Part of Winter 2000

Over two evenings Pleasure Dome is pleased to present one of the truly unique forms of cinema – live improvisational cinema. From the earliest era of magic lanterns and musical/voice accompaniment of silent films, there has always been an improv cinema. The artists in this programme share an interest in experimenting with the notion of a “performative” cinema, either with improvised music and sound over a silent film or by treating the projected image as moveable and transmutable material. Join us for this re-interpretation of the early ‘magic lantern shows’ in an increasingly digital age.

Friday, February 18, 8 pm

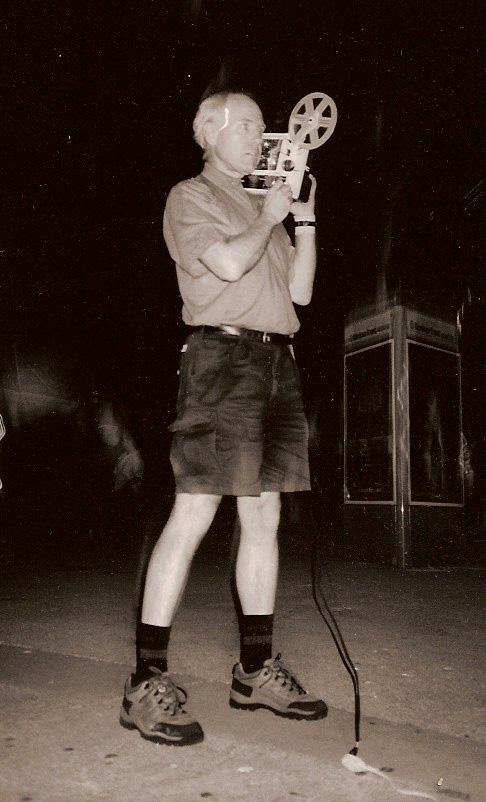

John Porter’s All-Request Film Busking

Scanning by John Porter (super 8, live projection)

Scanning is a super 8 film performance series which began in 1981. With projector in hand and films made for the occasion, Porter moves the moving images and dances with them around the room.

My Scanning series was inspired by earlier panoramic pieces by filmmakers Anne B. Walters from Chicago and fellow &lrquo;˜Funnel’er Ross McLaren, as well as my own panoramic work in film and photography. So far it has been a concept unique to small-format film, but now there are video &lrquo;˜palm-projectors.’ Video artists loosen up!

Scanning 1 (1981) is of the Funnel building at 507 King St. East (at Sumach St.).

Scanning 2 (1982) is a sync-sound film of the same building, with Funnel filmmaker Jim Anderson.

Scanning 3 (1982) is a black & white film of White St., in NYC, in front of the Collective For Living Cinema where I performed the film the night after shooting it. It features the Collective’s workshop co-ordinator Mary Filippo.

Scanning 4 (1983) is of the Morrisey Tavern on Yonge St., south of Church, with Funnelers Michaelle McLean and John Frizzell.

Scanning 5 (1983) was shot in Berczy Park at Front, Wellington and Scott Sts., with Funneler Dave Anderson.

Scanning 6 (1998) was shot in Craigleigh Gardens with Joe Behar.

Scott’s Scanning (1999) was shot at Hamilton College, Clinton, NY, with film teacher Scott MacDonald and his student Kyle Harris. I made it for Scott and after performing it at Pleasure Dome’s Open Screening last year, I sent it to him permanently to perform himself at any time in his future classes, so I can’t perform it tonight.

Scanning 7 (2000) incorporates Around the Corner (1977) and both were shot from the southwest corner of Yonge and Dundas Streets. Around the Corner was shot at Christmas just after the Eaton Centre opened. The 2000 scene was shot last Saturday, February 12, after buildings on the east side of Yonge had been demolished. I will shoot another scene after the new complex and public square is open.

A related work-in-progress tentatively titled Faces will be performed.

The First Recordist Improvisational Cinema by the Dept. of Recordist Film and Video (a division of the International Bureau of Recordist Investigation under the direction of W.A. Davison). Inspired by the work of the early Surrealists, this event presents a cinematic singularity not to be missed by fans of Recordism, Dada/Surrealism, experimental film, and improvised music. Through the application of chance and automatic processes, a one-hour Recordist/Surrealist film will be created through the real-time manipulation of random selections from a number of b/w silent classics while an ensemble of Toronto’s finest improvising musicians and audio experimenters (members of the Rust Bros., the Woodchoppers Assoc., Urban Refuse Group, and others) provides an amazing improvised soundtrack.

Saturday, February 19, 8 pm

Light Matters by Joost Rekveld

Based in Rotterdam, Dutch filmmaker/kinetic sculptor Joost Rekveld will present a selection of recent films that explore the abstract in the moving image. While studying composition of electronic music Rekveld was heavily influenced by the approach used by post-serial composers such as Xenakis. Rekveld’s most recent work is entirely based on spatial and temporal interferences, making use of very elementary mechanical scanning principles. “I started making abstract films out of a fascination with the sensual force of moving colour. I was intrigued by the abstract animated films of the 1930s and 1960s, and by scientific ideas about light from the turn of the century.”

film #3 (1994, 16mm, 4:00 min., silent)

#3 is a film with pure light, in which the images were created by recording the movements of a tiny light source with extremely long exposures, so that it draws traces on the emulsion. The light is part of a simple mechanical system that exhibits chaotic behaviour.

IFS-film (1991-4, 16mm, 3:00 min., silent)

A computer film based on visual pixel noise which in theory contains all possible images.

VRFLM (1994, 16mm, 2:00 min, silent)

A short study on the optical printer based on a piece of found footage, partially destroyed film stock and pure light.

Beat Time (from Sonic Fragments) (2000, video, approx. 8:00 min.)

Sonic Fragments is a follow-up to the Sonic Images project of two years ago, in which six filmmakers were invited to collaborate with six composers. The concept is to make remixes of the material contained in these six original films, according to very diverse strategies. The project contains remixes by Ian Kerkhof, Frank Scheffer, Alexander Oey, Rob Schrder, Miriam Kruishoop, Mischa Klein and Joost Rekveld. Beat Time tries to establish a connection between material taken from ‘Sonic Images’ and the development of moving image technology. It is an attempt to deal with the different perspectives inherent to the way media deal with time. The composition is based on a spectrum of frequencies: the frame-rate of film, the line-frequency of television and finally the dark vibrating world of pixels.

film #5 (1994, 3 x 16mm, 6:00 min, silent)

#5 is a film for three projectors and three independent screens next to each other. The images were created by shooting moving reflecting forms with widely varying exposure-times. These images were then printed on the film-strip in various ways. The film explores the relation between image and time on the film-strip and modulates continuously between what I regard as two extremes in this respect.

installation #19 (1999, film performance with music, c. 20:00 min)

#19 is an installation in which images are produced through interference. The interplay between the time lag of our eye and the fast rotation of a pulsating light source results in ever-fluctuating ornaments.

film #7 (1996, 16mm, 32:00 min, silent)

#7 is a film that was made by stamping paint onto transparent film and using the result of this as a negative. The colours in the film modulate from black via the primary light-colours and via the primary paint-colours to white. All movements in the film are caused by the interference of the stamped grid patterns and the perforation of the film material.

Based in Rotterdam, Dutch filmmaker/kinetic sculptor Joost Rekveld has been making abstract films since 1992 and kinetic installations for the past three years. “I started making abstract films out of a fascination with the sensual force of moving colour. I was caught by the abstract animated films of the thirties and sixties and by the ideas about light art from around the turn of the century. A concept which pervades both of these kinds of moving art is the idea of a form of composed light which can be compared to the way sound is structured in a musical piece. I began by studying musical composition in order to develop my soundtracks, increasingly I started to apply the compositional approaches I learned to the visual structure of my films. The way of thinking of the post-war serial composers was a big influence on me, especially in regard to the way they construct a piece on the basis of parameters. For them, these parameters usually were fundamental aspects of sound, like pitch, duration or timbre. While thinking about similar fundamental aspects of composed light, I increasingly turned towards the technical foundations of the film medium. This resulted in a number of films and installations in which the images were generated by the interference between several movements, or which were based on elementary principles of scanning. This made me think differently about technology. Instead of a neutral means to an end, technology is a part of our culture just like art or mythology. In the history of technology specific motives recur in ever changing constellations, motives which often originated in philosophy or art. Also the contemporary disgust or devotion to technology stands in no proportion to the supposed mere functionality of it. The rift that many perceive between the world of ‘cold’ functional science and technology, as opposed to the ‘human’ world of art and intuition, is in my opinion based on a dangerous misconception. The full exposure of the sensory and human aspects of technological motives has gradually become one of the main aims of my work.” From 1989 until 1993 Joost Rekveld was an organizer and programmer with the Impakt-festival, an annual festival for experimental film, music, video and installations in Utrecht, Holland. Since 1996 I have been curating thematic programmes within the festival: The Film and Perspective programme in 1996, and the Element of Time programme in 1997. Also I have been involved in the selection of work for the Panorama section. For a full list of Rekveld’s films visit http://www.xs4all.nl/~rekveld/listfr.html.

Figural Disfigurations: ‘Folding Back on Itself’ by Luis A. Recoder

Figures of speech in which language performs a series of contortions and disfigurations on language itself is grounded in the physical world, giving rise to a rhetoric of metaphor and metonymy. In the cine-objects of filmmaker Luis A. Recoder dis-figurations are re-grounded in the materials of film. The passage of filmstrip through the projector is a passing-over into objecthood. By twisting the film so that it “double-crosses” itself, the transparent ribbon is thickened, crowded and populated by its multiple and contradictory “selves.” Can one speak of film as having a “guilty conscience,” driving it to the point of “turning itself in?” Or a film that returns to “lick its wound” as if coming to terms with its already disfigured self. How to project this impossible density, this circuitous cinema spiraling in on itself? Or perhaps less demanding, how to reconcile the path of impressions with that of its projected though suppressed persistence of impressions? (Luis A. Recoder)

Magenta (1997, 9:00 min.)

Light Sensitive (1999, 7:30 min.)

Ballad Of… (1997, 25:00 min.)

Untitled (1999,16:00 min.)

Color Slides (1998-99, 6:00 min.)

Moebius Strip (1998, 13:00 min.)

“Bay area filmmaker Luis A. Recoder has been creating a sensation with his projection performances using multiple strips of film fed into a single projector or an array of projectors with duplicate prints. Following the sinuous wind of the film path and playing the same film against itself, Recoder coaxes frictionless harmonics out of closely contrasting imagery, infusing a new element of time into timeless replay. Imagine Buster Keaton’s phantom projectionist in Sherlock Jr. wandering into the booth of the movie theater of Raul Ruiz’s Life Is a Dream, infecting the film itself with the contagious spirit of doubling and concussive space. As in early cinema at the turn of the century, Recoder foregrounds the magical and the mechanical notion of the apparatus. These pieces conjure up a beguiling spectacle using delicate manipulations and elegantly simple technical daredevilry. Working with found footage, Recoder creates dense and purposeful derangements of his material – not through physical editing but at the level of audio-visual delivery, achieving “live” effects that would normally be safely committed to a single strip of film through optical printing. Reshaping light and disorienting our sense of space (scale, location, solidity, volume, transparency, geometrical composition), color and time. The multiple superimpositions that spiral out of the fabric of these bipacked filmic “compresses” activate in the viewer a kind of visual calisthenics, playing with our short-term memory sense of déjà vu through antiphonal echoes of sound and image. Recoder reconciles two of experimental cinema’s polar approaches towards the use of found footage – deviation from the original intentions of source material through extensive editing-collage and the “immaculate conception” of presenting appropriated work in a new context but in a physically unaltered form. Transcending the usual provoking of casual surprise and the haphazard yield of chance encounters with discovered materials, Luis Recoder’s discriminating vision shapes the film into new works that are surpassingly uncanny, as compellingly complex as Baroque fugues and action packed.” (Mark McElhatten)

Luis A. Recoder is a San Francisco-based conceptual filmmaker making films on the faultline between thought and practice. His pact with the material conditions of his medium seeks to disrupt its “fetishistic turn” in the face of technologies of “dematerialization.” Recoder’s work was recently presented in a one-person screening at the Lincoln Center in New York. His work is included in the recent exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, The American Century.