Part of Winter 2004

Sponsored by the Images Festival

Pleasure Dome and the Images Festival are pleased to present Ian Toews’ guest curated programme Origins of Japanese Experimental Cinema. Kick off your film and video year with this extremely rare screening of works ranging from Shuji Teruyama’s seminal underground classic Emperor Tomato Ketchup (1970) to Takashi Ito’s eye-bending masterwork Spacey (1981) – probably your only chance to see some of these films in their intended format.

“The 1960’s started with the translated publication of Jonas Mekas’s classic “Towards a Spontaneous Cinema; A New Trend of Film in the United States.” This article had an impact on the young Japanese filmmakers who like John Cassavetes, Maya Deren, and Stan Brakhage sought something very different than the national cinema’s dominant industrial model. The 1960s were in Japan, as in almost everywhere in the industrialized world, a decade of massive significance for arts, society, and culture. In 1968 Japan’s first co-operative, The Japan Underground Centre, opened its doors. This period culminated in the 1971 European film festival sensation, Emperor Tomato Ketchup (immortalized by the French band Stereolab’s album of the same name). Another film that had a major impact at home and overseas was Navel and The A Bomb. A strongly stated metaphor for the death and rebirth of the post atomic bombed Japan. The film also demonstrates one of the more peculiar stylistic traits of Japanese experimental cinema that I feel is central to the Japanese avant-garde – sensationalism. In Navel and The A Bomb and Emperor Tomato Ketchup there are many scenes that are not easily forgotten.

In many ways sensationalism has yet to be forgotten, at least by the likes of Oshima, Kitano, and others others who can’t resist sex, blood, and violence. Still Japanese experimental cinema is vast and has much more to offer. This programme has its share of shock value, but also some of the most technical and aesthetically sophisticated films that I have ever seen.”

(Ian Toews)

Programme:

Navel and The A Bomb, Eiko Hosoe, 1960, 10:00 min.

A strongly stated metaphor for the death and rebirth of the post atomic bombed Japan.

My Movie Melodies, Junichi Okuyama, 1980, 6:00 min.

A structural film where the light properties of the image on celluloid simultaneously determine the sound. Evokes the works of Paul Sharits.

Burning Star, Kenji Onishi, 1996, 20:00 min. (short version)

Condensed from the original, the filmmaker comes to terms with his father’s death.

Flesh, Tachibana Karou, 1993, 6:00 min.

A portrait of a strong man.

Spacey, Takashi Ito, 1981, 10:00 min.

Ito came to international prominence with the film Spacey. Based on 700 photographs of a university gym, Spacey creates a series of dizzying visual movements that break into one multiple layered space after another.

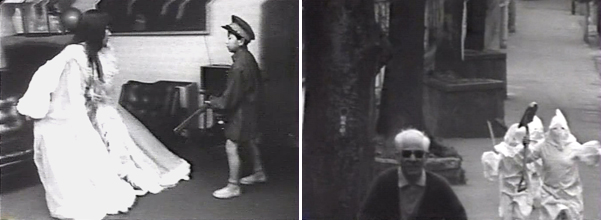

Emperor Tomato Ketchup, Shuji Teruyama, 1970, 27:00 min. (short version)

“A highly controversial film where children rebel against their oppressive parents. Called a perverse Lord of the Flies. An incredibly beautiful film.” (Ed Halter)

“I have lived in worked as a filmmaker in Japan for nearly two years. In that time I’ve studied Japanese culture, history, and its films as part of my own filmmaking. My aim with this programme is to provide some understanding of Japan, it people, its history, and its cinema through the study of these unique and rarely seen films.

There are no Japanese short films in existence that predate about 1955. This programme therefore represents more or less the historical canon of Japanese short movies. This period of time is of course of massive significance for Japan &lrquo;” it begins in the devestating wake of WWII and leads to the nation’s meteoric rise to global economic superpower.

Films like Navel and The A Bomb (1960) explore the death and rebirth of Japan by the Atomic bomb; while Emperor Tomato Ketchup (1970) address facism as an initially naive and immature impulse. As Japan grows and prospers the film works begin to concern themselves less with politics and history and more with the art of cinema. We then see technically masterful films, like the animated Spacey (1981), which was a sensation on the intenational film festival circuit in its day.” (Ian Toews) iantoews@yahoo.com

Notes on Emperor Tomato Ketchup

“For some, the more sensationalist aspects of Emperor Tomato Ketchup may eclipse the political acuteness of the film. With a moral rage akin in some ways to the anti-Thatcherite rant of The Cook, the Thief, his Wife & her Lover, the film skewers the conservative ethos of the generation that Emperor Hirohito ushered through the war and the hippie utopia of the generation that followed. Adulthood is considered so corrupt and irredeemable that the children rise up to take control. However, the violence and fascism with which the children assume control shows how easily the children subsume the sins of the parents.

Precursors to the shin jin rui, the “New Human” generation of Japan (borrowed and translated by Douglas Coupland as “Generation X” ), the youth of ETK are unable to imagine a utopia beyond the failed attempts of their parents. Instead they look towards the future with an intense nihilism, dressing up and appropriating adult roles, but facing the future with a certain blankness. It is shocking to see children of the early seventies adopting the punk codes that their peers would display only six or seven years later in London and New York’s club scene (the Xs the children wear are not that far from the reappropriated swastikas and visual iconoclasm of the Sex Pistols).

Not unlike Jean-Claude Lauzon’s Léolo, the coming of age of the children is treated in a rather shocking way. The initiation of a young boy by a trio of masked women is most fascinating in the sense of disinterest from the boy – the advances are either rebuffed or playfully turned into something completely non-sexual. After (literally) dragging Japan’s schoolteachers through the mud, the film ridicules the utopia of the free love generation, while not providing any solution. Five years earlier, this scene would have found the boy absorbed into the status quo of hippiedom – a rite of passage towards sexual enlightenment. Instead, Terayama’s acerbically funny vision finds the boy fighting back, turning from free love to a self-nullifying, but more realistic future.

Allowing children to play out the role of the oppressor is a disturbing vision for the future. The audience is challenged: not sure where to laugh and whether to concede to the filmmaker’s vision. However, much like Animal Farm, the power dynamics of a particular time are much more clearly seen when represented as a farce with substitute actors. Terayama’s farce is as stunningly moving as it is shocking, as iconic as the characters are iconoclastic. No serious look at the history of Japanese experimental film is complete without considering Shuji Terayama’s work. By the time he died in 1983, he was considered an institution in Japan because of his serious impact in and support of Japanese dance, theatre and avant-garde film (Misawa City, his hometown, boasts a Shuji Terayama Museum in his honour). While he was a very prolific filmmaker during the seventies with six films of his films screening at Cannes (his complete works span 7 VHS volumes), Emperor Tomato Ketchup is his best known film internationally. It kicked off the first Rotterdam Film Festival in 1971 and proceeded to careen around the festival circuit for a number of years, taking its place besides other cinema grotesques like El Topo, which equally traced the fall-out of flower power in the face of the betrayals of post-1968. Part of its notoriety stems from its rarity, so it’s a pleasure to screen such a beautiful print, straight from the archive of Image Forum in Japan.” (Chris Kennedy)