Fri., Dec. 6, 2019

7:30 – 10:00 pm

Small World Music Centre

180 Shaw St, Toronto, ON

$10 General admission

$5 Members rate

or PWYC!

Part of Fall 2019

In recent years, with the election of right-wing and fascist politicians around the world, the link between fascism and capitalism has become impossible to ignore. As profit overtakes happiness as the endeavour of humanity and austerity becomes the way of the land, the citizens of the modern nation have no choice but to go with the pack or get trampled in the process. Of course, since it was left to fester for so long, capitalism has reached its inevitable zenith, reaching that time that we have been warned about for decades, the age of late capitalism. Existing somewhere between apocalypse and parody, the age of late capitalism has brought about dystopian ideals presented to its subjects as standard societal practices. No longer will people fight for their own rights, because their rights have been established as unrealistic, their fighting as criminal. Late capitalism is the current state of affairs. It cannot be stopped, unless people wake up to it, become aware of it. Perhaps the response from the art world could help that occur.

That is the idealistic background for Pleasure Dome’s Lost and Found in Late Capitalism, a response to this stage of late capitalism by using its own products. While capitalism continues to destroy our environment, wage wars on our people, and destroy our social fabric, this program will attempt to speak truth to power by speaking power’s language. This program consists of a series of short videos constructed from found footage, coming from a variety of formats, sources and levels of legality. These videos use footage from Hollywood films, business promotional videos, public domain artefacts and military footage to tell stories of life under the thumb of capitalism. It is through this re-appropriation of the products of capitalism that today’s artists can attempt to come to terms with the struggle of living under an unquestionable dictatorial system.

DOWNLOAD OUR PROGRAM ZINE with curatorial essay from Shahbaz Khayambashi, essay by Mason Wales, PLUS interviews. Additional editing by Katie Connell. Design by Rupali Morzaria.

Beyond Human, Pete Burkeet (Ohio, USA), 2018.

Mad as Hell, Emily Pelstring (Kingston, ON, CND) and Meg Remy (Toronto, ON, CND), 2017.

Gone Sale, Matt Meindl (USA), 2018.

Public Domain, Jason Britski (SK,CND), 2018.

A Feverish Fascination, Imogen Clendinning, (Windsor, ON, CND), 2018.

Music of Desire, Kristin Reeves (KY, USA), 2016.

Painting with the Man, Freya Björg Olafson (Toronto, ON, CND), 2017.

What is an Object, Stephanie Deumer (NY, USA) 2015.

Maelstroms, Lana Z Caplan (CA, USA), 2015.

Flat Pyramid, Kevin Doherty (NY, USA), 2017.

Curated by Shahbaz Khayambashi, Co-Chair, Pleasure Dome.

Sponsored co-presentation with the Department of Cinema & Media Arts, School of the Arts, Media, Performance & Design.

Interviews

Beyond Human, Pete Burkeet (Ohio, USA), 2018. 9:51 min.

PD: Heaven’s Gate has been a topic of renewed popular and academic interest in recent years. Certainly, the group’s engagement with the internet and interest in fusing science fiction with theology lends itself to a post-internet aesthetic. It’s easy to fetishize or reduce the iconography of a group like this, but your work manages to pick up on what’s fascinating about Heaven’s Gate while not falling into tropes. What does the experimental or non-narrative lend to telling stories about or representing cults or new religious movements (NRMs)?

PB: I have been fascinated by Heaven’s Gate for a long time because of their aesthetics. They called their bodies vehicles, lived as genderless as they could, and some went so far as to become castrated. In their ‘exit interviews’ which anyone can watch on YouTube they delivered their message in robes and custom patches resembling ones worn by astronauts, and their leader delivered his remarks in a polypropylene lawn chair with his image digitally repeated behind him to infinity. I suppose one could get caught in the kitsch of it all but I was more into sampling the energy and excitement they beamed about what awaited them after they ‘exited’. In Beyond Human I wanted to make something that could do justice to their ecstasy about leaving earth for a cosmic sci-fi journey.

Mad as Hell, Emily Pelstring and Meg Remy (Kingston, ON, CND), 2017. 3:00 min.

PD: Your piece uses an upbeat song and the sometimes comical expression of lip-syncing or hyperbolic choreography to effectively express rage. Can you speak a little bit more to the ways that either comedy or exaggeration is mobilized politically in your work?

EP + MR: Since this is a pop music video, its main function is to promote the song. At the same time, we were interested in maximizing the opportunity to deliver a serious message. Humour was a necessary tool, used to distribute the weight between a complex, urgent topic and a promotional act. Also, if we didn’t laugh, we would have only cried and gotten no work done.

Our critique is not limited to late capitalism, or to the military actions of the Obama administration, which the lyrics address. To talk about the recent and current costs of war, we mostly used footage from the 1940s-1970s. The age of the footage should tell us that what we are experiencing is not new. This ever-prevailing paradigm is already so extreme that nothing we could possibly do in a music video would be an exaggeration.

Gone Sale, Matt Meindl (USA), 2018. 5:00 min.

PD: The way that your work so effectively blends textured images of shopping and vintage signage with sinister music and voiceover reminded me a lot of Peter Strickland’s recent experimental department store horror film In Fabric. Can you speak to the ways that Gone

Sale evokes genre, despite its non-narrative format? What can horror uniquely evoke or express about late-stage capitalism?

MM: My film was influenced by the atmospheric elements of horror but rather than generating dread as a lead-up to a scare, I wanted Gone Sale to just sort of draw out those eerie feelings and marinate in them. Every shot is smeared with shadows and accented by heavy-duty-moody music. There’s humor mixed in too but the concept seemed compatible with horror because driving past a dead mall doesn’t feel much different to me than driving past a haunted house. It’s creepy. You have to look. You wonder what’s inside. I always think of a line from Zora Neale Hurston’s Dust Tracks on a Road that’s something like, “Nothing is so desolate as a place where life has been and gone.”

I’m also influenced by the way that we experience horror when we’re young, which I think is very impressionistic; it’s less about what happens in a movie and more about how it all feels and how it heats up your imagination. I like non-narrative experimental horror because I think it gets close to replicating that kind of viewing experience. I’m thinking Mike Olenick’s Red Luck here or a lot of Guy Maddin’s work.

It’s interesting to me that the shopping mall board game featured in Gone Sale was marketed to a generation that grew up and entered the workforce during a financial crisis and recession. The object of the game (get money and buy all the things woo!) didn’t seem all that weird for kids in the early ’90s but now feels totally absurd. And maybe horror is in a unique position to underscore the mounting absurdities of our foundering economic system. Half the filmmaker’s work is done–––I’m already scared.

Public Domain, Jason Britski (SK,CND), 2018. 4:33 min.

PD: Despite its archival footage, there’s something very contemporary about “Public Domain”. Can you speak to the ways that past and future converge in this work?

JB: With the film “Public Domain” I chose to use old archival footage that was all literally in the public domain. It is made with footage from approximately 1950-70, but it was always the goal to give it a more contemporary feel.

The old footage is very interesting in its own right, but I thought that with the counterpoint of the sound design that I could inject some of the tension that has crept into the political landscape in recent years.

To make a subtle statement about what is happening in the turbulent times we seem to have found ourselves in presently. I thought that it fit the scenario unfolding in America right now to show images that harkens back to a time that is being held up by many as the “good old days”, and to try and incorporate that sense of disruption, division, and anger through the relationship of the sound to the image.

The past and future do converge in many different ways in the juxtaposition of the audio and the imagery creating tension, humour, and hopefully introspection.

A Feverish Fascination, Imogen Wilson (Windsor, ON, CND), 2018. 20:00 min.

PD: Even from the title alone, we know that “A Feverish Fascination” is going to strongly evoke the body. Of course, the way you intercut found footage and layer sounds is incredibly visceral but I’m curious if you can comment more about the title of the work? Why are ‘fever’ and ‘fascination’ important descriptors of the spectator’s reception of this piece?

IM: When I made Fascination I was thinking about guilt and shame, the allure of watching acts of violence and consumer’s capitalist preferences in crisp and life-like images. To make something grossly abstracted felt like resistance to this better-than-real-life image perfection.

I chose the title because I wanted to reference the kinds of cliché ‘baser instincts’ that are often represented in popular media and entertainment. In my video, I’m interrogating the role of the observer, the watcher— I wanted to think critically about how violence and sexuality in media can affect our perception of reality. This fascination with the moving image seems feverish; once you dive in things begin to repeat themselves and become more powerful.

Throughout the 20-minute film, patterns begin to emerge. I hope that the viewer is compelled to look for consistencies, and later, the eventual disintegration of any formula. These patterns and smaller narratives are at first a like cheeky and dated, but as the images become more foreboding or violent the image abstracts completely. To take a piece of film work, re-examine it and abstract it is to take control of that image and the power it imbues. I give the viewer a small glimpse into what they are seeing, but in A Feverish Fascination the appropriator is in the driver’s seat.

Music of Desire, Kristin Reeves (KY, USA), 2016. 8:00 min.

PD: You suggest that you were excited and terrified of finding your own image in a medical archive during your research. Meanwhile, the images in your video are medical images of people in what could be called private moments. In your work and more broadly, what are the tensions between medical academia and privacy?

KR: I was photographed for pediatric research and unexpectedly found the images while alone in an examination room. It was me but also not. I was abstracted material and it was shocking. Medical images became personal because of this experience. Though I never discovered published images of myself specifically, I have found moments in medical/hygiene/educational media that felt like my own experience: intimate, real, and private turned institutional, voyeuristic, and performative.

Media cadaver is how I describe the educational materials I’ve been using. I think of my process as reanimation. Sometimes media bodies need to be reworked to understand/examine their pre-mortem use and other times I am conducting my own aggressive experimentation on them, afterward prescribing media therapy or education on the bodies within my films using pop songs and art tools. In Music of Desire video synthesizers model brain signal overload, the source materials point to sexual dysfunction which is frequently a symptom of trauma. The clinic and the art world deal with intimate human experience. I’m interested in where these histories and objectives cross paths.

The pediatric research I was a subject of (stature/growth) was used to loosen the interpretation of bio-ethical laws created to protect vulnerable bodies from exploitation. Part of my intention in using archival images was to avoid creating research subjects for my own use while criticizing for-profit bio-medical industry that recruits subjects as bio-capital. But I realized that the ethical concerns that I had regarding the use of vulnerable bodies could apply to found media.

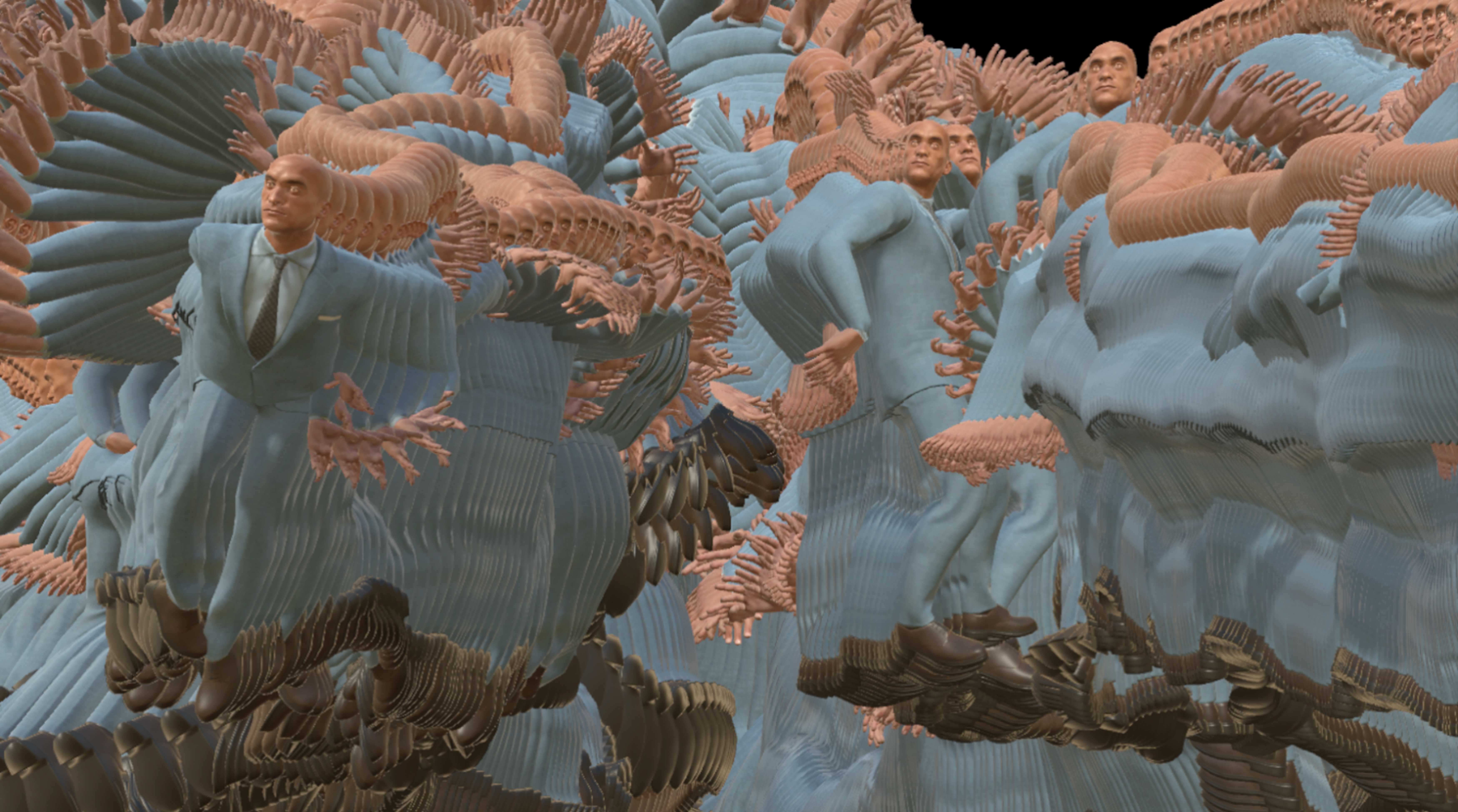

Painting with the Man, Freya Björg Olafson (Toronto, ON, CND), 2017. 3:37 min.

PD: You say that this work was inspired by Yves Klein’s Anthropometrie series, which employed nude women as living paintbrushes, in a classic bit of mid-century misogyny. Meanwhile, your work, painting with THE man, interestingly employs a man in a suit. Can you speak more to this “the man” designation and the dressing up of your paintbrush?

FO: Well, truth is I made the work before drawing a link to Klein’s series – the digital paint trails happened through an error when I was using the Unity game development software. After I screen captured the footage, Klein’s series came to mind as a clear reference in history – from female flesh imprinting on canvas to a digital representation of a male tracing the shape with blue pixels on a digital canvas. Through motion-capture techniques, anyone can use their movement data to embody and animate a digital representation of any figure. For ‘Painting With The Man’ I selected a 3D image of a man in a suit – which might signify a bureaucrat, a diplomat, an executive, a leader, or even the artist, Yves Klein. The avatar would elicit a closer connection to Klein if it was wearing a bow tie like the original formal suit Klein wore during the live painting. The avatar’s suit, however, is close in color to Klein blue. Whereas Klein animated nude women as human paintbrushes, I animated a 3D image of a man through motion capture which allowed me to embody a classic image of power – a man in a suit.

A nude body can be interpreted as without power or autonomy however this interpretation does not align with the recall of an original female performer who indicated she felt empowered and respected as a collaborator in the work. My use of a dressed-up man in the suit disrupts the perception of power since I control, animate, and drive movement from within the hallow 3D mesh avatar. The suited figure performs two distinct dances I sourced from the internet – one from a young female and the other an older male. I recorded myself re-performing these dances and then applied that movement data to the male avatar. As well I added control for the avatar to rotate their dance 360° on the spot, which reveals the backside of the figure as it turns and subverts front-facing offensive / defensive or powerful body language. Rather than placing emphasis on ‘Painting With THE Man’ in the title, I propose emphasis on WITH the man. Engagement through motion capture enabled me to explore or subvert cultural expectations of expression of gender through movement – both binary dances are embodied when I animate each from within the male avatar.

What is an Object, Stephanie Deumer (NY, USA) 2015. 7:06 min.

PD: I am almost tempted to ask you to verbalize the answer to your own question, what is an object? However, I would be more curious to know about this divide between analogue and digital media that seems to be present in your work. You take objectifying analogue media and use digital manipulations to subjectify them. Is there something about digital media that you find inherently liberating?

SD: I don’t think digital media is inherently liberating, but I do think in the context of this video, digital media can be seen as more accessible than analogue. I have only ever viewed most of the found footage and reference imagery that is featured in the video through digital media, whether by way of digital photographs of paintings and sculptures, or digital reproductions of films. Because of the development and proliferation of digital media, I have been able to access and view works like Gerhard Richter’s painting, Betty (1988), for example, or Hitchcock’s film Vertigo (1958). However, with digital media allowing for these works to reach wider audiences and become more prolific, also comes the multiplication and reinforcement of their content: which is European, male-centric, heteronormative, and often discriminatory against women. In a world that is predominantly patriarchal, these works along with their views are perpetuated as the universal standard, in part because of digital media. On the other hand, digital media can allow for other views and lesser-known works to become seen more widely. It can also be easily manipulated to allow for critiques of its content and form. In my video, I am interested in directly engaging with and subverting not only the appropriated works themselves, which are analog media, but also the multiple material realities in which they exist and circulate. So while, to a certain extent, I am using digital manipulations to subjectify objectifying analogue media, I wouldn’t say that I consider digital media to be a utopian ideal.

Maelstroms, Lana Caplan (CA, USA), 2015. 7:30 min.

PD: The footage in Maelstroms ultimately amounts to surveillance footage on an international level. The end goal of surveillance is to keep the undesirable out and away from the eyes of the established citizenry. What role do you believe the omnipresence of surveillance and dataveillance plays in our day to day lives?

LC: In this century, a twisted and broad societal implementation of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon has been realized. His 18th-century design was a circular building, lined with backlit open door cells, under the threat of omnipresent surveillance from a central observation tower. The residents in the cells could always be seen and yet never see the inhabitant of the tower. Foucault called it “a design of subtle coercion for a society”. Today, the optical surveillance this architecture afforded has been replaced by omnipresent electronic eyes and data. And like in the Panopticon, the expectation of this surveillance has become an intrinsic component of everyone’s lives. We know that every keystroke we make on the Internet is recorded, all of our movements tracked by GPS in our phones, and cameras constantly watch us in public – retail stores, city intersections, public transit stations, and front doors. This scrutiny has become naturalized in our lives as surely as air or gravity. The ubiquity of surveillance allows people to assume the record of their activities are likely just lost blips in the torrent of noise of flowing streams of images and data – until your identity is stolen or you get arrested for belonging to a political group or your employer asks about your Facebook posts. And now the surveillance has doubled back, asking the watchers to watch themselves, reversing the point of view with body cams on police officers and whistleblowers releasing classified data. Bentham’s simpler notion of social control has run amok, caught in a crossfire of ubiquitous information, images, and data.

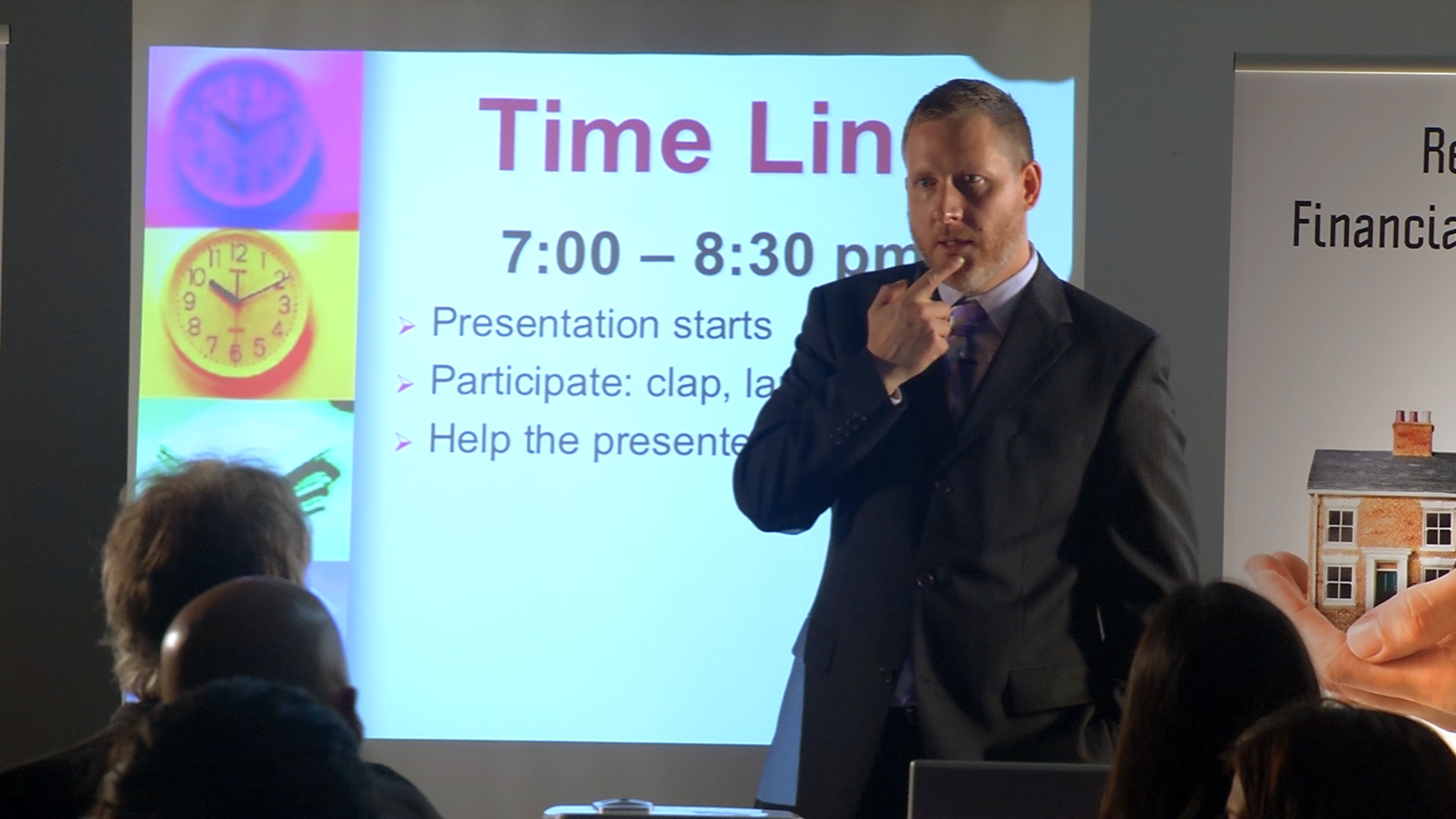

Flat Pyramid, Kevin Doherty (NY, USA), 2017. 11:30 min.

PD: How did you find the art in predatory behaviour?

KD: What I was most interested in was the response to predatory behaviour — people who oppose or fail to adhere to it. The tactics of a pyramid scheme, which “Flat pyramid” centers around, are more brash than artful and the materials they use to train others in their methods border on camp. Instead, it is their system that serves the most predatory purpose by hijacking the trust of individuals and their immediate communities to steal from them. Some work well within this system by replicating scenarios and reciting set scripts to reel people in. Others do not or flat out refuse to. Despite often tragic results, the fact that many cannot replicate this behaviour is the source of some hope, in that they might prove more resilient than the scheme itself.

Partners