Sunday July 17, 8PM

$8/ $5 Members & Students

@ Monarch Tavern, 12 Clinton Street

Part of Summer 2016

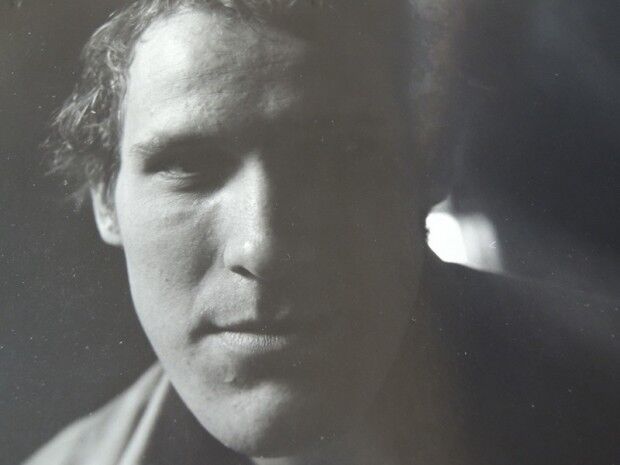

In February 2014 we lost our friend and long time fringe movie artist Mike Cartmell to cancer. His son Sam has been digging into his archives ever since, and has uncovered a secret website, mysterious writings, and a trove of never released movies which will be seen tonight for the first time. Guided by his love of Herman Melville and later, Lacan and Maurice Blanchot, Mike was an orphan whose identity quest was strained through critical theory, and whose movie work was literary, sensual and experimental.

Mike began making Super 8 films in the 1970s, made a quartet of movies around Melville in the 80s, completed an hour-long accompaniment to experimentalist American poet Susan Howe in the 90s, and worked for years on Shipwreck Theory, a multi-part vortex of translations and adaptations.

Trailer for Shipwreck Theory

The evening will be hosted by one of the many who considered Mike their best friend: Alan Zweig, who will tell tales and share never-seen-before Mike outtakes from his seminal movies Vinyl and I,Curmudgeon. Mike’s handsome new book Disasterologies, a collection of his essays and writings published by the Canadian Film Institute, will be available free to all comers.

Check out Mike’s website www.mikecartmell.com (it includes home movies by vincent grenier, video interviews by alan zweig, handsome selection of photos, texts by and about mike, as well as newly uploaded digital files/movies, research notes, grant applications, melville jottings, the works…)

Program:

Intro by Alan Zweig

video file: Mike Cartmell by Alan Zweig

Intro by Daniel McIntyre

What Talking Means 7 minutes 2006

The Star That Ought to Guide You 3 minutes 2005

O, Fortuna 14 minutes 2007

Intro by Mike Hoolboom

I Built a Cottage for Susan and Myself 11 minutes 1993

Intro by Sam Cartmell

Cartouche 7 minutes 1985 16mm

In the form of the letter ‘X’ 5 minutes 1985 16mm

What Talking Means by Mike Cartmell 7.5 minutes 2006

An old movie theatre intertitle reads “Patrons are requested to refrain from talking during the performance…” We hear Godard saying “Silence,” from the opening moments of Contempt (1963). Who is speaking, and who is remaining silent? Is talking made out of silence, the silence of the spectator, the words that can’t be said. Becky’s pregnant belly is the focus of the early, quick cutting montage, Jazzbo waits as a promise in her floating form. When the scene settles into a woodland interior cabin, a moment from their happier days together, a song says “I never will go back to Alabama,” a reference to their shared residence in Mobile, before their painful separation. She wants to tell him something, but she holds herself back. The quick montage from earlier in the movie repeats (a sexual scene, two boys sharing a secret look, birds passing overhead), before moments from Tarkovsky’s The Mirror (1975) are replayed, showing a stuttering teenager whose fractured subjectivity is reflected in his language. He is temporarily healed via hypnosis and repeats the words, “I can speak.” Becky returns as the sphinx, the “symbol of the symbolic,” still unspeaking as the camera waits. The secret of their shared child, and the two separations that have not yet occurred – between mother and son, and between the two parents. Are these unspoken separations, these cuts, “what talking means”?

The Star That Ought To Guide You 3 minutes

This orphaned work was part of Mike’s original Shipwreck Theory set, then temporarily set aside when he remapped the project. It opens with a Polaris missile, which was a missile built in two-stages, and was intended for use as a “second strike” counterattack. Doubles and doubling are at the heart of the matter here. The left screen replays Theo Angelopoulus’s contribution to the omnibus feature Lumiére and Company (1995) showing Ulysses waking from a long sleep and staggering towards the camera, looking deeply. On the right hand screen an older gent plays a stringed instrument (in two parts, the right hand makes chords while the left strums and picks), and sings “Troubles” a traditional folk song. “Oh lordy me, oh lordy my/See you when you haven’t got a dime/When your trouble is so deep that you can’t eat or sleep/See you when your troubles just like mine.” The title derives from the etymology of the word disaster, which means that the navigator, the sailor, is separated from the star that ought to guide one.

O, Fortuna 14 minutes 2007

A tale of Mike’s friendship with Mickus, sung up at the camp, the island getaway, the last mother, the picture divided as they were not, the lines of flight scrolling until Montaigne dies and then returns in order to birth the project of self-portraiture. The filmmaker practices death. Mike’s obsession with chiamatic doubling continues in the picture’s split, even as he heals it by running his touching comrade ode across it. “Even in your dying, and despite my state of wreckage, I was accruing benefits, coming closer than I had ever been to death, your death, watching you sink from the safety of the shore, and soaking up the knowledge to be had, the macabre poetry of it.”

Susan Howe

Mike struggled for years between his prodigious reading habits and his movie making hopes. How could someone so dedicated to the word make movies? In Susan Howe he found a mentor and transitional figure, someone who might help him reimagine a filmic avant-garde that held silence as its greatest virtue. Howe is a poet, essayist, critic, a prolific writer whose bold formal interventions have continually rubbed at the materiality of language itself, spraying and spreading words across the page in different constellations. One of the great poets of her generation. Their friendship deepened after Mike shared his love for Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil, an essay movie that became a clue for how they might proceed with their own work. An essay, a trial, an attempt, a collection of fragments. The essay was a forgiving form, open even to fringe poetics. The poet returns as a historian.

I Built a Cottage for Susan and Myself 11 minutes 1993

The question of an artist’s style haunts this miniature, which would provide the basis for his hour-long home movie Non-Compatibles (2002). Shot in a single afternoon, we see the poet at her desk in Buffalo, New York, speaking and gesturing, remarking on names (a favourite and shared preoccupation), the Hi8 camera glued to its digital solarization setting. A title overlay cribbed from Thoreau reads: “The talent of composition is very dangerous – the striking out the heart of life at a blow, as the Indian takes off a scalp.” It is an often repeated maxim, though we can see, in the fragments of page views offered later, that Thoreau describes a slaughter of Indians by white men, a slaughter that is then covered up by its reversal (it was the Indians who were scalped, not the whites). The poet sounds out words like gunshots from her desk, firing from the places that history has left behind too quickly, taking Thoreau apart word by word (from her book Singularities (1990).

Cartouche 7 minutes 1985

Cartouche is an audio-visual tombstone for his friend Cathy (Ca-thy, Ca-rtouche) whose pyramidical face is offered in between glimpses of Egypt and whaling and sex. A repeating phrase from the Sound and Light Show at the pyramids of Giza animate the work: “You have come tonight, to the most fabulous and celebrated place in the world.” In other words: a funeral. The cartouche was used to decode hieroglyphics on pyramids, they showed the name of the ruler in a circle. Once this name could be identified, it became the key to unlock the entire language. As if the name was at the root of language itself, or as Mike said more than once, “a language names you.” Ca-thy. A series of intertitles summarize the project: ca-tharsis, ca-thedral, ca-thexis. In the voice-over there are repeated conjurings of the figure “X” – “Cartmell” means a meeting place of carts, an intersection, a crossroads, an X. And Melville means a meeting place of villages, a crossroads, an X. The voice-over announces “You saw the crosspile outdoors.” It speaks of a double architecture, one above ground, one below, these two architectures meeting as if they were an X. I have no idea what this movie means, and I never get tired of watching it.

View In the form of the letter ‘X’>

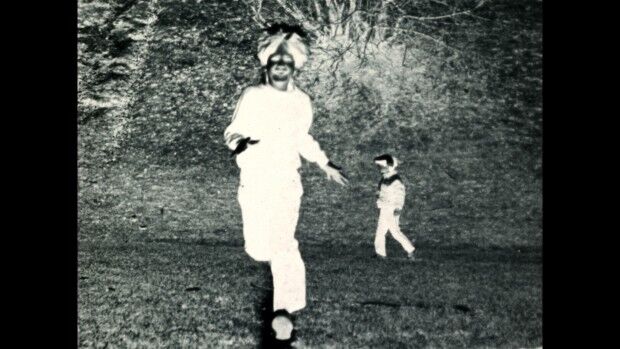

In the form of the letter ‘X’ by Mike Cartmell 5 minutes 1985

The second film in the series, In the form of the letter ‘X’ is a signature – a filmic equivalent of Cartmell’s name (which is reduced by exhaustive transcription to a simple X). X is the mark of those who cannot write, or who do not know their own names. Photographed over time against a backdrop of the Canadian Shield, X shows Cartmell’s son Sam running in slow motion towards the camera, and, in the film’s second half, away from it. The shape/structure of the movie is chiasmatic, part of the old avant-garde dream of creating movies that could be run backwards and forwards. The movie is in two parts that form an X. The music is taken from a Zombies tune whose opening riff is looped and repeated, held in suspension until the song breaks into its opening lines over the final image: “What’s your name? Who’s your daddy?” Intertitles lifted from Melville’s Pierre relate the tale of a graveyard search, a hunt through pyramids, only to find that the caskets are empty.