Part of Summer 2012

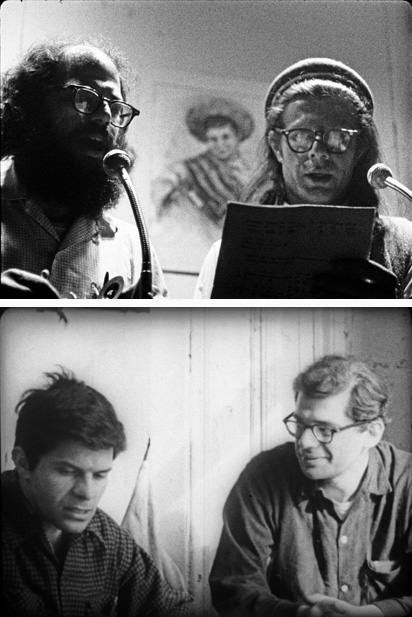

Me and My Brother (1969, 91 min.) is the first feature film by Robert Frank, who is perhaps best known for his photographs depicting the disparate layers of American society, as well as his candid documentary about the Rolling Stones, Cocksucker Blues. It begins as a portrait of the relationship between poet Peter Orlovsky and his brother Julius, a catatonic schizophrenic. Along with mentor and lover, Allen Ginsberg, Orlovsky shows his brother around the beat scene, until Julius wanders off and disappears without a trace. Unable to complete the film without Julius, Frank recasts actor Joseph Chaiken in the role, until Julius reappears years later. This bizarre film within a film (featuring a young Christopher Walken in the role of the director, overdubbed with Frank’s voice) blends fiction and reality to create a disorienting trip in which the idea of documentary “truth” is constantly being called into question.

[gallery]

He’s Not There: Robert Frank’s Me and My Brother

by George Kouvaros

Published online > www.screeningthepast.com

Number 29

“The world of which I am a part includes Julius Orlovsky. Julius is a catatonic, a silent man; he is released from a state institution in the care of his brother Peter. Sounds and images pass him and no reaction comes from him. In the course of the film he becomes like all the other people in front of my camera—an actor. At times most of us are silently acting because it would be too painful not to act and too cruel to talk of the truth which exists…. To complete this circle Joseph Chaiken, the Actor, plays Julius and becomes me at the same time.” (Robert Frank)

Robert Frank began work on Me and My Brother (USA 1968) with the intention of producing an adaptation of Allen Ginsberg’s long prose poem, Kaddish. The project foundered when it failed to attract the necessary financial support. But the time spent working on Kaddish sowed the seeds for another project with striking similarities to Ginsberg’s devastating account of his mother’s mental illness. For fifteen years, Julius Orlovsky, the brother of Ginsberg’s partner, Peter Orlovsky, had been a psychiatric patient at Central Islip State Hospital. On January 17 1965, Julius was released from hospital in the care of his brother. When Frank began filming their relationship, the two brothers were sharing a flat with Ginsberg on New York’s Lower East Side. Near the start of the film, Peter talks candidly about his frustrations with Julius’ catatonic behavior: “He gets up, but he doesn’t …doesn’t go to wash his face or brush his teeth or go to the bathroom …or start to make breakfast …He just gets up and stares at his mattress, his wrinkled sheets.” In a slightly earlier scene, Peter describes the effects of his brother’s medication to an audience at a poetry reading: “It’s worser than pot. It’s worser than marijuana—because it disinfocals yours eyes and disinfocals your bowels.” When Ginsberg and Peter press a microphone to Julius’ face, he responds to their urgings to speak by softly echoing their words: “Say something.”

During a trip to San Francisco, Julius disappears. This was not the first time that Julius had wandered off. In order to deal with the difficulties posed by Julius’ behavior and secure additional funding for the project, Frank hired the actor and theatre director, Joseph Chaiken, to play the role of Julius. Chaiken’s performance is complimented by a number of other professional actors: Christopher Walken and Roscoe Lee Browne play the role of a filmmaker shooting Julius’ story; John Coe plays Julius’ psychiatrist; and Cynthia McAdams plays an actress offering her views on the filming. When Me and My Brother was released, Jonas Mekas described its blending of fictional and documentary elements as “unbelievably phony.” “I seemed to like all of the footage,” he writes. “But I seemed to hate what was done with the footage. I kept cursing the editor.”[1] One week later, Mekas continued his ruminations: “I disliked Frank’s movie because he kept trying (he or the editor) to make it more meaningful, more important, more significant, deeper than the reality itself which was caught by Frank in the footage.” (p. 48) Nearly twenty years after its release, Frank, himself, offered an equally critical assessment of the film. He outlines the changes and difficulties that he had to deal with during the filming. Looking back on how he dealt with these changes, Frank feels he made a mistake: “I should have just accepted what was there and not try to make it into something else…. I really tried to twist it into a shape that I felt the film needed in order to be a full-length film. And now, if I was to re-edit the film or redo it, I would let it be the way the footage came out and not try to over-edit it or force it into telling a specific story.”[2] The disconcerting shifts between fictional and documentary approaches, the formal disjunctions between image and sound and the switching between colour and black and white film do make Me and My Brother a challenging cinematic experience. But far from discounting the film’s significance, they provide important clues for understanding both Frank’s emergence as a filmmaker and his place within a broader renegotiation of documentary and fiction filmmaking occurring during the ’60s.

Frank began work on Me and My Brother directly after completing two fiction projects: The Sin of Jesus (USA 1961), an adaptation of a short story by Isaac Babel, and OK End Here (USA 1963), which deals with a relationship that appears to be at the point of collapse. Both films exemplify a style of narrative storytelling in which the traditional emphasis on plot is replaced by a focus on inner states. But while both films constitute milestones in Frank’s development as a filmmaker, they also represent a retreat from the provocative mixture of documentary and fictional elements found in Pull My Daisy (USA 1959). Part of the significance of Me and My Brother, I want to suggest, is that it marks a meeting point, not only between documentary and fiction, but also between the style of serial composition found in Frank’s landmark photographic work, The Americans (1959), and his aspirations as a filmmaker. “[T]he impact of The Americans then as now,” writes W. T. Lhamon Jr., “hangs on its approach/avoidance conflict with narrative. [Frank] was always telling and denying a story, always catching and freeing a connection, encouraging and discouraging an interpretation.”[3] In the following, I want to consider how this ambivalent approach to narrative reemerges in Me and My Brother. This will shed light on one of Frank’s most important filmic works and contribute to a broader history of the intermedial aspects of postwar American filmmaking.

Falsifying Narration

“In this film all events and people are real. Whatever is unreal is purely my imagination.” Superimposed on a shot of an open bible, this statement serves to preface Me and My Brother’s intermingling of documentary and fictional elements. During the second half of the ’60s, these sorts of statements were part of a process of formal experimentation occurring across a range of contexts. In films such as Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot Le Fou (France/Italy 1965) and Deux ou Trois Choses que Je Sais d’Elle (France 1966), the acknowledgement of the filmmaking process distances the audience from the story and encourages reflection on its construction and effects. A reflexive engagement with the conventions of fiction is also evident in Me and My Brother. During the prologue, actors playing the roles of Peter and Julius partake in the filming of a sex experiment. Peter tries to justify the filming to Julius: “This is the movies, Julius. A little movie never hurt any body, especially a love scene. How can you be afraid of a love scene, Julius?” The psychiatrist overseeing the filming echoes Peter’s justifications: “All you have to do is behave however you behave in real life. You don’t have to act.” These justifications remind us of the camera’s tendency to objectify its subjects. More worryingly, they also acknowledge that there might be something exploitative in Frank’s own engagement with his central subject. The overall effect of the prologue is to forefront a set of questions that are echoed by the new cinemas of the ’60s: How do we film this story? What forms of narration could do justice to its central subject? In Me and My Brother, the constant shifts in perspective and style evidence Frank’s willingness to take up the formal implications of posing such questions.

In understanding Me and My Brother’s approach to narrative, Frank’s own account of the production difficulties provides a handy point of departure: “I started out to do a film about a poem of Ginsberg’s, and it ended up to be a film about Peter Orlovsky’s brother, whose name was Julius. So it continuously changed. Then you sort of focus on this person. And by what happens to him over a longer period of time, the film changes.” (p. 36) Taken at face value, Frank’s summation suggests an approach in which the style and content of the film is determined by the unfolding of events. But we can also read his comments as evidence of a creative tension, on the one hand, between Frank’s attempts to be responsive to the contingent events and changes that arose during the filming, and, on the other, the need to impose on these events and changes an element of formal coherence. Me and My Brother represents the articulation of a struggle that recurs throughout Frank’s films between the exhilaration of forging a work around the contingent events and occurrences that arise during a shoot and the need to find a form of narration capable of conveying the nature of these events and occurrences. Julius’ disappearances triggered a crisis in the production that Frank sought to deal with by hiring an actor. But its most important consequence was to force Frank to work through his own complex relationship to filmic narration.

Looking at an early sequence will shed light on this relationship. The sequence begins with a medium close-up of Julius in the apartment that he shares with his brother, Peter, and Allen Ginsberg. Moments earlier, we watched a clean-shaven Julius enter the apartment building. Now, however, he sports a neatly trimmed full beard. In his right hand, he holds a cigarette. A pan to the right reveals Peter getting a bottle of juice from the fridge. On the table next to Peter is a book: How to Live With Schizophrenia. From between the book’s pages, Peter retrieves a letter from the hospital where Julius was a patient. It describes Julius’ age and interests and the circumstances surrounding his first psychotic episode while working for the New York Sanitation Department: “He was masturbating while on duty. He became excited …violently resistive, and was transferred to the Kings County Hospital on October 31st, 1950. On November 10th, 1950 he was admitted to Central Islip State Hospital. He received electric shock treatment. Diagnosis was schizophrenic—catatonic type.” As Peter reads the letter, the camera pans back to where Julius is standing. Still holding the cigarette, he raises his right hand above his head and looks up. This action cues a cut to a new location. In this shot, Julius is clean-shaven and dressed in the uniform of a Sanitation Department worker. He is gazing at a large metal claw as it descends to collect a pile of garbage. During the next five minutes, we watch Julius, sometimes alone, sometimes with a small boy, move through a range of locations: the sanitation plant, an aquarium, a beach, a city street. Although neither Julius nor the boy speak, their actions have a sense of quiet purpose. While the boy examines the swirling particles of a snow dome, Julius carefully scrutinizes both sides of a one-dollar bill. The hand-held camera also records a series of events occurring around the central pair: a man in an overcoat and hat touches a bench just before sitting down; a group of elderly men and women walk past and glance at the camera. For a moment, it seems that these activities will cause the film to lose sight of Julius. But the camera’s peregrinations always return to Julius’ unassuming presence. The penultimate shot is of Julius, once again in his Sanitation Department uniform, pushing a newspaper along the street with a large broom. When Julius stops to gaze up at the surrounding buildings, the film cuts back to the earlier shot of him in the apartment with his hand in the air. The sequence ends with Peter concluding his reading of the letter.

By matching the shot of Julius in the apartment at the start of the sequence with a shot from exactly the same position near the end, Frank encourages the viewer to search the intervening images and sounds for some insight into Julius’ condition. But the oblique nature of Julius’ actions makes it impossible to determine how they might confirm or contest the diagnosis contained in the letter. The unexplained changes in Julius’ appearance are merely the most obvious indications of the instability that defines the film’s narrative. In a slightly later scene between Julius and the psychiatrist, Julius alternates between appearing clean-shaven and sporting a beard, just as the psychiatrist is shown both with and without a hairpiece. This simultaneous establishment and erasure of narrative information recalls Alain Robbe-Grillet’s discussion of the role of story and anecdote in the New Novel. “Even in [Samuel] Beckett,” Robbe-Grillet observes, “there is no lack of events, but these are constantly in the process of contesting themselves, jeopardizing themselves, destroying themselves, so that the same sentence may contain an observation and its immediate negation. In short, it is not the anecdote that is lacking, it is only its character of certainty, its tranquility, its innocence.”[4] Similarly, in Me and My Brother storytelling is not abandoned. Rather, it has taken on the task of rendering a world lacking in stable points of reference.

“[W]hether explicitly or not,” Gilles Deleuze reminds us, “narration always refers to a system of judgment: even when acquittal takes place due to the benefit of the doubt, or when the guilty is so only because of fate.”[5] The rise of “falsifying narration” shatters the system of judgment. It leads to the creation of pure optical and sound situations that lack the causal linkages of traditional narration. In describing the outcomes of falsifying narration, Deleuze also refers to the rise of characters whose identities are marked by an irreducible multiplicity: “‘I is an other’ [‘Je est un autre’] has replaced Ego = Ego.” (p. 133) We are close to the passages between fiction and documentary that define Frank’s engagement with Julius in Me and My Brother. Faced with a character whose situation shatters the system of judgment, Frank develops a storytelling method that takes on, rather than contains, the fractured identities of his central subject. Indeed, such is the complexity of the film’s formal structure that, from one moment to the next, it’s impossible to predict the stance taken by Frank’s film: documentary, fictional reconstruction or some blending of the two. At times, the shift in approach happens between sequences, for example, when Frank shifts from fictional enactment in the prologue to the employment of documentary filming during the poetry reading. At other times, it happens within individual shots, for example, when, in the middle of one of their sessions, the actor playing the role of Julius’ psychiatrist turns away from Julius and directs his remarks to the camera.

In an article that originally appeared in 1967, Noël Burch notes the way that in Andy Warhol’s The Chelsea Girls (USA 1966) the camera functions variously as a voyeur, a participant, and a distancing device. These shifts, Burch claims, suggest the ambivalence of the roles assumed by Warhol’s characters: “The film is a perpetual interplay of masks, in which the viewer finds it absolutely impossible to determine the part played by improvisation (whether free or within predetermined limits), the part played by the acting out of previously agreed-on gestures, and even the number of lines of dialogue actually decided on beforehand.”[6] In the case of Godard’s work, these shifts in the camera’s role are addressed in a more systematic manner. In Une Femme mariée (France 1964) alternations in the camera’s relation to the events it records are clearly indicated through the different forms of stylized presentation that the film assumes. In Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle these alternations in the camera’s relation to the action provide the film with “one of its essential underpinnings.” “The relationship between actor and camera may change at any moment,” Burch proposes, “even in the middle of a shot…. At times, the transition is obvious; at times, it becomes evident only after the fact; at times, the exact moment it actually occurs cannot be determined, although the viewer is vaguely aware that ‘there has been one somewhere.’” (p. 120)

Burch’s survey forefronts something that is also evident in Me and My Brother: an alternating passage of affect from camera to actor and actor to camera. These points of reference form a network of circulating affect in which different influences and relations get passed across and separations are constantly disturbed. The film emerges as a consequence of the shifts in relation among its participants. In the end, it is impossible to say if Me and My Brother is about Julius, or the various approaches adopted by Frank and his collaborators in a valiant attempt to tell Julius’ story. By destabilizing the distinctions between actor and camera, fiction and documentary, Frank becomes implicated in the story being told.

Radical Discontinuity

In Me and My Brother Frank conveys a strong sense of Julius’ disconnected relationship to everyday reality. At the same time, he affirms the capacity of cinema to manifest new forms of audio-visual storytelling. Me and My Brother is a film about Julius and his perception of the world. But it is also about cinema’s ability to transform itself through an engagement with its central subject. At the level of both narrative and audio-visual composition, the chief mechanism for affecting this transformation is discontinuity. In his survey of European modernist filmmaking, András Bálint Kovács draws attention to the role played by discontinuity in establishing new models of narration. As Kovacs explains, discontinuity describes the moment when a film’s reliance on joining independent fragments of images and sounds to establish the sense of a homogeneous surface reality is exposed. This is usually done through the institution of gaps or unexplained shifts in the film’s narrative. But discontinuity can also extend to the audio-visual fabric of a film. “I call these forms ‘radical’,” Kovács writes, “to emphasize their tendency to go beyond the usual measure of breaking or manifesting continuity in narrative art cinema. In both cases the reason for this stylistic ‘excess’ is to reflect the disconnected alienated, or one-dimensional character of empirical surface reality.”[7]

Kovács’ exemplar of radical discontinuity is Godard’s À bout de souffle (France 1960). Positioned to one side of Godard’s playful reworking of cinematic form, Me and My Brother stands as another manifestation of postwar cinema’s investment in discontinuity at the level of both narrative and audio-visual composition. It marks the point where the development of a radically discontinuous narration crosses paths with a style of serial composition usually associated with avant-garde film. Kovács describes serialism as a “radical form of narration where the logic of juxtaposition is more important than the interior composition of the images, and it can have a variety of different stylistic elements mixed together.” (p. 136) But because the juxtaposition of images and styles is at odds with the continuity requirements that underpin narrative forms, Kovács is unwilling to describe serialism as simply a more dispersed version of narrative: “Serial arrangement involves isolating certain types of formal elements from other types and in eliminating the hierarchical relationship between them. Thus, different stylistic layers will obey only their independent inherent logic.” (p. 136)

Kovács’ summation allows us to identify a driving principle of Frank’s work in film as well as photography: an isolation of formal elements to create intonations of meaning that resist narrative accommodation. In Pull My Daisy, Jack Kerouac’s voice-over speaks for each of the characters, their situations and place within the social gathering. But its overt performativity also creates a range of associations that exceed the film’s narrative agenda. Similarly, in Me and My Brother Frank’s use of non-synchronous sound creates a series of overlaps between disparate activities and events. This is evident during a conversation between a woman who goes by the name of Kismet Nagy, a self-described ageing alcoholic actress, and a character referred to in the script as simply the filmmaker (Roscoe Lee Browne). When these two characters encounter each other in the waiting room of the dental surgery where Julius is having his teeth checked, the woman claims to recognize the filmmaker from a previous meeting. She then proceeds to speculate about the filmmaker’s financial status and the nature of his occupation. She also provides the film with its most reflective moment: “Don’t make a movie about making a movie. Make it. Forget about the film—throw away your camera—just take the strip—wouldn’t it be fantastic if you didn’t even have to have a piece of celluloid between you and what you saw?” As if to visualize the consequences of this statement, during the course of Nagy’s monologue, we are presented with a montage of different locations and activities: Ginsberg and the Orlovsky brothers going about their early morning routines under the observation of the filmmaker; Nagy walking around in a vacant lot; the filmmaker flicking through a portfolio of photographs in which fashion shots are interspersed with images from The Americans; documentary footage of Manhattan traffic. Near the end of Nagy’s monologue, we see the filmmaker riding the subway. When the camera cuts to a close-up of the filmmaker, the first few lines of Nagy’s monologue are replayed over the sound of the subway carriage. As we move across these disparate activities, a thematic or sub-textual connection may become apparent. But if it does, it does so belatedly or in a way that disperses the film’s dramatic focus. This dispersal of dramatic focus raises a question that lies at the heart of the film’s formal construction: Whose story is this? In Me and My Brother the use of sound to link disparate activities and events is just one way that Frank creates a story that, like the central character, is always on the verge of disappearing or being replaced by other stories.

Essay Film

The idea of somebody or something on the verge of disappearing sums up the outcome of Frank’s reconfiguration of narrative in Me and My Brother and provides a link to one of postwar cinema’s most innovative genres: the essay film. It was Hans Richter who coined the idea of the essay film to describe a form of cinema sitting between documentary and fiction. The primary goal of this third form of cinema, Richter argues, is to make “problems, thoughts, even ideas” perceptible and to “render visible what is not visible.”[8] More recently, Adrian Martin has also drawn attention to the speculative nature of the filmic essay. “In English as in French,” observes Martin, “the word essay implies not only a form, but an activity: to essay, to try out, to test the limits of something.” It is characteristic of the true essay to keep the identity of this something open: “[The essay] gives the impression of discovering what it is about as it goes along—as it observes the world, collects data, makes connections and draws associations …Thus, the true essay must start out without a clear subject, let alone a clear thesis that will be illustrated or confirmed.”[9] In Me and My Brother, Frank began with a clear subject. But as we have seen, this subject kept changing and eluding the director’s intentions. The film’s impact is based on the way this loss of control is also central to our experience of the film. The shifts between Julius-the-actor and Julius-the-real-person and the breaks in narrative and audio-visual continuity manifest this loss of control. But they also suggest a series of connections, intuitive rather than logical, that shed light on the nature of Julius’ world. The outcome is a series of ideas about Julius grounded in Frank’s own relationship to his central subject.

We need to be clear about how these intuitive connections are established. On one level, this involves the use of formal devices such as overlapping sound. On another, the connection involves a correspondence between the film’s fictional and documentary agendas. Thus, towards the end of the film, Joseph Chaiken looks directly at the camera and states: “My speech is all used up. I have nothing else to say. I’ve nothing else to read from—I don’t know who to play.” Is Chaiken still in character? Or, is he signaling the conclusion of his performance? Elsewhere, the connection between events involves an activity that indicates a larger pattern of behavior. We first become aware that Julius has been located during a scene in which Peter and Gregory Corso listen to Ginsberg reading a letter from Napa State Hospital. The letter describes the behavior of a newly admitted patient, “George Orlovsky,” who refuses to answer questions put to him by hospital staff. Ginsberg’s reading of the letter recalls the much earlier scene when Peter reads the letter from Central Islip State Hospital. When Ginsberg concludes his reading of the letter, the film cuts to Julius’ discharge from the hospital in black and white. On the soundtrack, Frank questions Peter about the events of that day and his reaction to Julius’ newfound lucidity. He wants to know why Peter began to sweep the floors of the hospital: “You must be out of your mind.” As we watch Peter’s manic behavior, again, we register the echo of an earlier scene: Julius in his Sanitation Department uniform sweeping a newspaper along the street. The purpose of these repetitions is not to confirm a diagnosis that might explain Julius’ predicament. Rather, it is to establish something more elusive: the dispersal of meaning across different contexts, situations and figures. Through this process of dispersal, Frank parlays Julius’ story into a much larger story about acting, his own struggles as a filmmaker and the people and events that surround his central character.

The closest we get to a direct account of Julius’ predicament occurs during the final moments. Frank asks Julius about the shock treatment, his views on Ginsberg and Peter, and how he feels about acting. “Acting is something beyond my collaboration,” Julius responds. “Acting is beyond my, my ah thought processes sometimes …It may be a waste of time.” When Frank directs Julius to say something to the camera, he replies: “Well, the camera is a …seems like a—a—a—a—a—a—a—reflection of disapproval or disgust or—disappointment or unhelpfulness—ness, or …unexplainability—to disclose any real, real truth that might possibly exist.” Frank then asks Julius where does truth exist: “Inside and outside—the world. Outside the world is—well—I don’t know. Maybe it’s just a theory, an idea or a theory is all we can arrive at—a theory or an explanation—to the matter—whatever you concern yourself with.” Given everything that has happened until now, Julius’ acute observations represent a triumph—for Frank as well as Julius. But the extraordinary thing about these final moments is the way Julius’ observations are captured. Frank films Julius from the other side of a glass window. Every now and then, we catch sight of the cameraman’s reflection on the glass surface. The switch from black and white back to colour reinforces this overt rendering of the filming. And as if on cue, when Julius delivers his verdict on the camera’s limitations, drops of rain start to cover the surface of the window. Once again, Julius seems to be on the verge of disappearing. Out of the contingent circumstances of filming, Frank fashions a visual metaphor perfectly suited to his central character’s precarious engagement with the world.

Frank’s filmic approach thus has at its core not just discontinuity, but also an acute level of responsiveness to the discoveries that arise during shooting. Describing the particular form of attention manifested in Frank’s photographs, W. S. Di Piero identifies “a preparedness for the revelatory pattern in a given scene so natural and primed that it is indistinguishable from mere reflex.”[10] One of the things that Frank found both challenging and appealing about film was that it required a much greater degree of deliberation and interaction with others. “As a still photographer I wouldn’t have to talk to anyone,” Frank remarked. “You’re just an observer; you just walk around, and there’s no need to communicate …. Whereas with films it becomes more complicated—thinking in long durations and keeping up a kind of sequence.”[11] Me and My Brother marks a turning point in Frank’s career. It affirms his capacity to invest the deliberations and procedures of filmmaking with the present tense revelations and responsiveness that characterize his work as a photographer. This involves placing himself in the picture, not as a controlling force, but as someone open to the missteps and fortuitous occurrences that can arise during a shoot. It also involves a model of narrative that takes its cue from the correspondences and formal overlaps that structure the story told in The Americans.

Viewed from the perspective of Frank’s career, film and photography have as their motivating principle the search for forms of narration capable of evoking the unresolved nature of experience. The final echo of this principle occurs when Frank asks Julius to look directly into the camera and say: ‘My name is Peter.’” When Julius obliges, Frank corrects him: “No, your name.” In Me and My Brother Julius’ inability to reconcile inside and outside crosses paths with Frank’s struggle to bring together a film that keeps changing shape. The thing that should never be forgotten is that, whereas Julius is dealing with psychological processes beyond his control, Frank has the luxury of being able to step back and draw out of the various difficulties encountered during the shooting a form of cinematic narration capable of reconciling creation with destruction, making and unmaking. It is this capacity to evoke, and place in check, an identifiable story that defines both Frank’s account of Julius’ world in Me and My Brother and a new kind of postwar narration passing between media.

Endnotes

[1] Jonas Mekas, “Movie Journal,” in Robert Frank: New York to Nova Scotia, ed. Anne Wilkes Tucker (Göttingen: Steidl, 2005), 45. Further references to this text appear as page numbers in brackets.

[2] Robert Frank, “Highway 61 Revisited,” Robert Frank Interviewed by Marlaine Glicksman, Film Comment 23, no. 4 (July-August 1987): 36. Further references to this text appear as page numbers in brackets.

[3] W. T. Lhamon Jr., Deliberate Speed: The Origins Of A Cultural Style in the American 1950s (Washington and London: Smithsonian institution Press, 1990), 128.

[4] Alain Robbe-Grillet, For a New Novel: Essays on Fiction, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Grove Press, 1965) 33.

[5] Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), 133. Further references to this text appear as page numbers in brackets.

[6] Noël Burch, “Chance and Its Functions,” in Theory of Film Practice, trans. Helen R. Lane; introduction by Annette Michelson (New York and Washington: Praeger Publishers, 1973) 117. Further references to this text appear as page numbers in brackets.

[7] András Bálint Kovács, Screening Modernism: European Art Cinema, 1950—1980 (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 126. Further references to this text appear as page numbers in brackets.

[8] Hans Richter, “The Film Essay: a New Form,” quoted in Nora M. Alter, Chris Marker (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2006), 17.

[9] Adrian Martin, “Robert Kramer Films the Event,” Rouge 9 (June 2006) http://www.rouge.com.au/9/kramer_films_event.html June 2006

[10] W. S. Di Piero, Out of Eden: Essays On Modern Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 180.

[11] Robert Frank, “Robert Frank” in Photography within the Humanities, ed. Eugenia Parry Janis and Wendy MacNeil (Danbury, N. H.: Addison House Publishers, 1977), 53.

Published online > www.screeningthepast.com

Founding Editor: Ina Bertrand

Editors: Anna Dzenis and Raffaele Caputo

Online Editor: Cerise Howard