Part of Winter 2013

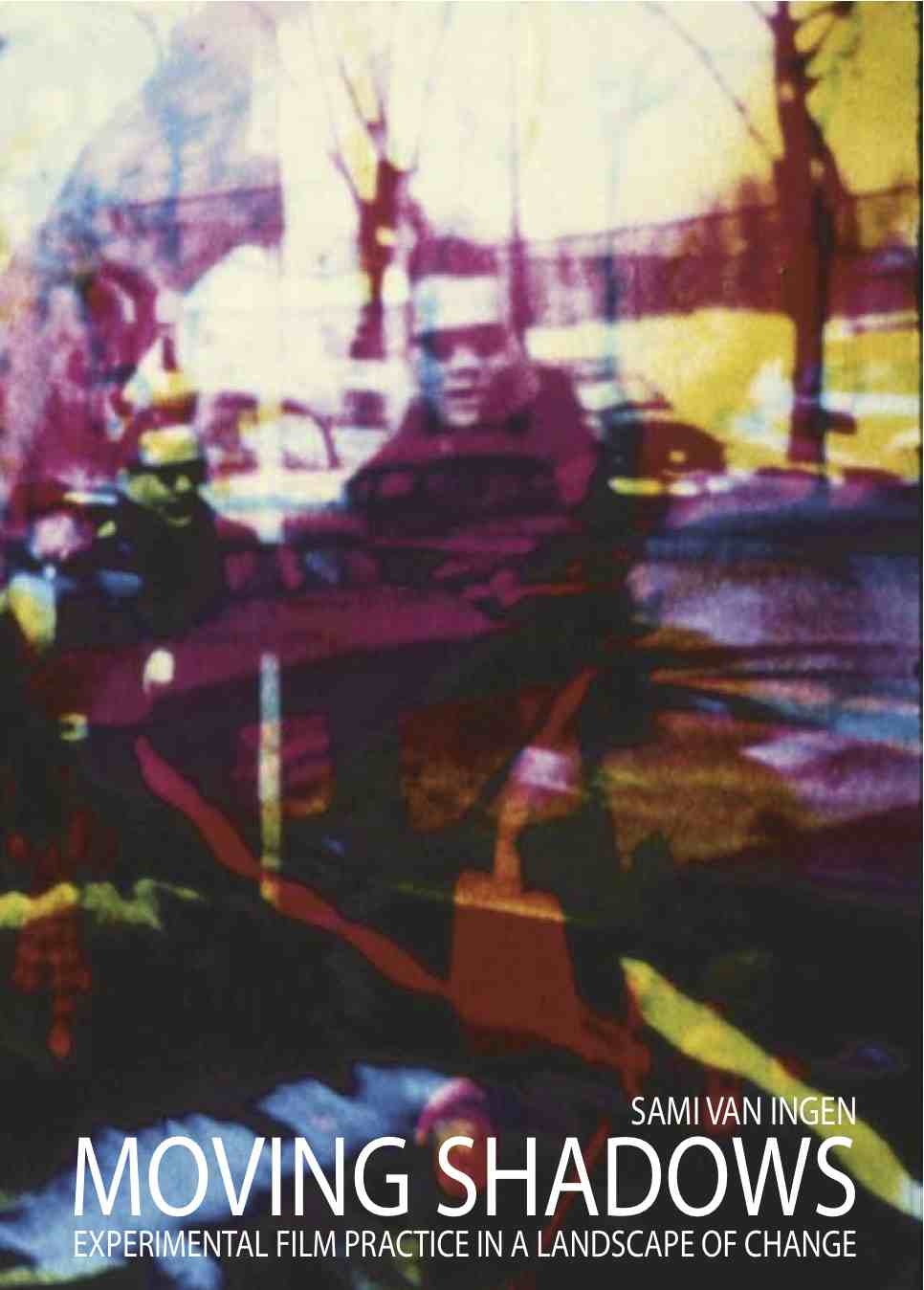

Join us for the launch of Sami van Ingen’s recent publication Moving Shadows: Experimental Film Practices in a Landscape of Change (Finnish Academy of Fine Arts, 155 pg., 2012, Helsinki). Following the reception Sami will introduce his curated program, Moving Shadows, a collection of works exploring the nuances of analogue film. The program is bookended by Peter Miller’s Projector Obscura, in which Miller has used the cinema projector as a camera, and Peter Tscherkassky´s Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine, in which the demons of celluloid are evokedby playing havoc with the bandits of Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Also featured are John Kneller’s brand new print of Separation, Bill Morrison’s sparkling 35mm print of Light Is Calling, John Price’s exceptional 35mm Gun / Play, Richard Reeves’ Element Of Light, and van Ingen’s most recent work, Hate.

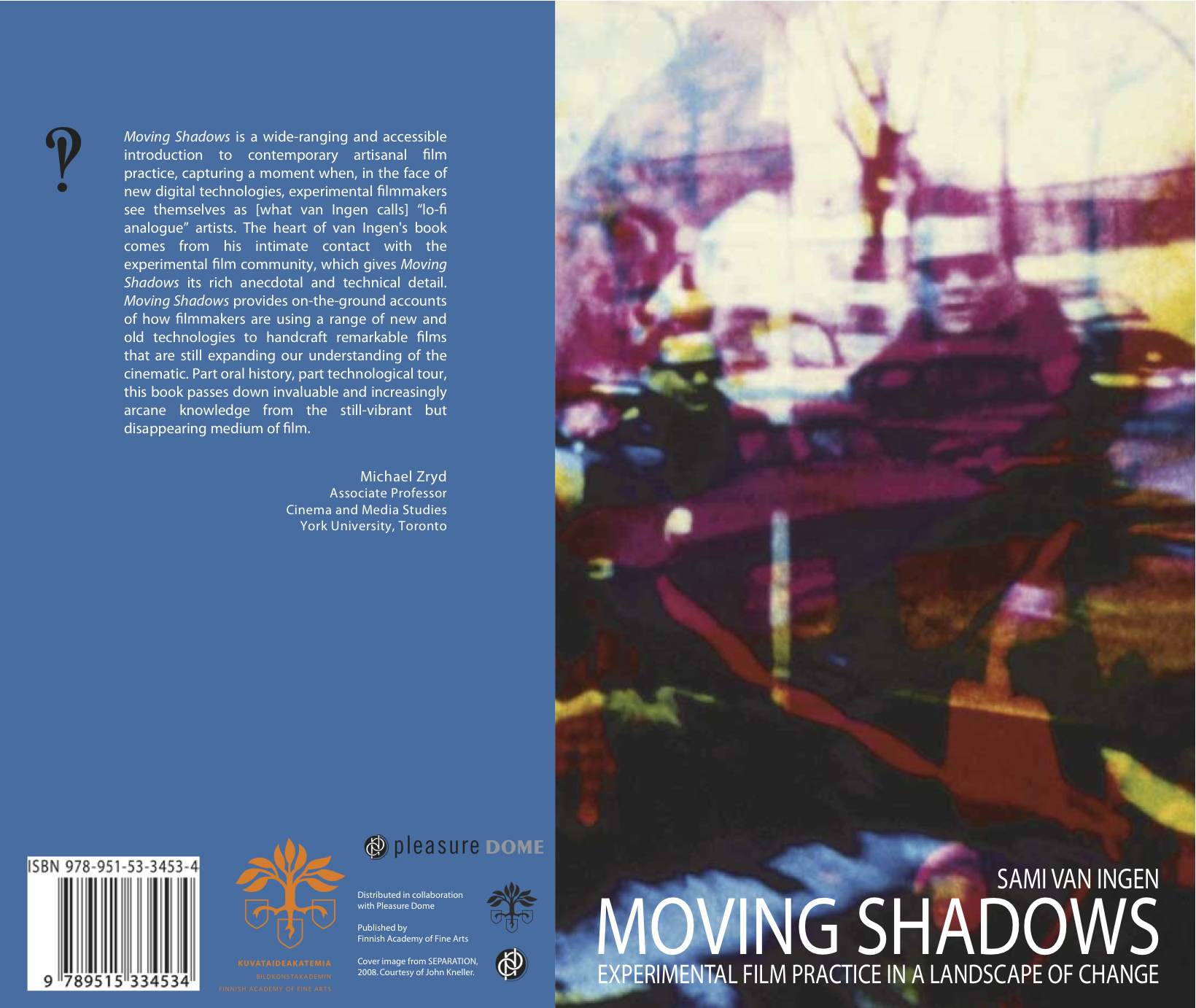

“Moving Shadows: Experimental Film Practices in a Landscape of Change is a wide-ranging and accessible introduction to contemporary artisanal film practice, capturing a moment when, in the face of new digital technologies, experimental filmmakers see themselves as [what van Ingen calls] “lo-fi analogue” artists. The heart of van Ingen’s book comes from his intimate contact with the experimental film community, which gives Moving Shadows its rich anecdotal and technical detail. Moving Shadows provides on-the-ground accounts of how filmmakers are using a range of new and old technologies to handcraft remarkable films that are still expanding our understanding of the cinematic. Part oral history, part technological tour, this book passes down invaluable and increasingly arcane knowledge from the still-vibrant but disappearing medium of film”. (Michael Zryd, Associate Professor, Cinema and Media Studies, York University, Toronto)

7pm Book Launch (Special launch price of $15 for Moving Shadows)

8 pm Screening

Programme:

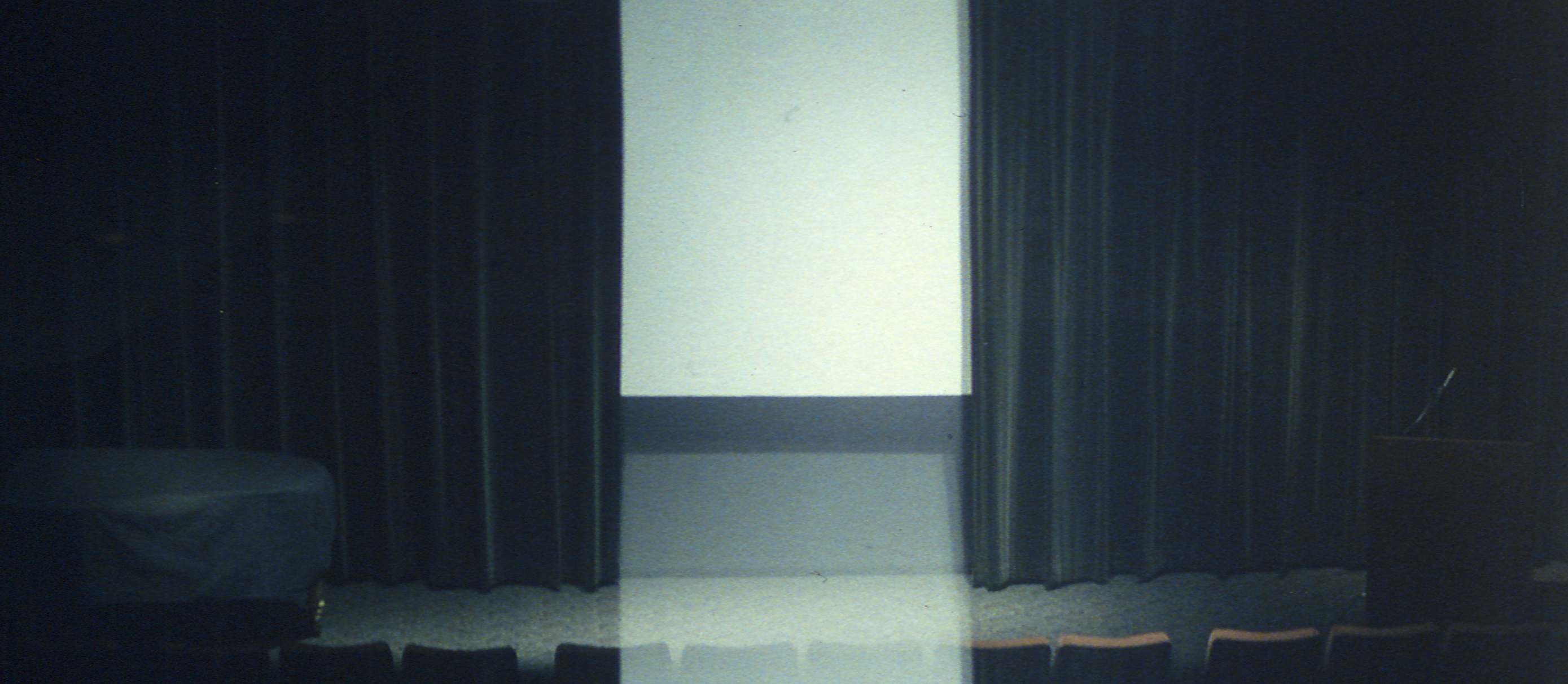

Projector Obscura (Peter Miller, 2005, 10 minutes, 35mm)

After the first or second shot, it becomes quite obvious what we are seeing pictorially and formally a series of cinema screens. Miller gives some light back the projector rather than simply expecting it to emit light. The significance of Projector Obscura is the way Miller has come up with a reversal of the cinematic process. Projector Obscura is a film projected like other films, but its images do not originate from the same place as other films: they are the product of the same apparatus through which we watch the film – the projector. We are watching the screen showing itself to us through the apparatus of cinema, a revelation appearing on a screen illuminated by the image of the screen. Miller’s film does not have the illusion of the “outside” that the cinema draws its illusionistic power from, but instead it creates a sort of cinematic travelogue of the cinema as a space and as a part of cinema’s landscape of illusion.

Separation (John Kneller, 2008, 9 minutes, 16mm)

In Kneller’s film Separation (2008), the tranquil mood captured in a home movie becomes disturbed by its colors separating into rhythms of discontent. The un-synching or dismantling of the film’s colors reveals what the image is made of, namely, densities and layers of colored pigments. Kneller’s action points to a similar layering in the image content: the apparently happy holiday scenes being made up of layers of presumptions of what happiness is.

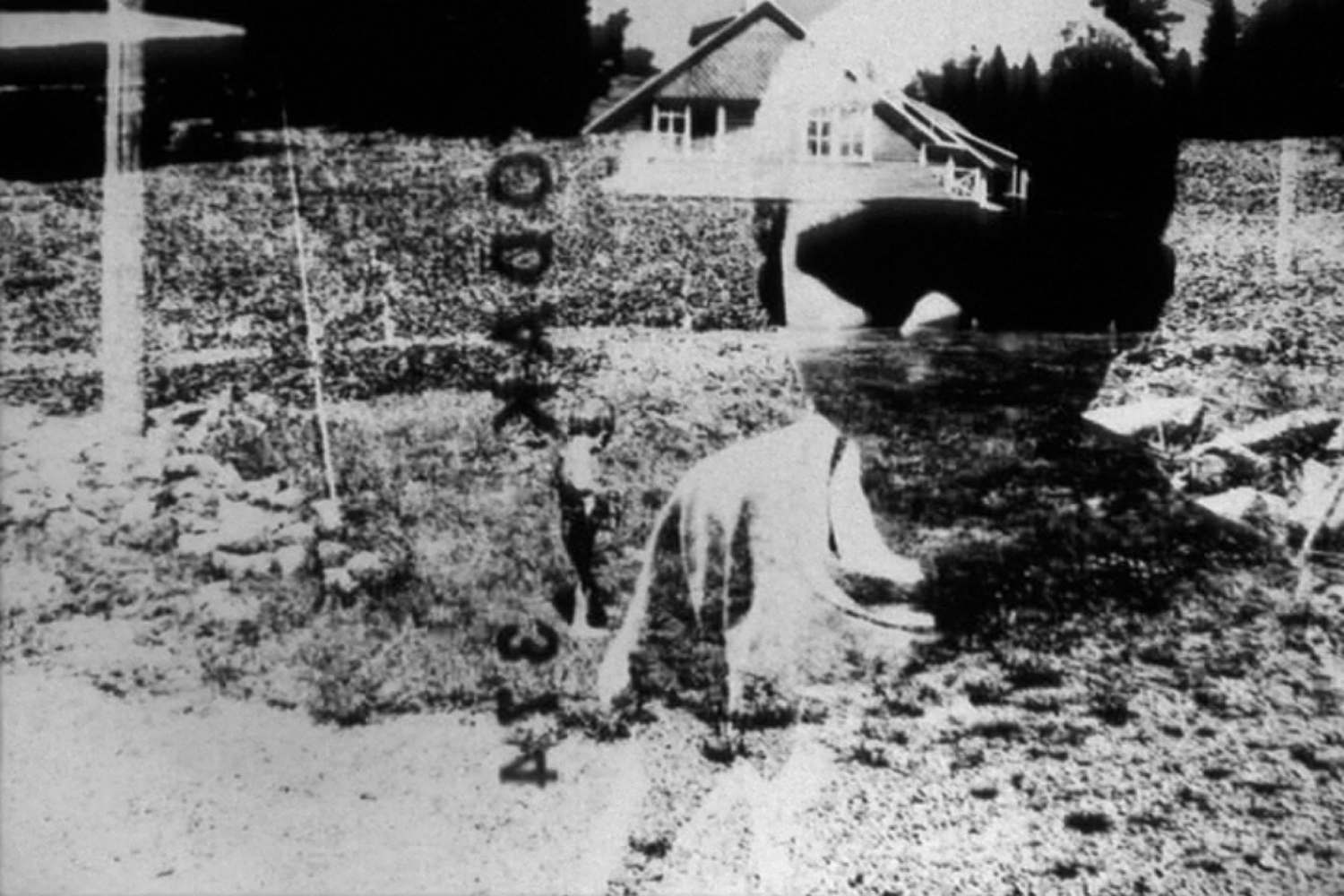

Exactly (Sami van Ingen, 2008, 8 minutes, 35 mm)

The starting point for the project was finding a 16mm roll of film that was visually unusual and initially appeared to be some kind of residue material from an experimental film project. Each image on the filmstrip reached over two frame lines and extended over the entire surface. I eventually discovered, in a technical film laboratory manual, that it was in fact a piece of slug -recycled film. The drama unfolds in slow motion and through the flutter of the images. The materiality of the recycling process, and the failure of this process to render the image “unusable” becomes central.

Light Is Calling (Bill Morrison, 2004, 8 minutes, 35mm)

Morrison re-edits badly damaged archive imagery in his exploration of the notions of decay and residue. The slowed down images with their wrinkled and distorted surfaces gradually reveal themselves. Scenes of soldiers on horseback and horse-drawn wagons in a decaying landscape have a haunting, return of- the-dead quality. Light Is Calling unfolds with a hypnotic rhythm and through continuous dissolves. Each original frame is repeated four times and superimposed with an adjacent frame, exposing the new mutilations in the emulsion: depictions of young men in uniforms metamorphosing into zombies, their uniforms bulging out of proportions; the faces of young women appearing as if from a leper colony. It is hard to identify what is happening, other than that we are immersed in an animated, but decaying picture book of Americana. It is as if one is seeing the nostalgia that the old images evoke turning sour. We are looking at the physical residue of film culture, the leftovers of the leftovers.

Gun / Play (John Price, 2006, 9 minutes, 35mm)

Price’s films are delicate observations about the world around him and are made with strong personal sensibility. They are somewhat like rough snapshots of the everyday, but seen through a gigantic monochrome and grainy loupe, that produces an intense sense of the present. We observe and share the world of the filmmaker through this process. The apparatus of cinema is always present in his works. The textures of processing and the use of high-contrast film stocks are only part of this presence, sometimes we can read fleeting messages intended for the eyes of the lab technicians only, that seems to point towards alternatives.

Element of Light (Richard Reeves, 2004, 4 minutes, 35 mm)

Richard Reeves’s Element of Light (2004) is a four and a half minute film spectacle of motion painting. Reeves’s intricate hand painted and scratched film plays with scale and particles: the small flakes of crumbling emulsion are magnified to a moving landscape of textures. Reeves has created a retina-caressing flow of colors out of virtually nothing – in many parts of the film he has only eroded some of the opaque film surface of black leader thus partly exposing bits of the colored layers that make up the base. So in a way the creation of the images in Element of Light is comparable to how a sculpture emerges from a piece of stone – not by adding but by subtraction. By using Cinemascope, the widescreen format developed for depicting grandiose landscape of the west, Reaves could be seen to have created an inward sculptural landscape of the film medium itself – the Monument Valley Mittens of Cinema.

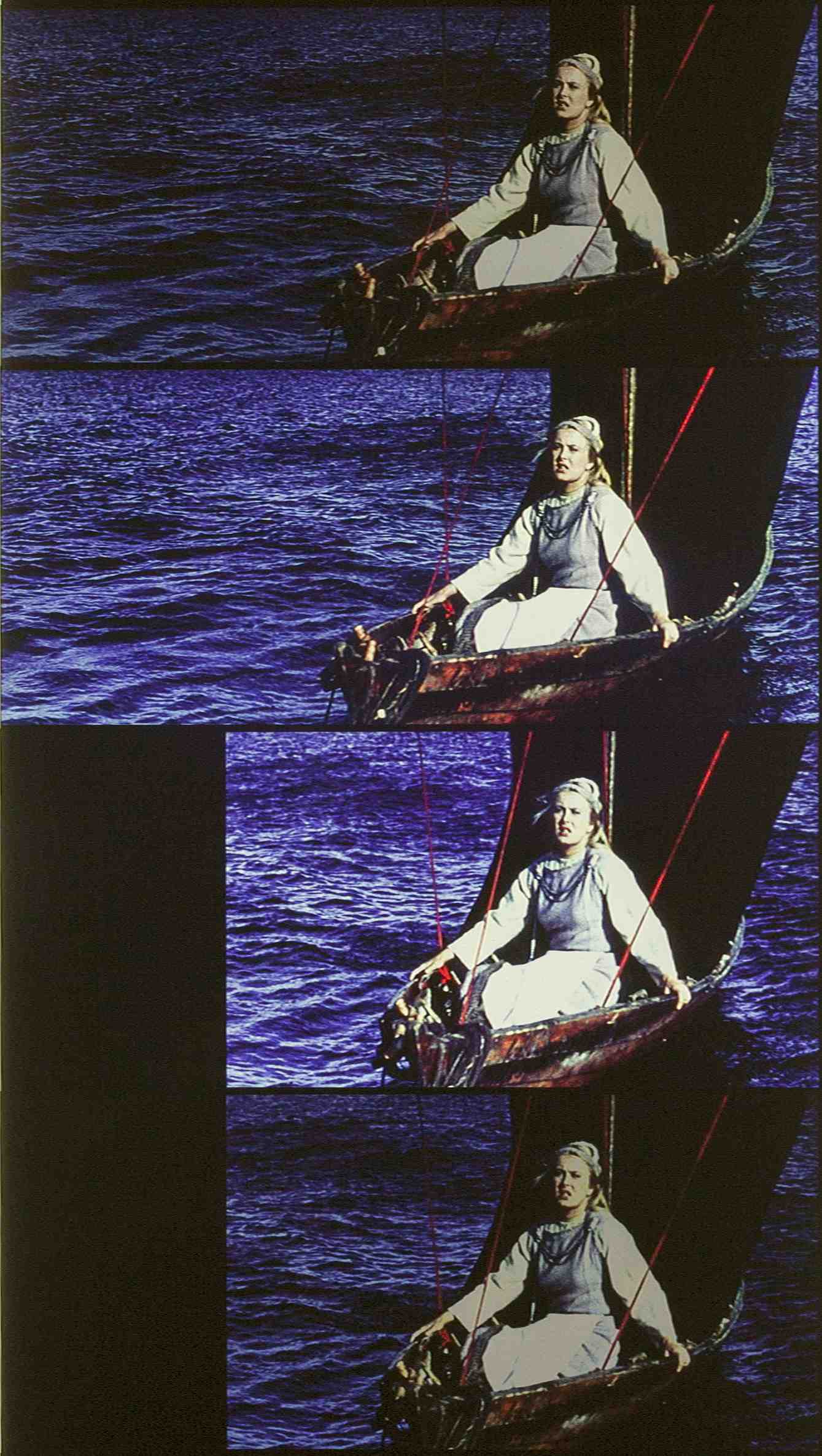

Hate (Sami van Ingen, 2012, 12 minutes, 35mm)

In 1959, Soviet film director Aleksandr Ptushko (1900–1973) directed a feature film called Sampo, which was loosely based on the Finnish national epic Kalevala. Parts of Sampo were filmed with two cameras simultaneously. In Hate, I generate a stereographic image from these two separate, but simultaneously captured images to form a “happening” between the different perspectives. In this work, I am interested in the possibility of exposing the hidden landscape of the mythical Kalevala for scrutiny and through this to open up questions over the way the other is portrayed and implicated in Ptushko´s depiction of Kalevala. The strobe-like visual quality of the work contrasts to the pictorial content that follows traditional narrative lines: the abduction of the fair maiden, the events lead to a disgraced and defensive suitor, who, once defeated, exits the set sulking.

Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine (Peter Tscherkassky, 2005, 17 minutes, 35 mm)

The identity of the protagonist of Light and Sound Machine oscillates between the depicted western cowboys and the cinematic apparatus itself, which aggressively inserts itself into the (viewed) structure of the film. Tscherkassky´s film constantly appears to be on the verge of destruction at the same time as it attempts to give visual birth to the cowboys’ appearance out of a dark void. Instructions appear and disappear. Tscherkassky attempts, in his own words, to transform a Roman Western into a Greek tragedy. Tscherkassky makes the circular graveyard spin seemingly uncontrollably and interminably, we are also repeatedly presented with the technical markings of the original print that were meant to be hidden from the audience.

BIO:

A great-grandson of Robert Flaherty, van Ingen spent his childhood in both India and Finland. After studying anthropology in London, he returned to Helsinki to co-found, in 1990, the Helsinki Filmmakers Co-op. Co-run by van Ingen for the next ten years, the Filmmakers Co-op converted the former Nokia Cable Factory into a working space for non-professional film production. Since 1989, van Ingen has been a member of the artists’ union Muu, in 1993 holding the position of chairperson. He has taught film at the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki since 1990, and in 1993 participated in the formation of the Industrial Situations Group. Van Ingen’s work with moving image and sound – for the most part within installation, film, and video – has been influenced by both documentary and experimental traditions. In 1995, he collaborated with Toronto filmmaker Philip Hoffman on Sweep (1995), and is perhaps best known for his informal ‘trilogy’ of films The Blow (1997), Days (2000), and Fokus (2004). van Ingen’s first major international retrospective was organized by Pleasure Dome, in Toronto in 2005. Finnish Academy of Fine Arts publishes Sami van Ingen’s Moving Shadows –Experimental Film Practices in a Landscape of Change (2012, 155 pages, Helsinki).