated Shots

Notebook, Marie Menken

(1962-1963, 10 min, 16mm, silent)

Moonplay, Marie Menken

(1964-1966, 5 min)

Hurry Hurry, Marie Menken

(1957, 3 min, 16mm, sound)

Sidewalks, Marie Menken

(1966, 6 min, 16mm, silent)

Excursion, Marie Menken

(1968, 5 min, 16mm )

Dwightiana, Marie Menken

(1959, 3 min, 16mm, sound)

Programme Notes:

Pictures of Things That Aren’t There

Short Works by Mary J. Daniel and Marie Menken

This programme contains work by two artists: the series of short films and videos Pictures of Things That Aren’t There by Toronto-based artist Mary J. Daniel and assorted short films by the legendary American filmmaker Marie Menken selected by Daniel.

Pictures of Things That Aren’t There is an adaptable anthology of six short works loosely tied together by the circumstance of their making: all were initiated while the artist was caring for her mother as she lived out her life with a disease that erodes the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Her mother’s illness is never more than peripherally addressed. Daniel instead attends to the poetry and artistry of her own mind going about its daily business of living, using her experience of her mother’s illness as a source of inspiration for a set of cinematic studies of the unnoticed daily workings of the imagination – the capacity of mind she sensed her mother had lost.

Characterized by subtle colourings of emotion and light, Daniel’s films are like haiku poems, compact and oblique. They are still and meditative yet vibrate with nature and drama. Her one-take films form moving paintings. They are painterly compositions, landscapes and portraits, which bend the screen into a vitrine to confound the conventional and unconventional beauty she finds in the natural and familiar. Her deceptively simple films untangle the melee of quotidian concerns into essential pleasures and pains. They clarify life. Perched on the edge of nothingness, they are forays toward pure being where knowledge falters and meaning no longer requires it.

Like Daniel, Menken’s films are small, lyrical and immediate. Menken was a seminal figure in the New York experimental film scene of the 1950s and 1960s who influenced Andy Warhol, Stan Brakhage, Jonas Mekas, Kenneth Anger and Gerard Malanga, among others. Her small-gauge films exude an easy nonchalance as they wander over natural and the social worlds. “Freely, beautifully, they sing the physical world, its textures, its colors, its movements; or they speak in little bursts of memories, reflections, meditations.” according to P. Adams Sitney.

Marie Menken (1909 – 1970) was one of New York’s outstanding underground experimental filmmakers of the 1940s through the1960s, inspiring artists such as Stan Brakhage, Andy Warhol, Jonas Mekas, Kenneth Anger, and Gerard Malanga. She was also an abstract painter who worked a day job at Time Inc. and appeared in several Factory films, including The Life of Juanita Castro and The Chelsea Girls.

“Who is your audience?”

Mostly people I love, for it is to them I address

myself. Sometimes the audience becomes more than I

looked for, but in sympathy they must be my friends.

There is no choice, for in making a work of art one

holds in spirit those who are receptive, and if they

are, they must be one’s friends. (Marie Menken, qtd.

in MacDonald 212).

[md note: I’d reply the same. used the quote at head

of my thesis paper].

When Glimpse of the Garden was shown at the

Cinematheque Fransaise in 1963, Jonas Mekas reported

that the French audience laughed at it, embarrassed by

the film’s benign simplicity. Suffice it to say that

Glimpse of the Garden represents Menken’s interest in

pure visuals and essentially feminine point-of-view. –

David Lewis, All Movie Guide

MD note: suffice it to say?

Marie Menken: “There is no why for my making films. I

just liked the twitters of the machine, and since it

was an extension of painting for me, I tried it and

loved it. In painting I never liked the staid and

static, always looked for what would change the source

of light and stance, using glitters, glass beads,

luminous paint, so the camera was a natural for me to

try&lrquo;” but how expensive!” (Menken, c. 1966)

“Film making was a natural evolution while I was engaged in painting, particularly since I was primarily concerned in capturing light, its effect on textured surfaces, its glowing luminescence in the dark, the enhancement of juxtaposed color, persistence of vision and eye fatigue,” Menken explains.

The filmmaker Jonas Mekas wrote, “Marie was one of the first filmmakers to improvise with a camera and edit while shooting. She filmed with her entire body, her entire nervous system. You can feel Marie behind every image, how she constructed the film in tiny pieces and through the movement. The movement and the rhythm&lrquo;”it is this that so many of us seized upon and have developed further in our own work. … And she gave us a new beginning. She took the film – the non-narrative film, the poetic film, the language of film – in a completely new direction, away from classic filmmaking and into a new adventure.”

“There is no why for my making films. I just liked the twitters of the machine, and since it was an extension of painting for me, I tried it and loved it. In painting I never liked the staid and static, always looked for what would change the source of light and stance, using glitters, glass beads, luminous paint, so the camera was a natural for me to try – but how expensive!” (Marie Menken c. 1966)

Mostly people I love, for it is to them I address myself. Sometimes the audience becomes more than I looked for, but in sympathy they must be my friends. There is no choice, for in making a work of art one holds in spirit those who are receptive, and if they are, they must be one’s friends. (Marie Menken, qtd. in MacDonald 212).

Overview

“Who is your audience?”

Pictures of Things That Aren’t There is an adaptable intermedia anthology of short poetic film and video works. It is a constellation of small meditations on the unnoticed everyday workings of the human imagination, inspired by the experience of caring for my mother as she lived out her life with frontotemporal dementia. Through the contrapuntal interplay of simplified cinematic elements&lrquo;”word and image, hearing and seeing, figure and ground, window and surface, movement and stillness, sequence and cycle, document and story&lrquo;”it offers both a set and a series of thematically overlapping explorations of the relationship between the imagination1 and our sense of self, of melancholy, of longing, and of loss. An arranged collection of selections from a wider, ongoing, body of works, the anthology comprises six pieces, ranging from two to seven minutes in length; each is a discrete work in its own right, and a potential component of other overlapping or embedded anthologies. These are small works: made for one person, and offered to anyone else who cares to appreciate them. Though they touch on themes as grand as life and death, each begins as a blip in the banal &lrquo;” a slight emotional shift &lrquo;” noticed, caught and held to my attention a little longer than I ordinarily would: a touch of sadness, for example, on opening a box of used buttons and zippers; of mean-spiritedness directed at two hummingbirds; of the same slight unease every time I steer to keep away from the remnants of a place I used to play. Aesthetic and formal strategies vary according to the needs of each piece, on the whole favouring simplicity, understatement, and frugality of means, with&lrquo;”in elegy to my mother’s former talents&lrquo;”an emphasis on the art of making do.

The anthology is the outcome of a method designed to require little to no fundraising, and to accommodate a more heuristic approach to making work than the conventional development/production/post-production/distribution model permits. I did not at the outset propose a work; I proposed to engage in a daily practice of writing, shooting and/or editing, while concurrently caring for my mother, paying attention to small movements of daily life, and noting any transformations in my thinking. I promised to draw from that practice a number of works. Flipping the proposal to budget relationship on its head, I set myself a limit of fifty dollars in material costs per piece, assessed the resources I had on hand, and then developed ideas for works I could make with those resources. I had an old digital video camera, computer editing system and a low-tech telecine film to tape transfer machine, available to me at all times. I had occasional access to a Bolex, Super 8, and second digital video camera free of charge. I had several thousand feet of potentially X-ray damaged 16mm colour neg stock, but no extra money for processing and professional lab fees. I had a trunk full of outtakes from earlier films. Given fifty dollars to spend, what could I make? As a result of this method, I adopted a &lrquo;˜by any means available’ approach to materials, formats, and media, deliberately ignoring the historical categorization of works on the basis of originating media or final format. I favoured mini DV over more expensive formats, salvaged and recycled film over newly shot film, hand-processed over lab-developed film, low-tech over professional transfers. I incorporated not only film, video, and computer generated text and graphics, but also non-photographic digitized objects and artifacts.

I consider the work intermedia not only because it integrates materials originating on media usually categorized as separate but, more importantly, because I approach the transfer apparatus as a creative tool&lrquo;”on par with cameras, audio recorders and editing machine&lrquo;”and treat the discrepancies between media as elements of the language at my disposal. If I easily ignored historical divisions between media when assessing available resources, I found it difficult to deny their differences when working with them. The fact of film as “an endangered species” (Gunning 3) means that the material is laced with melancholy, impossible to ignore: it is like an extra layer of the emulsion, something I had to work with, whether I wanted to or not, whenever working with film. I was eager to take advantage of the economics of home-based, non-professional digital technologies; the low cost of mini DV made it particularly well suited to the shoot-now develop-later process I had embarked on. I remained wary, however, of the rhetoric of technological progress, and did not want to forgo entirely the tactility of film, nor its special relationship to loss. Instead of resigning myself to one or the other media, I chose to play them off each other. I became particularly attentive to the discrepancies between analogue and digital images, and especially their different relationship to their eventual mortality&lrquo;”one through decay, the other through obsolescence. Sharing the attitudes that Tom Gunning (borrowing a term from Deleuze and Guattari’s study of Kafka) associates with a &lrquo;˜minor cinema’ movement in late eighties avant-garde film, the anthology “forswears aspiration to mastery,” consciously adopts a position outside the conventional languages of mainstream cinema, celebrates its marginal identity, and bears its affection for the limitations of unprofessional materials, and do-it-yourself production technologies, on its sleeve (Gunning 2-3). In its defiant lack of pretension, its refusal to dismiss the ordinary and the domestic as irrelevant (MacDonald 232-233), and its de-emphasis of technical mastery, it is also in line with a largely unheralded strain of experimental films by women that Scott MacDonald suggests can be traced, in North America, back to the works of Marie Menken (210-215).

Situated at the confluence of a myriad influences, the anthology resists description in terms of traditional genre distinctions. It borrows techniques, concerns and materials from different strands of both experimental and independent documentary film and video, sharing with the more unsettling works of each, a tendency to speak through the formulation of relationships between different elements of cinematic language. Positing this tendency as the distinguishing characteristic of the poetic in cinema, the anthology aims to speak through relationships formulated between different material elements, between different times, sites and stages of production, between the original and archival status of its materials, between the themes of its component parts, and between its different formats, manners and modes of distribution and exhibition. It carries also through to these extended aspects of the work its defiant lack of pretension, its affection for limitations, and its mistrust of the &lrquo;˜masterwork.’

The anthology currently exists as two different master versions of itself. It is a thirty-minute series of works, mastered to video tape; it is a sequentially organized set of the same six works, mastered as a digital file, for distribution as a DVD. The two versions share the same content and the same sequential structure. The set version, however, is more open to a partial, selective, intermittent, reiterative and/or re-ordered experience of its component parts&lrquo;”by virtue of its simple, now standard, button interface. The set version also takes the form of a catalogue of works when the DVD is accompanied by an invitation to programmers to select one or more individual works to screen either separately, in a context of their choice, or in combination, in a permutation of their choice.

This Time Last Year (2 min) is a portrait of loss, formed in the interplay of nested elisions. Confessions of a Compulsive Archivist (7 min) discovers the story of a pattern of attachments, by forming relationships between things. Parenthesis (4 min) is a piece I found lingering between my intentions, forming itself on the side. A Figure on the Ground (4 min) is a picture of my self in several inferences at once, and a cross-sectional ode to a few of my influences. Two Hummingbirds (7 min) is a picture of all that is not there in the picture: the shape of the discrepancy between caption and image. Two Unrelated Shots (5 min) is an ode to our imaginative and creative instincts; it is the outcome of a simple decision to make something. All articulate what they do by invoking the imagined fields of what is actually presented.

Pictures of Things That Aren’t There is both a single completed work, and a transmutable collection of works. Individual pieces can be re-combined to suit program time restrictions or curatorial proclivities, and can be finished to different formats for distribution across different media platforms and exhibition circuits. Several pieces of the anthology are currently in distribution as stand-alone works; some pieces may remain stand-alone works in theory only, proactively distributed only in the context of catalogues or compilation works. Any new combination or permutation of works, screened publicly or semi-publicly, in series, with a title and credit sequence particular to that series, I will consider a new work, to be included in future lists of works, and available to others on request.2 One thirteen-minute embedded compilation&lrquo;”a trilogy comprising This Missing You, Parenthesis, and Confessions of a Compulsive Archivist &lrquo;” screened in a few semi-public venues in 2004, and is on record as a finished work, Three Portraits, as of that year. I have two overlapping anthologies (selections from Pictures of Things That Aren’t There in combination with works not included the present anthology) currently in progress. I also have an eventual feature-length compilation in mind, that will encompass most of the above works, along with others lying outside the present anthology, including some more explicitly about my mother’s illness.

The works in Pictures of Things That Aren’t There are loosely tied together by the circumstances of their production: all were initiated over the two-year period when I was assisting with the care of my mother as she lived out her life with a progressively degenerative dementia. None, however, are explicitly about her illness, or about my experience of caring for her; they are expressions of transformations in my thinking arising from that experience. They are not the only works I made during that period, nor do they together draw the shape of the whole of that experience. Pictures of Things That Aren’t There is the belt, if you will, of an Orion I can now envision but not yet draw or name: a larger but similarly transmutable collection about my experience of my mother’s dementia, structured as a conversation between the narrative of my thinking, and the narrative of my eye, over the course of that two-year period. The present anthology&lrquo;”each of its works a meditation on the unnoticed daily workings of the mental capacity I believed my mother had lost&lrquo;”forms one shape within the shape of that experience.

Linked by their shared attention to the imagination, each piece is about something else as well. Most have several themes in play at once, overlapping with each other’s themes, and with still developing themes of the still developing larger work about my experience of my mother’s dementia. The dominant theme of one work often returns as a secondary note in the thematic chord of another. My need to take a poetic magnifying glass to the stuff of attachments and loss informs more than one piece, though not all. Several pieces within the anthology share, as secondary themes, the dominant thematic strands of works lying outside the current anthology. My changing understanding of what constitutes a sense of self in light of my mother’s losses is one of these. A fascination with the transmutability of form, inspired by the feeling of watching death in slow motion (or was it life in time lapse?) is a recurring, if usually almost latent, sub-theme. Many of the works are inflected by my thinking about the relationship between photography and loss, particularly in light of the advent of digital technologies. All are influenced by the challenge I had set myself&lrquo;”to articulate what I meant by the poetic, in relation to the cinematic. Furthermore, each in its own way echoes the theme of Notes Before a Deadline&lrquo;”the widest, ongoing, body of works from which they are drawn. Inspired by the desire to make things before it becomes too late to do so, Notes Before a Deadline is designed to remain unfinished for life, and to exist only by inference&lrquo;”as the form of the relationships between its various manifestations. It is a work essentially about its own making and unmaking.

For all its attention to loss, Pictures of Things That Aren’t There is, like a eulogy, as celebratory as it is mournful. The circumstances and method of its production allowed me to use the moving image as a means of paying attention: to the artistry of the mundane, and the often unnoticed poetry of human minds just going about the daily business of living. If my mother’s presence is missing from the centre of the anthology, it is nevertheless felt, implicitly, like mine, through the holds, shifts and turns in my attention&lrquo;”the way her way of looking at the world influenced my own.