Part of Summer 2008

With a focus on the quotidian details of the environments she records both aurally and visually, Rosalind Nashashibi is an artist whose remarkable practice transforms the ossified conventions of documentary filmmaking and the protocols of ethnography. This first Canadian survey of her single-screen films presents a range of seven works (presented on 16mm and video) produced between 2000 and 2005, documents of the spaces and times of sites in Glasgow, Palestine and the United States.

In her films Nashashibi favours room tone over reportage, using her preferred medium of 16mm to investigate the surface of the image, her camera skimming the textures she has photographed in order to emphasize both tactile specificity and the localities of landscape, objecthood and citizenship. In addition, she develops a montage strategy where long, static takes are fragmented only to be revisited by the artist over the course of a film, marking both an imminent return to the image and the consequences of the passage of time.

While the often static framing in her works connects them to the structural film genre, they refuse any formalist reduction through the contested sites she has herself recorded, and therefore, occupied, politicizing the body of the filmmaker. She simultaneously underscores the real conditions of mobility and space faced by the people whose communities she enters, and their relation to those viewers who are free to stop, watch and leave.

Skip, Divided: The Films of Rosalind Nashashibi is presented in conjunction with the installation Rosalind Nashashibi: Bachelor Machines, the artist’s first gallery presentation in Canada at the OCAD Professional Gallery, 100 McCaul St., opening June 26th and running until August 31th. Please consult the OCAD website for additional details and information regarding the exhibition.

Rosalind Nashashibi is an interdisciplinary artist currently based in Glasgow. After completing her undergraduate degree at Sheffield Hallam University and her MFA at the Glasgow School of Art, she went on to become the first woman to win the Beck’s Futures prize in 2003. Her group exhibitions include Around the World in Eighty Days at the ICA in London, and the Scottish Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale, while her solo exhibitions include projects at the Chisenhale Gallery in London and the Berkeley Art Museum. Her films are distributed by LUX, and she is represented by doggerfisher (Edinburgh) and Harris Lieberman (New York).

Programme Notes:

Skip, Divided: Rosalind Nashashibi Single-Screen Films 2000-2005

This first Canadian survey of Rosalind Nashashibi’s single-screen films focuses on seven works produced between 2000 and 2005. With a focus upon the quotidian details of the environments she records, both aurally and visually, her films transform the ossified conventions of documentary film, and the protocols of ethnography. She favours room tone over reportage, using her preferred medium of 16mm film to emphasize the surfaces she has photographed, in order to investigate the tactile specificity of landscape, objecthood and citizenship. In addition, she develops a montage strategy, where her long, static takes are fragmented, only to be revisited by the artist over the course of a film. This marks an imminent return to the image, reshaping the passage of filmic time. While the static framing of these works establishes a connection to the forms of structural film, they refuse any formalist reduction through the contested sites she has herself recorded, and therefore occupied, politicizing the body of the filmmaker. Nashashibi’s practice contrasts the real conditions of mobility, and space, faced by those living in the communities she enters, to the viewer who is free to enter, observe and exit.

Structural film is a tendency of experimental filmmaking that P. Adams Sitney identified as emerging out of the avant-garde during the nineteen-sixties in an essay originally published in Film Culture in the summer of 1969. For Sitney, structural film insists on its shape, and what content it has is minimal and subsidiary to the outline. He proposed that the four characteristics of the structural film are: the flicker effect, loop printing, rephotography off a screen and a fixed camera position.1 While Nashashibi focuses upon the form of the fixed frame, within this body of films, she does not concentrate upon other aspects related to structural film, such as the apparatus or material of cinema. She records people and their environment, instead of strictly exploring a form. Rather than connecting her practice solely to the lineage of structural film, her use of the long, static take also points the viewer towards documentary, and the reception of the image as a record of the site the filmmaker has entered.

All of the films in Skip, Divided undermine traditional documentary structures; the people and places that she records are not prefaced or unpacked for the viewer, who is immediately immersed in the environment recorded. This is perhaps most evident in the lack of subtitles in any of the films presented. The viewer is given no aid to understand what is transpiring before the camera. Even when Nashashibi travels to a site where English is spoken, such as Nebraska where she produced the companion pieces Midwest (2002) and Midwest: Field (2002), there is no attempt to focus upon speech as a channel to produce meaning, or contextualize actions. In her essay “Nothing Happens: Time for the Everyday in Postwar Realist Cinema”, Ivone Margulies quotes Margeret Mead, regarding the relation of ethnography to the fixed camera’s potential for objectivity: “The camera or tape recorder that stays in one spot, that is not tuned, wound, refocused, or visibly loaded does become part of the background scene, and what it records did happen.”2 This may be true, but as we all know, each film retrieved from the camera becomes a record as much of the filmmaker, their perspective, and position, as their subject. Mead did not acknowledge that the objective position of the static camera always reveals the presence of the filmmaker, the encounter of a body with a site and it’s concrete consequences. In the case of Nashashibi, it is a very particular politicization of the artist’s body in relation to the mobility restrictions placed upon Palestinian citizens.

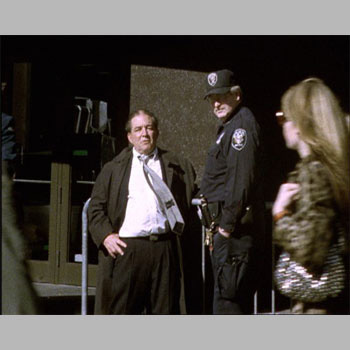

Nashashibi’s Palestinian heritage has been most noted in relation to two of the films that she has produced in the region, Dahiet al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002) and Hreash House (2004). In the former, she enters the East Jerusalem neighbourhood that her grandfather, Saeb Nashashibi, authorized, designed and built in 1956. She captures it as a crumbling no man’s land, stranded between the borders and jurisdictions of Israel and the West Bank. The latter film reveals an extended Palestinian family, living collectively in Nazareth during a feast and it’s aftermath during Ramadan. Entering as a British citizen, she is an outsider, and not subject to the restricted mobility placed on the movement of Palestinians, who are denied freedom of movement or access to areas of Israel and the occupied territories depending upon their citizenship status.3 The films presented as part of Skip, Divided demand that the viewer account for the politicized presence of the body of the filmmaker and ask themself what does it mean for a Palestinian woman to travel to Israel, and the occupied territories, in order to record the landscape and people there? What does it mean for a Palestinian woman to be recording the public spaces in the U.K., as in University Library (2004), or the actions of American police as in Eyeballing (2005)?

The films of Rosalind Nashashibi negotiate a relationship between filmmaker, and subject as well as document, and viewer, based upon the distance of an outsider looking in. They are the temporary meeting of two disparate forces, whether that is Nashashibi herself, as she enters and exits the places she has recorded, or us, as viewers who remain at an even further distance, watching the film, often at the periphery of the socio-political milieu documented. As Mark Godfrey notes in his Artforum essay on Nashashibi, it is in The States of Things (2003) that the tension between the disjunctive elements that permeates her films begins to be reconciled through the separation of sound and image, formulating a hybrid text.4 Here, images of a Glasgow jumble sale are set to a 1920’s love song by Egyptian diva Um Kulthoum, in the only film where Nashashibi purposely blurs or conceals her site.

Like the work of Redmond Entwistle and Jenny Perlin, two other artists primarily producing work in 16mm who are also exploring the concealed, intersecting histories of nationalism and politics, all of Nashashibi’s films presented here circulate as both archival and material fragments, offering only an entrance to the places and people she documents, leaving it to the viewer to uncover the depth and assemble the details that remain unseen for themselves.

-Jacob Korczynski

Programme

University Library (2004), 7 minutes, 16mm (transferred to video)

Midwest (2002), 12 minutes, 16mm

Dahiet Al Bareed, District of the Post Office (2002), 6 minutes, 16mm (transferred to video)

Midwest: Field (2002), 3.5 minutes, 16mm

Hreash House (2004), 20 minutes, 16mm (transferred to video)

The States of Things (2003), 3.5 minutes, 16mm (transferred to video)

Eyeballing (2005), 10 minutes, 16mm

Notes

1 P. Adams Sitney, “Structural Film” in Film Culture Reader, P. Adams Sitney, ed. (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970), 327.

2 Ivone Margulies, “Nothing Happens: Time for the Everyday in Postwar Realist Cinema” in The Everyday, Stephen Johnstone, ed. (London: Whitechapel; Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press, 2008), 127.

3 Office of the United Nations Special Co-ordinator, “The Impact of Closure and Other Mobility Restrictions on Palestinian Productive Activities: 1 January 2002- 30 June 2002,” United Nations, http://www.un.org/News/dh/mideast/econ-report-final.pdf

4 Mark Godfrey, “First Take: Rosalind Nashashibi,” Artforum, January 2007, 127.