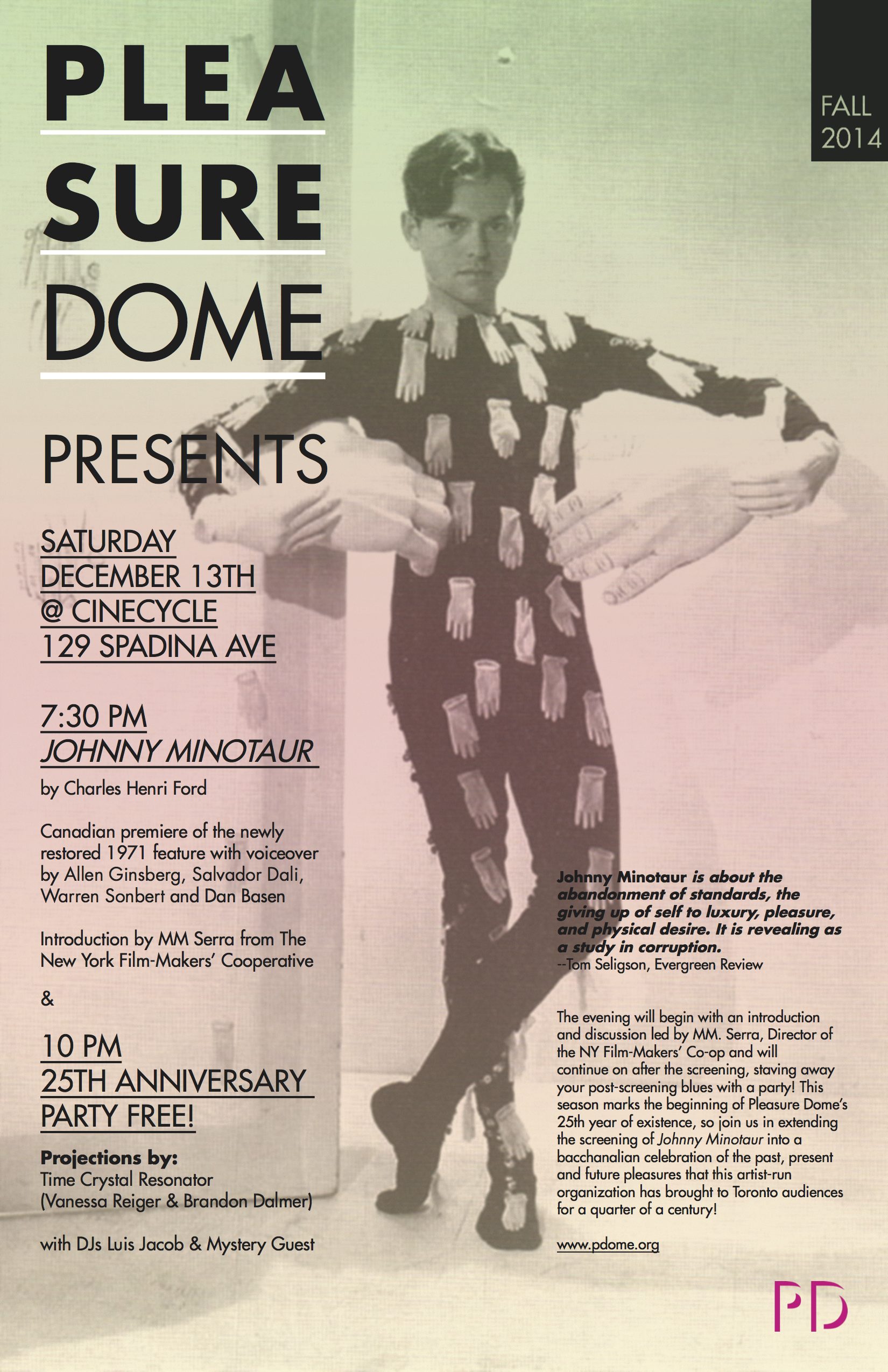

Saturday, December 13,

Screening 7:30 PM $8/ $5 Members + Students

with MM. Serra from the New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative, In Person

&

25th Anniversary Party, 10 PM Free!

Projections by Time Crystal Resonator (Vanessa Reiger & Brandon Dalmer)

with DJs Luis Jacob & Mystery Guest

@ CineCycle, 129 Spadina Ave.

Part of Fall 2014

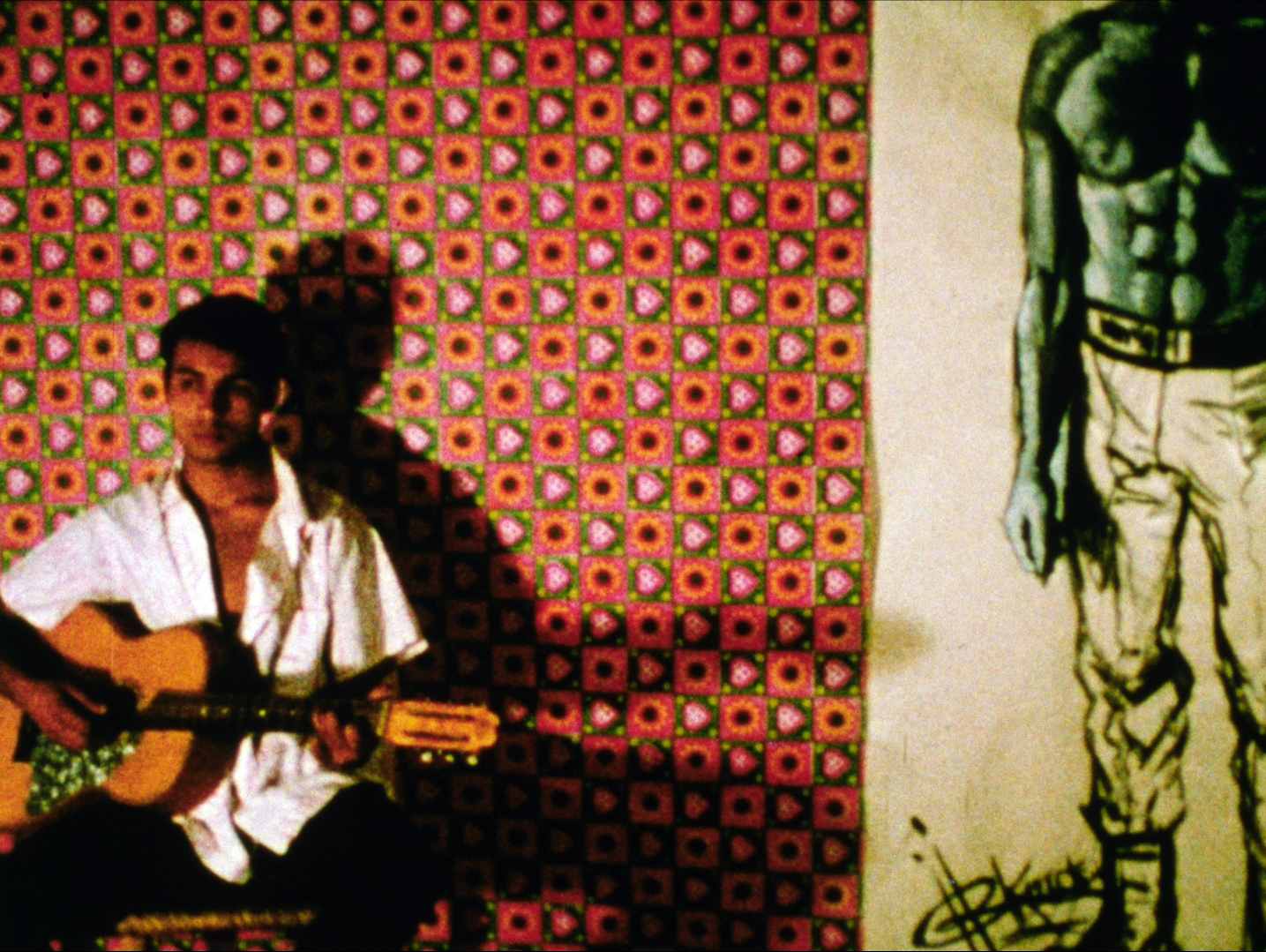

Surrealist poet and artist Charles Henri Ford’s 1971 film, Johnny Minotaur (80 min., 16mm, 1971) is a lyrical explosion of taboos: incest, intergenerational desire, pansexuality and autoeroticism are a few of the issues he grapples with through mythopoeic, sensual imagery, recitations of his diaries and a philosophical debate featuring an impressive narration by such artists as Salvador Dali, Allen Ginsberg, Warren Sonbert, Dan Basen and Lynne Tillman. Unseen for over two decades, The Film-Makers’ Cooperative & MOMA has restored Johnny Minotaur and resuscitated this classic of forgotten, queer cinema that belongs alongside the films of Kenneth Anger, Derek Jarman and Jean Genet.

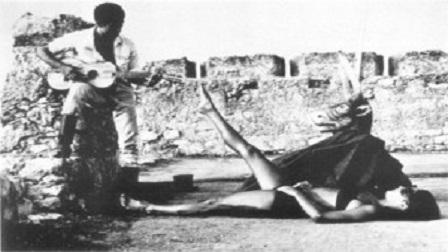

Shot during a soujourn on Crete, the film revives the Minotaur myth in modern times and includes appearances and footage by Allen Ginsberg, Warren Sonbert and other British and American artists and writers who had migrated to Crete during the 1960s. ‘Like his poetry the film is frank, American, homoerotic, mystically giddy and somewhat undervalued. The thin plot involves a middle-aged expatriate living in Crete, the pliancy of local youth, and a grasping niece who appears to threaten the dully domestic bliss…..As image poem, the film is inspired. A horny youth masturbates in a hollowed melon, a naked woman wraps and unwraps herself in the folds of a swinging hammock; three adolescents who could only have been dreamed of by Van Gloeden wash each other in an outdoor shower.”

Guy Trebay, Village Voice

“Johnny Minotaur is about the abandonment of standards, the giving up of self to luxury, pleasure, and physical desire. It is revealing as a study in corruption.”

–Tom Seligson, Evergreen Review No. 92, September 1971

The evening will begin with an introduction and discussion by MM. Serra, Director of the NY Film-Makers’ Coop and will continue on after the screening, leading the way to our 25th anniversary party! This season marks the beginning of Pleasure Dome’s 25th year of existence, so join us for a bacchanalian celebration of the past, present and future pleasures that this artist-run organization has brought to Toronto audiences for a quarter of a century!

Bios:

MM Serra is an experimental filmmaker, curator, author, and the Executive Director of Film-Makers’ Cooperative, the world’s oldest and largest archive of independent media. She teaches in the Media Studies program at the New School for Social Research on topics such as horror films, sex and gender as well as Avant-Garde and the Moving Image. Serra presented a lecture at the University Seminar on Cinema and Interdisciplinary Interpretation on “The New American Visions Series” in September 2012.

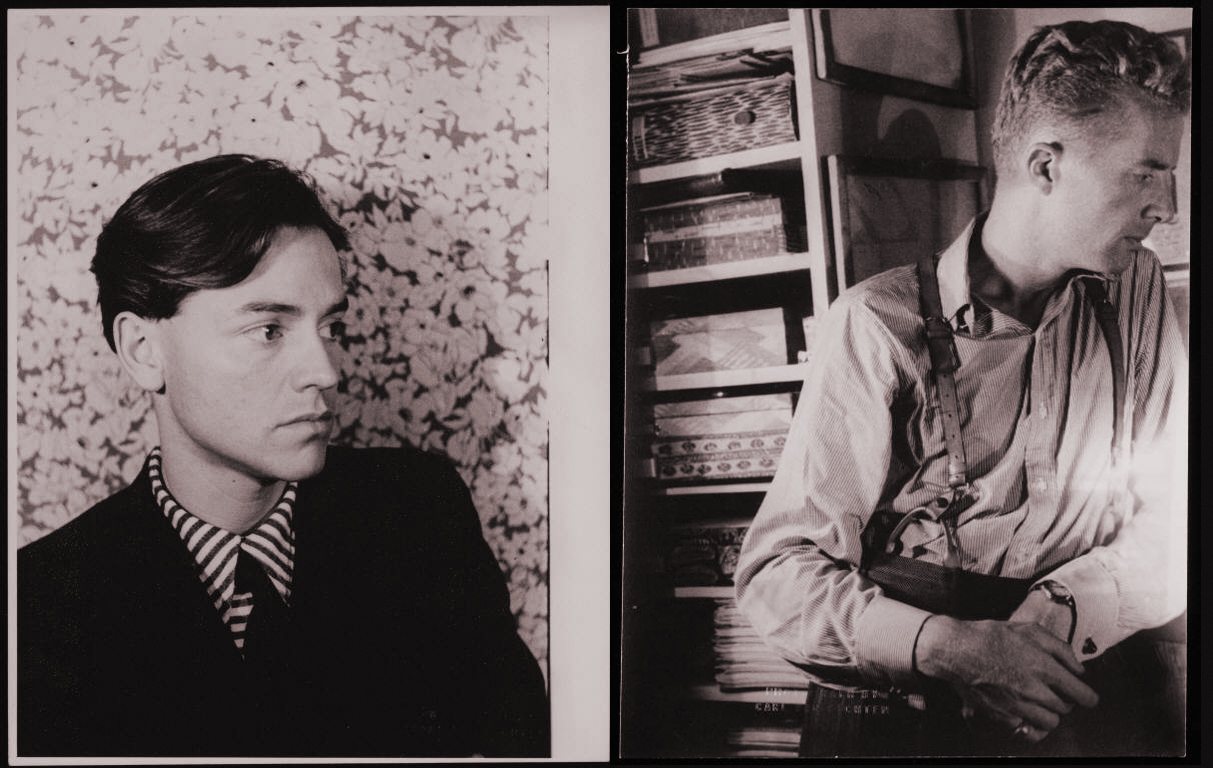

Charles Henri Ford was many things in addition to filmmaker. A pioneer of American surrealism, Ford’s creative activities as a poet, photographer, publisher and general bohemian bon vivant, spanned much of the last century and cultivated intimate connections and collaborations with legendary intellectual and artistic figures ranging from Gertrude Stein to Andy Warhol. Paralleling his artistic trajectory in the avant-garde, as an openly queer man, Ford’s life and work was also at the vanguard of mid-twentieth century sexual politics, and like his gay colleagues and contemporaries— Allen Ginsburg and Kenneth Anger, for example— Ford’s art fused his outsider sexual status with the vital underground sensibility of the poets, painters, and filmmakers with whom he associated.

Born in Mississippi in 1913, by the age of 16 the precocious Ford had quit school to found and edit his first magazine, Blues: A Magazine of New Rhythms, publishing work by American literary notables such as William Carlos Williams and Paul Bowles. By his early 20s, Ford had moved to Europe, finding a place in Stein’s coterie of American expatriate writers and artists in Paris. Through Stein’s circle, Ford met and began a passionate relationship with the Russian surrealist painter Pavel Tchelitchew. With the outbreak of the Second World War, Ford returned to New York with Tchelitchew, moving into the artistic and literary circle which included Orson Welles, George Balanchine and e e cummings, as well as occasional visitors such as Cecil Beaton and Salvador Dali.

Ford’s first full-length book of poems, The Garden of Disorder, with an introduction by William Carlos Williams, was published in 1938. In 1940 Ford again teamed up with Parker Tyler to start View magazine, which functioned as a major transatlantic conduit of the European avant-garde and published English translations of writings by André Breton, Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre along with work by visual artists like Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Max Ernst. He continued to write poetry: Poems for Painters was published by View editions in 1945, followed by The Half-Thoughts in 1947 and Sleep in a Nest of Flames in 1949, which included a foreword by Edith Sitwell, with whom he had by then been reconciled. He also edited The Mirror of Baudelaire (1942) and A Night with Jupiter and Other Fantastic Stories (1947), which contained two pieces by Henry Miller.

During his early years in Paris, Ford forged a life-long friendship with Parker Tyler, who would go on to be a critic and astute advocate of experimental film at Film Culture. Together, the two coauthored the experimental novel The Young and The Evil, a work widely regarded as landmark in queer literature for its sympathetic and non-judgmental portrayal of its gay protagonists. The Young and The Evil was based on their adventures in the high-camp homosexual underworld of Greenwich Village. Edith Sitwell described the book as “entirely without soul, like a dead fish stinking in hell”, and threw it into her fireplace, declaring that in earlier times she would have had Ford’s skin made into a bathmat. Ford envisaged her “fanning the flames with her skirts”. It was published in Paris but banned in Britain and America until the 1960s, though smuggled copies were given wide circulation in bohemian circles.

In 1952 Ford and Tchelitchew returned to Europe, where Ford embarked on a new career as a photographer and artist. An exhibition of his photographs, Thirty Images from Italy, was held at the ICA in London in 1955 and, a year later, he had his first one-man show of paintings and drawings in Paris; Jean Cocteau wrote the foreword to the catalogue. Ford’s turbulent relationship with Tchelitchew ended with the latter’s death in Rome in 1957. Ford returned to America five years later and was immediately taken up by a new generation of artists, including Andy Warhol and Robert Mapplethorpe. Ford took Warhol to “underground” movie screenings and introduced him to the film makers and poets Willard Maas, Marie Menken, and the young poet and silk-screen artist Gerard Malanga who would appear in several of Warhol’s films. He is credited with encouraging Andy Warhol to purchase his first 16mm Bolex camera, and would go on to sit for one of the famous Screen Tests shot at the Factory.

As a filmmaker in his own right, Ford’s first project was 1967’s Poem Posters, an experimental documentary of a 1965 exhibition of his brightly-colored surrealist collage work featuring camera work by luminaries of the underground film scene such as Marie Menken and Gregory Markopoulos. Ford’s second film was Johnny Minotaur. Lightly dressed in the trappings of the Greek myth of Theseus, Ariadne and the labyrinth of the titular Minotaur, the film combines surrealist symbol with erotic kitsch and is punctuated by moments of almost lyrical cinematic véretié. Johnny Minotaur’s film-within-a-film structure follows the poet/director Karolos (Chuzzer Miles) during the production of his film about the Minotaur myth. The border between Ford’s and Karolos’ films are porous, however, and the distinctions between the two-and between reality and the fantastic-are as hazy as the sun-drenched shores of Crete where the film was shot.

From the mid 1960s Ford began producing so-called “Prose Poems”—large, colourful collages that combined elements of poetry and pop art. During the last decades of Ford’s life, his companion was Indra Tamang, a Nepalese artist whom Ford met in Kathmandu in 1972, and with whom he collaborated on The Kathmandu Experience, an exhibition held in 1974 at the New York Cultural Center. Ford’s later collections of verse include Spare Parts (1966), Silver Flower Coo (1968), Om Krishna (1978), Secret Haiku (1982), Emblems of Arachne (1986), and Out of the Labyrinth (1991).

Charles Henri Ford died in Manhattan on September 27, 2002.

INTERVIEW with MM Serra on the U.S. premiere of Johnny Minotaur

Westword: What are your thoughts on the U.S. premiere of Johnny Minotaur?

MM Serra: It was a wonderful screening. I thought the preservation print looked gorgeous. The theater was beautiful. I’d never seen Johnny Minotaur projected so large. I saw it projected at the Museum of Modern Art in a small theater and projected in my office for selected curators to get shows, but this was the first time I’d screened it in public. I thought the projection was exquisite and the preservation was beautifully done. There were so many textures, the quality, the images, the sound, it was just lush and exquisite. The cinematography was beautiful and so emotional, and the sound actually carries the narrative.

The different voices on the soundtrack told the different stories: the Minotaur story, the diaries of Charles Henri Ford, the relationships, the difficulties of having intimacy whether it’s polymorphous, heteronormative or homosexual. You can have sexuality, but to get to intimacy is the most difficult. One of the audience members said to me that he felt that the film was about loneliness, and I felt that, too. Charles Henri Ford was talking about himself and how the search for identity in culture is a struggle. For him that was a lonely struggle.

I thought the audience was very informed and intelligent; I was surprised by how it was all-ages, from college students to older retired people. It was a very diverse audience. I thought Denver Film Society’s staff, the curators and the people working there were very knowledgeable, informed and articulate, and that helped with the screening as well.

Johnny Minotaur feels like a missing link in the history of queer cinema.

Its original premiere was a celebrity event. Andy Warhol was there; Viva was there; Taylor Meade was there. Barney Rosset wrote about it as a celebrity event in Evergreen Review. Barney Rosset helped change the laws of censorship when he brought I Am Curious Yellow to New York. He argued it was aesthetically educational, and that’s what changed the law. If a film had nudity, if it also had some redeeming social value or aesthetic content that was educational, it wasn’t porn. Barney Rosset wrote about Johnny Minotaur. It showed at Anthology Film Archives in 1972. In ’71, Jonas Mekas interviewed Charles Henri Ford about the film in Village Voice. In the ’80s, it showed at the Wooster Group. So it had screenings. It was written about, and it was talked about.

Eventually, it got damaged. It had sprocket damage. I had talked to Charles Henri Ford, and he left it at the Filmmakers Cooperative for us to preserve it. It took over a decade to get the funding and the cooperation with a major, absolutely major museum to do the work. We worked with one of the best preservationists.

I’m so glad I didn’t get one negative response at the Denver screening. One of the young college students, a woman, came over to me. She said she was excited to see it. It was a wonderful, amazing film and influenced her. I didn’t receive any negative comments. Not one from anyone. Not that there should be, because I think that the film itself is very poetic. It does have male nudity in it, but I think the audience is more informed by the Internet and nudity is on the Internet a lot. Charles Henri Ford himself said it was about autoeroticism, exhibitionism and polymorphous sexuality. It was erotic, and it wasn’t just homosexual. I though it had those aspects, too, but it also had the exquisite aspect of his nude niece. He filmed her in this hammock and she swings back and forth in the sunlight. It’s so radiant and beautiful and textured, and she’s beautiful.

That was another fascinating dimension. There’s this incestuous voyeurism. This movie is hitting on so many taboos that are very triggering to a contemporary audience.

I was just reading the Nancy Mitford book called Voltaire in Love. Voltaire was very close to his sister, and when he was older, in his fifties, he fell in love with his niece and had a relationship and spent the rest of his life living with her. That wasn’t considered scandalous at that time; I think that now it is. I think that some taboos at that particular time, before the French Revolution, were more acceptable.

Have you read Hollywood Babylon? Think about Charlie Chaplin falling in love with a movie star; she was nine, maybe even seven. He married her when she was thirteen or fourteen. I think that this idea that there is a marriageable age is something that’s more contemporary.

Talk about the historical differences between the time Charles Henri Ford was working on Johnny Minotaur and now?

Charles Henri Ford, as soon as he was a teenager, he left the South. I think that’s why he was able to have such a rich education in poetics and art history and why he had such a deep relationship to modernity. He was very informed by surrealism, by Picasso and Salvador Dali, because he actually knew them. It wasn’t that he was looking at pictures in a book. He was actually walking among them. Going to Paris was a really seminal part of his creation of his identity — knowing Duchamp. He’s published in the Penguin Edition of American Surrealist Poetry, so he identified strongly as a surrealist. Surrealism really breaks away from a lot of the bourgeois taboos and is really influenced by the unconscious mind. That was really present in the film.

Mekas, in his interview, talks with Charles Henri Ford: “Don’t you think the film within the film could be a cliché? It’s done so much. Charles Henri Ford said, “It’s been done for a thousand years and will keep being done, because it’s self-reflexive. It’s the ability to tell multiple stories.” That’s what he does in this film. It’s the story of the Minotaur and what the Minotaur means. It’s like you keep peeling away, and there are more and more layers to the story. I think the soundtrack is very important in telling and referring to these stories, myths and diaries.

I think it was a breakthrough that it showed in Denver. Several people talked about getting arrested; I don’t think that’s an issue. They’re so fearful. It’s xenophobia in a way. I’m not sure that’s the right word. There’s this fear factor. It showed, and nobody came charging through the door to arrest anyone. I don’t think there is anything in that film that isn’t on the Internet. It’s not like showing Salo; Salo is much worse. I mean, it’s painful to watch. I think there is something exquisite about Johnny Minotaur.