Part of Winter 2008

New York-based artist T.J. Wilcox has crafted a number of lyrical, witty and poignant short films, quietly sublime little gems one and all. Screening tonight will be Garlands 1-6 (2003-5) and A Fair Tale (Extended Mix) (2007). The aptly named Garlands string together several self-contained vignettes composed of footage and stills both found and shot (on Super-8) by the artist himself, with each collage imprinted and guided by Wilcox’s narration. This narration takes the form of subtitles rather than speech (the films are silent), giving the films a hazy, dreamlike and often nostalgic quality. A Fair Tale contains one of Wilcox’s most memorable stories: a county fair interrupted by an unexpected visitor from the sky.

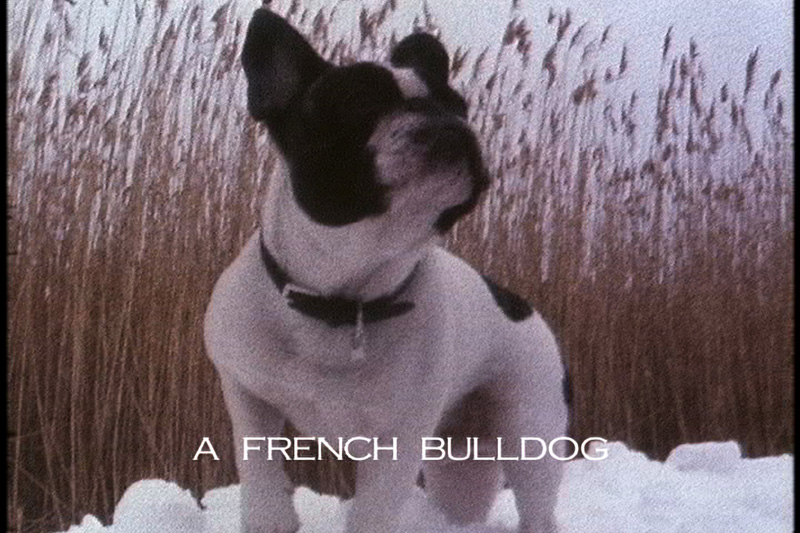

“T.J. Wilcox’s silent 16 mm films are collages of jumpy amateur material, historical images plucked from television, postcards, photographs and animation. They are obviously ‘hand made’; he films layer over layer, in grainy, blurred images and overexposed colours. He brings together figures from world history, individuals from his childhood, celebrities and aristocrats into a cinematic combination of fact, fiction and fantasy.” (Stedelijk Museum). In Wilcox’s delicate celluloid world, the Romanovs’ pet bulldog Ortino, Humpty Dumpty, a deaf house painter and a rodeo queen rub shoulders with stories of the origins of beekeeping and angora cats, the shape of the Long Island bus route, and the famous residents of Place Vendôme in Paris.

Programme Notes:

Programme:

Garlands 1-6 (2003-5, 48 min. 16mm on video)

A Fair Tale (Extended Mix) (2007, 9 min. 16mm)

New York-based artist TJ Wilcox has crafted a number of lyrical, witty and poignant short films, quietly sublime little gems one and all. The aptly named Garlands string together several self-contained vignettes composed of footage and stills both found and shot (on Super-8) by the artist himself, with each collage imprinted and guided by Wilcox’s narration. This narration takes the form of subtitles rather than speech (the films are silent), giving the films a hazy, dreamlike and often nostalgic quality. A Fair Tale contains one of Wilcox’s most memorable stories: a county fair interrupted by an unexpected visitor from the sky. In Wilcox’s delicate celluloid world, the Romanovs’ pet bulldog, Humpty Dumpty, a deaf house painter and a rodeo queen rub shoulders with stories of the origins of beekeeping and angora cats, the shape of the Long Island bus route, and the famous residents of Place Vendôme in Paris. (Jon Davies, Pleasure Dome)

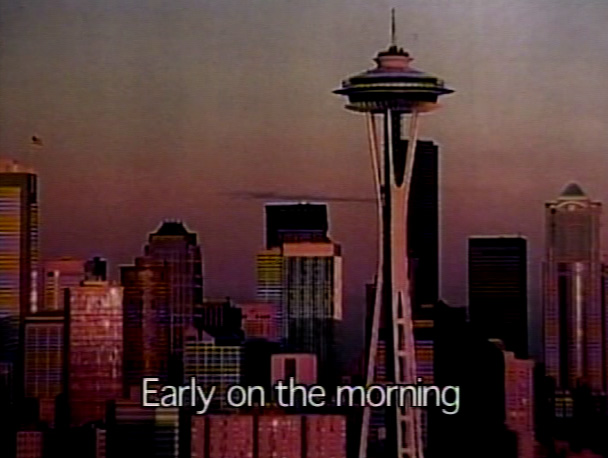

T.J. Wilcox was born in 1965 in Seattle. He lives and works in New York. He received a BFA from the School of Visual Arts in New York in 1989, and an MFA from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena in 1995. Since 1996 he has built up a modest oeuvre of about fifteen film works. Wilcox’s work has been seen in important art institutions such as the ICA in London, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Museum Ludwig in Cologne and the Tate Modern in London. In 2005 the British magazine After All devoted a special issue to his work. In the same year the American periodical Artforum proclaimed his Garland series “the best of 2005.” A hefty monograph devoted to Wilcox was brought out by the Swiss publisher JRP/Ringier in &lrquo;˜06.

T.J. Wilcox at Metro Pictures

Art in America, Oct. 2005 by Michael Amy

T.J. Wilcox is hooked on cinematic storytelling. Piecing together found footage, old photographs and original material, Wilcox shoots his films in 8mm and copies them onto video for digital editing (among other effects, they are artificially aged to look archaic). Transferred to 16mm, on reels containing one to three short films each, they alternate between stills and moving images in black and white, sepia tones and color, with subtitles that are of fundamental importance, tying the images together and giving the narratives added meaning.

Wilcox’s installations convey the impression of home movies shared with intimates. He projects them in the gallery onto standard-size freestanding screens. The whir of the machines, the changing tones, colors and degree of focus, the rhythmic progression of frames and the colloquial style of subtitles (with their occasional spelling errors) add greatly to the evocativeness of the whole. At Metro Pictures, Wilcox’s Garlands consisted of 16 films altogether (made in 2003 or 2005), projected from six 16mm machines. In one gallery, different films were played in the dark on four neighboring screens, allowing the viewer to slip from one narrative to another with a mere turn of the head, thereby adding sensations and layers of interpretation.

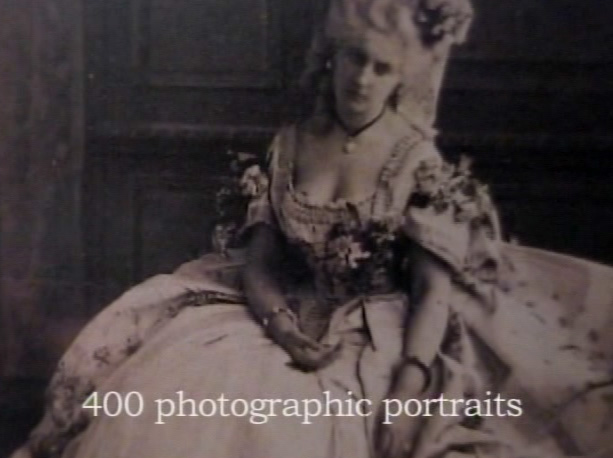

The focus of the lovely Garland 5 (2005) is the Place Vendôme in Paris. It consists of three segments about three famous people for whom the site had special significance. Shots of the Place alternate with images of the characters, and subtitles provide in-depth information. In the section on the 19th-century aristocrat and photographer Comtesse de Castiglione, Wilcox addresses the theme of physical beauty and its decline as manifested in the Comtesse’s behavior and self-portraiture. He touches upon solitude, illness and death in his portrayal of Frederic Chopin, and, in the segment about ambassador and socialite Pamela Harriman, he turns &lrquo;” with a good deal of humor &lrquo;” to sex, money, fame and political clout.

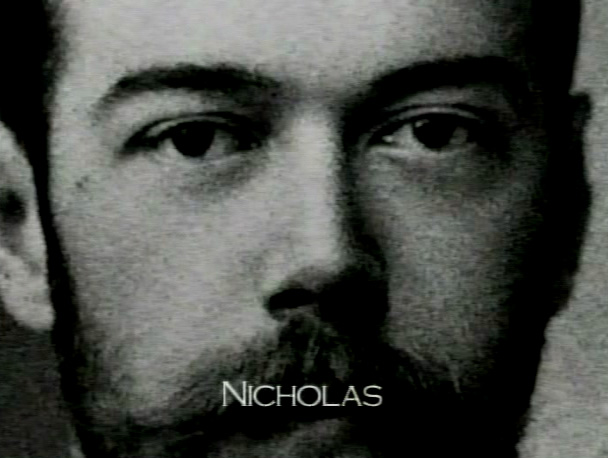

Another Garland, about the Romanovs, strings together vintage and original footage, along with many strange details, such as the princesses sewing jewels into their garments in preparation for their flight, and the execution of Tatiana’s bulldog along with the rest of the family. Here, the Bolshevik revolutionaries come off as embodiments of evil in a one-sided portrayal that verges on romantic adulation of the Russian royal family.

Wilcox understands our urge to make narrative sense of the bits and pieces of information we seize from the world around us. He can switch from candy-coated lyricism to blunt cynicism in the flash of an eye, and his most captivating stories are filled with surprises. Ultimately, they are tragic, addressing history and memory, desire and loss.

T.J. Wilcox; Metro Pictures, New York, USA

Frieze Magazine, Issue 90 (April 2005)

by Charles LaBelle

In the lobby of an old hospital on the outskirts of Marseille is a commemorative plaque that, roughly translated, reads: “Here the poet Arthur Rimbaud ended his terrestrial journey.” Below it a quote from his Illuminations (1886) adds the coda: “I have stretched ropes from steeple to steeple; garlands from window to window; golden chains from star to star, and I dance.”

The mise-en-scène could easily belong to a film by T.J. Wilcox – the marble floors with the late afternoon sunlight spilling across them, the spectral nurses, the plaque with its gold-leaf letters. It’s the type of moment one often experiences in a Wilcox film: a quizzical combination of romantic nostalgia and bemused wonderment at historical minutiae in which a recognition of loss leads to the wistful sense of everything being right in the universe. Like Rimbaud’s poems, shot through with sparkling imagery and a yearning for far-off places, Wilcox’s Garlands are often achingly beautiful and suffused with a palpable desire. Availing himself of a Symbolist palette of ambers, crimsons and greys, his images are patinaed but never dull. His camera moves (through a city, across a newspaper clipping) with a flâneur’s gait; leading the eye but aiming at the heart, visual pleasure in Wilcox’s work is always distinctly corporeal.

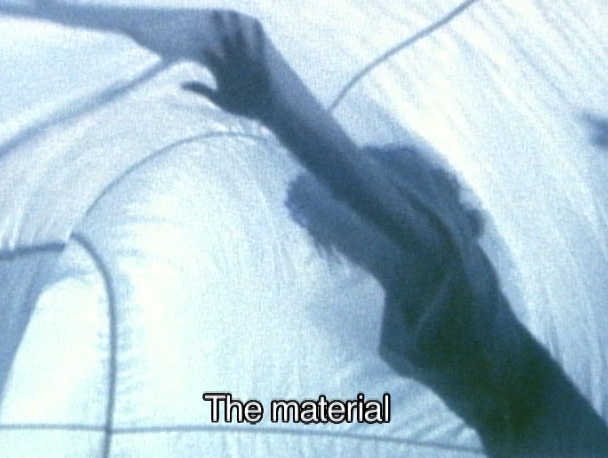

It’s rare these days to see evidence of the artist’s hand in a medium as cool (in the Marshall McLuhan sense of the term) as film or video, but Wilcox makes a distinctive, tactile impression in his films. Shot in low-tech Super 8, transferred and edited on video and then re-transferred and projected as 16mm, there’s a smudged, worked-over quality that underscores the base celluloid materiality of the film. This extends to the presentation of the films, which are projected onto old-style glass-beaded screens. In the gallery the screens and whirling projectors are as much a part of the viewer’s experience as the flickering storytelling, creating an atmosphere of intimacy that brings to mind a suburban family room of yesteryear, where home movies (and stag films) are shown amid small gatherings of family or friends.

The lovingly homespun feel of Wilcox’s work makes it seductive and immediately appealing. Richly textured, the films are chock-full of images of quaint, hand-crafted objects and melancholy mementoes of childhood innocence. Honeybees, kittens, sunsets, a flock of birds, are all given long and loving inspections. Overshadowed by a rueful black humour, they possess a hobbyist’s attention to detail and reflect an affinity for poignant tales of human aspiration and folly. Over the past eight years Wilcox has populated his narratives with a cast of characters worthy of a History Channel All-Star Game: Marie Antoinette, the Romanovs, Casanova, Marlene Dietrich, the First Emperor of China, Chopin and Ara Trip have all made their way into one film or another. His works run the gamut from the glamorous to the everyday: Garland 5 (2005) recounts the unrelated but somehow parallel biographies of the Countess de Castiglione and the American socialite, paramour and ambassador to France, Pamela Digby Churchill Harriman; Garland 4 (2005), by contrast, lingers over a hometown girl rodeo, an overdecorated Christmas tree and a finger tracing over wet paint the words “I have never forgotten.”

Wilcox has a knack for making history personal and small-scale, owing partly to the spare poetic texts that subtitle the films. Often combining first-person anecdotes with such genres as the travelogue, newsreel, children’s show, biopic, nature programme and experimental film (pioneers such as Stan Brakhage, Jack Smith and Jean Painlevé come immediately to mind), Wilcox’s filmic universe is a shifting, layered affair in which all things great and small are deemed equally worthy of our attention. More significantly, there’s an underlying cosmology at the heart of his entire project that probes the ways in which all these isolated things, people and places (both past, present and future) are joined.

Which brings me back to Rimbaud and Marseille – the setting for Stephan Tennant’s single unfinished novel Lascar. Tennant, an English dandy whose sensibility echoes Wilcox’s own, was the subject of an early Wilcox piece, Stephen Tennant Homage (1998). The antithesis of Rimbaud, who seemed unable to sit still, Tennant once famously spent four years in bed. Embodying a decadent penchant for indolence and reverie, he would surely have loved such Wilcox gems as Around the World in 80 Seconds (2003), which tours the globe via vintage postcards from its most famous cities. Experience, that most overrated of pursuits, is shunned in favour of expectant imagination and aesthetics. A potent distillation, Wilcox’s art offers a compelling case for staying at home, where one’s pleasures are ample and assured.

T.J. Wilcox; Metro Pictures Time Out New York, Issue 627 (October 4 – 10, 2007) by Anne Wehr

After seeing T.J. Wilcox’s show, I found myself thinking about those old Blackglama ads of various high- and low-cultural grand dames vamping in mink coats under the slogan, “What Becomes a Legend Most?” No fur to be found here (with one scandalous exception; more on that momentarily), but like the creators of that campaign, Wilcox is a seasoned pro when it comes to co-opting pop and historic icons to his own appealing ends.

The works here don’t cover new stylistic ground from his 2005 film suite Garlands, but if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it: Wilcox is a magpie storyteller whose romantic fascination with the past is infectious, and this sure-footed exhibition nicely showcases his dovetailing of original and appropriated material. A Fair Tale (Extended Mix) merges three works into one 16mm film. The title piece, a first-person narrative of a childhood journey to a county fair, is followed by The Jerry Hall Story, which at just over one minute long may qualify as the shortest biopic ever made. Lastly, there’s the tragic tale of the fin de siècle assassination of Austrian empress and horsewoman Sissi, wife of Franz Joseph I. There are also several large-scale ink-jet prints with vibrant watercolor touch-ups relating to each segment.

Innocence (and the loss of it) is an undercurrent, most palpably in Jackie on Skorpios, a video about the former First Lady’s fall from grace after the whole world saw her hoo-ha in some paparazzi sunbathing photos&lrquo;”the most famous of which Wilcox enlarges into a grainy life-size collage. Remarkably, the image still shocks even as it recalls a gentler era than our own. Now that’s full-frontal nostalgia.

Stedelijk Museum T.J. Wilcox – A Fair Tale & Garland One (January 26 – March 4, 2007)

What do Marie Antoinette, the bulldog of the Romanov family and the Roman Emperor Hadrian have to do with one another? They are all characters in films by the American artist T.J. Wilcox, a typical story-teller. Wilcox guides his visual narratives by the subtitles. There is generally no direct or unambiguous story line; rather, he creates an open relationship between the images and titles. This in turn opens up space for associations; the viewer’s own imagination is spurred into action.

T.J. Wilcox’s silent 16mm films are collages of jumpy amateur material, historical images plucked from television, post cards, photographs and animation. They are obviously “hand made,” sometimes frame by frame, without the intervention of a professional film crew. Wilcox shoots his own material on super-8, manipulates it digitally, and then transfers the end result to 16mm film stock. He was trained as a painter, a fact that can clearly be seen. He films layer over layer, in grainy, blurred images and overexposed colours. He brings together figures from world history, individuals from his childhood, celebrities and aristocrats into a cinematic combination of fact, fiction and fantasy which involuntarily draws the viewer along. In his work subjective history is mixed, as it were, with the reality of the news bulletin.

Garland 1 is one film from a series of six. In the films personal memories and stories surrounding historical figures that Wilcox has reshaped for his own purposes are loosely strung together like a garland. In Garland 1 we first see shaky, hand-held camera images of vague landscapes and snapshots from a family album: an elegy for the artist’s deceased stepmother. This is followed by the story of the slaughter of the Romanovs, the last Russian czar and his family, a mix of historic photographs and documentary images, some staged. The film ends with a bizarre fraise des bois animation. In it tiny characters guard a strawberry plant, which finally displays its red fruit.

The title A Fair Tale is an allusion to “fairy tale,” and literally means a carnival story. In it the artist tells about an excursion to a town fair with his parents and their “hippie friends” in 1972. The then seven-year-old narrator is overwhelmed by the attractions: the Ferris wheel, the pig race, and a rain dance by “Native Americans.” In the middle of the performance a parachute jumper unexpectedly lands in the fair. Gigantic clouds of parachute silk descend over the spectators. The little boy panics as he tries to find his way out from under the cloth. Before anything untoward happens he is lifted out of the billowing silk by a self-controlled arm: the boy’s heroic rescuer is no one less than the Indian chief.