Part of Summer 2002

A co-presentation with Splice This! (June 21 – 23)

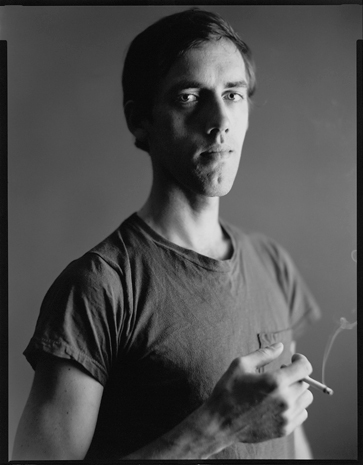

Infamous and famous at the same time, David Wojnarowicz, a New York-based artist, collaborated with such figures as Peter Hujar, Nan Goldin, Richard Kern, Tommy Turner and Phil Zwickler. Defying all categorization, and in some cases, absolving authorship altogether, Wojnarowicz has made an exhaustive body of work that remains, to this day, the reference for activist art in America. Painter, sculptor, photographer, writer, filmmaker; he was the sort of quintessential multidisciplinary artist that few can emulate. Diagnosed HIV+ in 1987, he became involved with politics, publicly denouncing the Church and the Reagan regime. Ironically, he was able to finish most of his collaborative films, but did not complete most of his own films.

This is the first programme of his work shown in Canada, spanning 30 years of image-making, from an early AIDS PSA announcement, to his outrageous performances for the notorious East Village filmmaker Richard Kern, to the recently restored 28 minute trailer Where Evil Dwells (for the intended, but never completed feature Satan Teens), a raw, hallucinatory biopic of the teenage “Satanists” killer Ricky Kasso and his gang, that draws on elements of Turner and Wojnarowicz’s own lives. Presented with the help of The Estate Project for Artists with AIDS and the David Wojnarowicz Foundation. A catalogue will be available at the screening.

Programme:

Fear of Disclosure: The Psycho-Social Implications of H.I.V. Revelation, Phil Zwickler and David Wojnarowicz

video, 1990, 5 minutes

Where Evil Dwells (The Trailer), Tommy Tunner and David Wojnarowicz

Super 8 to 16mm, 1985, 28 minutes (restored by the Estate Project under the supervision of Tommy Turner)

You Killed Me First, Richard Kern (Actor: D.W.)

Super 8 to DVD, 1985, 12 minutes

Manhattan Love Suicides (Stray Dogs), Richard Kern (Actor: D.W.)

Super 8 to DVD, 1985, 10 minutes

Fire in My Belly, David Wojnarowicz

Super 8 to 16mm, 1987, 8 minutes (silent) (unfinished, constructed by the Estate Project)

Heroin, David Wojnarowicz

Super 8 to 16mm, 1979, 3 minutes (silent) (unfinished, constructed by the Estate Project)

Film Art Life (Death, Sex, Social History): David Wojnarowicz by Ian White

“Each painting, film, sculpture or page of writing I make represents to me a particular moment in the history of my body on this planet, in America.” (“Do Not Doubt The Dangerousness of the 12-Inch Politician” )

“Expression without compromise, David Wojnarowicz’s work mounts as radical a challenge to the containment of commentary as it does to personal and cultural commodification: totemic, narrative and metaphorical paintings; iconoclastic photographs and montages; gory, transgressive multimedia installations; transient performances; fine art graffiti; diaries, political journalism, semi-fictionalized stories, imaginary monologues; collaborative films; finished/unfinished personal films; political video. Defying assimilation with the wild rigour of autobiography, it’s a body of work that lays the body of the artist on the line, lays US on the line.

The diary is pivotal for Wojnarowicz. His scrapbook-style journals ricochet into the rest of his writing as his super 8 diaries, shot between compulsion and intent, ricochet into a comparable visual lexicon, and the two are intrinsically linked. Images are translated from super 8 into the iconography of his paintings, frames become photographic stills, sequences are used and reused in performances and installations. Journal entries detail primitive storyboards, re-document and mirror films already shot, repeat themselves, are repeatedly translated into other written works, and spiral into images which resonate and repeat in turn.

Four of Wojnarowicz’s personal films have recently been reconstructed (as yet minus their soundtracks) by the Estate Project:

Heroin (originally 1979, b/w, 5:00 min.), Fire In My Belly (originally 1987, colour & b/w, 20:00 min.), Peter Hujar (originally 1987-88, b/w, 15:00 min.) and Howdy Doody Goes for a Ride (originally 1989, b/w, 25:00 min., the only one of the four significantly dependent on absent dialogue).

Wojnarowicz witnessed the AIDS-related illnesses, hysterical and desperate searches for cures, and eventual death of photographer Peter Hujar, one of his closest friends, in 1987 and within a year was himself diagnosed as HIV+. The most tender of extended, furious litanies, between text and image, across space and time, Hujar’s (life and) death is but one paradigmatic event that literally and ritualistically figures and reconfigures:

“I can’t form words these past few days. Sometimes I think I’ve been drained of emotional content, from weeping or from fear. Have I been holding off full acceptance of his dying by holding a mane camera – that sweep of his bed, his open eye, his open mouth, that beautiful hand with a hint of gauze at the wrist, the color of it like marble, the full sense of it as flesh?” (In the Shadow of the American Dream, The Diaries of David Wojnarowicz)

“I can’t form words these past few days, sometimes thinking I’ve been drained of emotional content from weeping or fear. I keep doing these impulsive things like trying to make a film that records the rituals in an attempt to give grief form.” (Living Close to the Knives)

“It’s a dark and concrete bunker. There is a clump of three guys entwined on the long ledge. I had an idea that I would make a three-minute super 8 film of my dying friend’s face with all its lesions and sightlessness and then take a super 8 projector and hook it up with copper cables to a car battery slung in a bag over my shoulder and walk back in here and project the film onto the walls above their heads.” (“Spiral,” Memories that Smell Like Gasoline)

No super 8 reel of the dead photographer has been found since Wojnarowicz’s death, remarkably throwing it into question. The classicism of the reconstructed film Peter Hujar is aesthetically akin to the tone of Hujar’s work itself; dark stylized blacks, discreetly composed and juxtaposed images. The film resonates with the photographic, an insistence that Hujar’s work is seen; long, deliberate sequences of hands flipping through Hujar’s photographs, of Hujar as a child (in his journals Wojnarowicz describes returning to Hujar’s apartment after he died and spreading the photographs out on Hujar’s bed), reproductions of paintings of St. Sebastian (an echo of the earlier painting Peter Hujar Dreaming / Yukio Mishima: St. Sebastian, 1982) and then a panning shot, not actually of Hujar on his death bed but of the contact sheet of 35mm stills Wojnarowicz shot on that day. Rain falls into darkened puddles, onto already drenched streets, sheets of grief.

The unfurling of Hujar’s memorial quilt (with designs by Wojnarowicz, a close-up of a faceless man hugging a tree trunk in midair), a seemingly alien ritual that it’s terrifying to realize feels so historical. A William Burroughs/Anthony Balch-like dream sequence of a man sitting up in bed wearing a gas mask; a man, his head wrapped in bandages, walking up a staircase, is unbound in the glare of a light. Wojnarowicz made numerous super 8 reels and photographs of Mexican mummies (one of which is the hidden key to the as-yet-unrestored super 8 film Beautiful People (1988, 30:00 min.).

Overwhelmingly, there’s a powerful determination of Hujar’s existence (work, life) and a painful, profound fury at his death through the act of its telling and retelling. Vehemently, Wojnarowicz WITNESSED.

The circuit board of the painting Wind (for Peter Hujar) (1987) becomes a cycle of destruction, consciousness, creativity and rebirth that modifies traditionalist approaches; a set of personal signs manifesting, metaphysically, the whole of Hujar and social rage – a visual map that’s the site of politics, as indivisible as experience and expression, the acts of looking, feeling, of documenting, themselves political action.

“As time goes on I have come to believe that all things are not necessarily what they appear if you judge them only by their silence or invisibility.” (“Do Not Doubt The Dangerousness of the 12-Inch Politician” )

Heroin is a stylized apocalypse of addiction. A gang of people shoot up and variously collapse compounding prophecy, the record of a state of emergency, humour, profundity. In the seminal photographic series Arthur Rimbaud in New York (1978-9), the romantic similarly collapses onto reality; a guy wears a crude photocopied mask of the 19th-century French Symbolist poet and poses at various locations around New York; eating cake at Tiffany’s, at peep shows, on Coney Island, in the meatpacking district, shooting up in a Hudson River warehouse.

Much of Fire In My Belly is from Wojnarowicz’s many trips to Mexico. With overwhelming prescience, it’s divided into sections by the found drawing of a steam train (again, an icon repeated; Crash: The Birth of Language/The Invention of Lies (1986), Some Things From Sleep (1986), Time (1988-89)) that rushes closer and closer, and a growing number of tarot cards; a young kid breathing fire on the streets, Mexican wrestling, the circus, newspaper headlines of death, murder, destruction, Mayan temples and camera-wielding tourists, cockfighting.

A painted burning eyeball revolves like the earth against a bright blue background. A dirty hand catches money falling from just behind the camera lens. We think of the painting Fire (1987) (smoking volcano, a snake eating its own tail, a car battery, cartoon flashes, “wanted” posters), the sculpture of the pig’s skull covered in dollar bills and maps, an upside-down globe between its jaws (Untitled (1985)), the shot of bandaged hands barely cupping coins in the photomontage Silence Through Economics (1988-9). The discretion of the film’s cultural and social rage, the drive for an alternative, is enormous, imagination becoming the collation of evidence, a system defiantly flipped back on itself, a language.

“We are born into a preinvented existence within a tribal nation of zombies. Some of the tribes are in the business of sucker-punching people’s psyches. Then there are the tribes that suckle at the breast of telecommunications every evening after work. Day after day they experience waking nightmares but they’ve bought the con of language from the tribe that offers hope, or they’re too fucking exhausted or fearful to break through the illusion and examine the structures of their world.” (“In the Shadow of the American Dream” )

Without apology or concession to the common cultural lie of consistency, Wojnarowicz was a WITNESS, driving against a corrupt system of social control, legal, political and religious hypocrisy, railing violently against Cardinal John O’Connor’s Roman Catholic Church, Reagan’s America, his “One Tribe Nation” , and famously against the censorious National Endowment for the Arts. Articulated as lived (hustler, addict, artist), his means of expression were equally a means of resistance, subjective impulse and disjunction of register staking out a radical formalism.

This has been a doubly partial account: the provocation of Wojnarowicz’s body of work through a tiny proportion of reconstructed films and a few of their intersections. Relentlessly, that body reflects itself, refracts himself, his witnessing, his body, our structures. It DEFIES ASSIMILATION, constructing instead an integrated whole predicated on biography that’s by turn insistent, disarming, comprehensive. Radical, romantic formalism.” (Ian White, June 2002)

The Estate Project are a New York-based organisation who identify, document, preserve and make a record of works created by artists with HIV/AIDS.

Heroin, Fire In My Belly and Peter Hujar premiered at the 16th London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, April 2002.