Part of Winter 2010

This trio of experimental films produced by the McMaster Film Board are a time capsule of the late-60s radical student counterculture. Though thought to be lost, To Paint the Park (1968) was rediscovered and Palace of Pleasure (1966/67) restored by Ryerson PhD candidate Stephen Broomer. Along with Buffalo Airport Visions (1967), the films in this programme present a synaesthetic mash-up of the sights and sounds of the era, and Stephen Broomer will be on hand to discuss the films.

Programme:

Palace of Pleasure, John Hofsess (1966/67, 38 min.)

Buffalo Airport Visions, Peter Rowe (1967, 19 min.)

To Paint the Park, David Martin (1968, 23:25 min.)

Stephen Broomer is a Toronto-based graduate researcher and visual anthropologist. My documentary films focus on civic architectural, environmental, and social concerns – from hydro-electric architecture, to public art installations, to ecological preservation initiatives, to homeless counts. As a writer, he is developing work on the social history of Canadian cinema.

Notes:

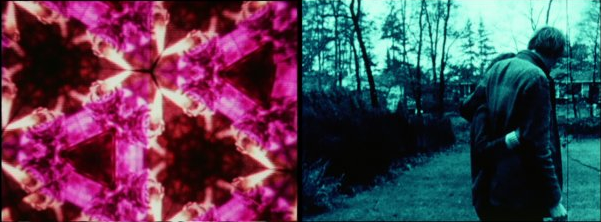

“Buffalo Airport Visions is a document of Toronto bohemian life in 1967. It contrasts footage of streetlife with scenes from the University of Toronto psychedelics festival, including Greenwich Village beat-rockers The Fugs, and from the set of an early David Cronenberg film. When the Velvet Underground performed at McMaster University in 1966, it was filmmaker Peter Rowe’s task to drive them. His experience picking up Nico at the Buffalo airport inspired this film’s title.

Rowe was the first president of the McMaster Film Board, and along with John Hofsess and Patricia Murphy, its co-founder. His early work, such as The Neon Palace, fits him into an experimental documentary tradition, with a significant emphasis on documenting his generation. Buffalo Airport Visions was his first solo film, but he was initially credited as co-director of Black Zero, the second segment of Palace of Pleasure.

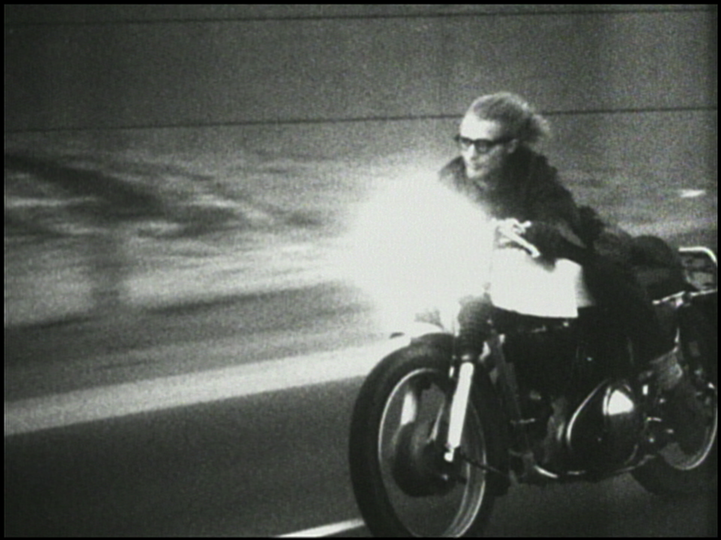

To Paint the Park depicts a young student pair (a male artist and a female model) frolicking in a park. His desire for her is thwarted by her evasion, alternately playful (a carefree chase) and ominous (adopting a hideous transparent mask). As he pursues her, the vivid life of the park – its green fields and blue waters – give way to psychedelic interruptions, the torment of his desires manifested in images of a gang of motorcyclists. When he finally captures his muse, she vanishes.” S. B.

Lost and Found, Jason Anderson, Artforum 01.22.09

THE VALUE OF John Hofsess’s Palace of Pleasure (1966/67/68) as a trippy time capsule of Canada’s nascent ’60s film underground would be apparent even if it didn’t include the sight of a young, shirtless David Cronenberg slipping into bed with a nude man and woman. The future director of Videodrome (1983) and Crash (1996) was one of several Ontario students cast as actors in Hofsess’s ambitious scheme to fashion an appropriately mind-bending and taboo-busting cinematic response to the era’s tumults, one that was directly inspired by a 1966 appearance at McMaster University (where Hofsess went to school) by the Velvet Underground and the Exploding Plastic Inevitable.

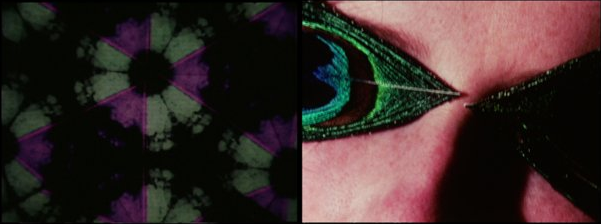

Along with poems by the not-yet-famous Leonard Cohen, the fuzz-laden death rattle of the VU’s “European Son” is a key part of the aural accompaniment to Hofsess’s thirty-eight-minute film, which will have its first public screening since 1968 at Cinematheque Ontario. (The program pairs it with Ronald Nameth’s 1967 document of another EPI extravaganza.) While there’s not much shock value left in its juxtaposition of grisly Vietnam War footage, kaleidoscopic abstract imagery, and shots of Hofsess’s classmates performing erotic, vaguely Crowleyite rituals, Palace of Pleasure nevertheless retains a raw vitality. With its vibrant color palette, use of multiple projectors, and rapid cuts, Hofsess’s film still induces the intended sensory overload.

Long thought lost, the work was recently restored by film scholar Stephen Broomer after a print was discovered in the archives of the Canadian Film Institute. When it first began to circulate in 1967, Palace of Pleasure was an early triumph for the country’s independent film community. At the time, it screened at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and represented Canadian film at a presentation at the National Film Theatre in London; there were also short theatrical runs in Los Angeles and Chicago. Jonas Mekas and Gene Youngblood even cited it as one of the best films of the year.

Back home, the film’s more risqué imagery earned it great notoriety, foreshadowing the furor that would greet Hofsess’s next filmmaking effort, The Columbus of Sex (1969), a sexploitation mockumentary that would incur obscenity charges for its makers. Hofsess later became a film critic for Maclean’s magazine and wrote the first book-length study of Canadian filmmakers. But his own achievement with Palace of Pleasure went underheralded, as the few prints disappeared into archives or were lost altogether. Its resuscitation serves as strange and startling evidence that even a sleepy campus in Hamilton, Ontario, wasn’t safe from the fiery energies of youth in revolt.