Part of Winter 2005

A co-presentation with MOCCA

Pleasure Dome and MOCCA are pleased to co-present the downtown premier of Bruce LaBruce’s The Raspberry Reich. On Friday, February 25th, Bruce LaBruce will introduce his most recent film and will participate in a post-screening discussion with Noam Gonick and John McCullough. Gonick is a Winnipeg-based filmmaker who studied with Guy Maddin and Bruce LaBruce, producing a documentary and book on their work before making his own films; McCullough is a writer and Super 8 filmmaker who teaches in the Department of Film & Video at York University. The post-screening party will feature DJ Rory Them Finest and Cheerleader 666. The Raspberry Reich will be shown again at 7 and 9 pm on Saturday, February 26th.

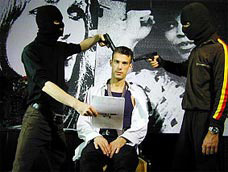

The revolution is my boyfriend! Local queer punk pioneer and Pleasure Dome favourite Bruce LaBruce is back after the controversial Skin Flick with his latest atrocity exhibition, the raucous The Raspberry Reich. Now skewering far left instead of far right, LaBruce has thrown together a rich cinematic swill of Godardian sloganeering, hardcore queer porn and witty jabs at radical chic. The Raspberry Reich follows the adventures of a gang of extreme left terrorists who model themselves on the hot young things of the Red Army Faction/Baader-Meinhof Gang fighting it out for an anti-capitalist (by way of sexual) revolution. Gudrun, the self-righteous terrorist leader is the charming, Wilhelm Reich-following blonde dictator of a bevy of boy-toy minions. At Gudrun’s insistence her male followers (porn stars one and all) go gay for the greater good. They plan to kidnap the son of a wealthy German industrialist, but libidos and incompetence get in the way and mayhem ensues. A messy camp manifesto for public sexual warfare and a mockery of knee-jerk rebellion and fashionable causes, the typically irreverent and chaotic The Raspberry Reich is both agit-prop and fuck flick.

Alan Dale on The Raspberry Reich

“In her 6 April 1968 New Yorker review of Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise, Pauline Kael began:

A few weeks ago, I was startled to see a big Pop poster of Che Guevara – startled not because students of earlier generations didn’t have comparable martyrs and heroes but because they didn’t consider their heroes part of popular culture, though their little brothers and sisters might have been expected to conceive of them in comic-strip terms.

Well, we’re way past being startled anymore, I should think. In Bruce LaBruce’s The Raspberry Reich, a small band of left-wing terrorists in contemporary Berlin have incorporated the radicalized student generation of the ’60s that Godard made movies about, “the children of Marx and Coca-Cola” as he put it, into their romanticized pop politics right alongside Che. LaBruce’s little sect models itself on the German Red Army Faction (the “RAF”), a/k/a the Baader-Meinhof gang, perpetrator of terroristic crimes in the ’70s. The head of the group, and its only female member, calls herself Gudrun after Baader-Meinhof member Gudrun Ensslin and dons a blonde wig in order to more closely resemble her as she spews slogans to the impressionable guys under her.

Gudrun’s ideological base is Marxist, of course, but she tilts toward Wilhelm Reich and Herbert Marcuse’s individual blends of historical materialism and psycho-sexual theory. In this light she has updated Karl Marx’s formulation, “Religion is the opiate of the masses.” Shaking her synthetic mod locks she cries, “Heterosexuality is the opiate of the masses!” to which one of her confused boys replies, “I thought opium was the opiate of the masses.” (The funniest variation on the original since “Marxism is the opiate of the intellectuals.”) Pushing a recalcitrant boy toward her idea of revolution, Gudrun insists, “It’s time for you to put your Marxism where your mouth is and help us initiate the homosexual intifada.”

In “honor” of the RAF’s kidnaping and murder of Hanns-Martin Schleyer, an industrialist with a Nazi past, Gudrun plans the abduction of the son of an industrialist. She had previously forced her own companion Holger to have sex with Che, the masturbatory gun fetishist of the group. (When Holger objected, “But I’m your boyfriend,” she exulted, “The revolution is my boyfriend!”) She now forces one of the gang to have sex on video with the captive, who, it turns out, is perfectly willing. He’s actually been trying to escape from the old man, who wants to institutionalize him and subject him to a “cure” for his homosexuality.

Her radical enterprise falls apart because Gudrun doesn’t perceive or can’t control the drives she stirs up. Some of the guys turn out to be more sexual, some more criminal, some more conventional, than is good for a group of supposedly dedicated terrorists. Gudrun isn’t really paying attention–she’s theorizing, with exclamatioin points. Gudrun’s revolution is 1% theory and 99% exhibitionism, combined in a way meant to impress, cow, and stimulate her followers, not to persuade them, or anybody else. In the end all she’s exhorting the guys to do is screw, play with guns, and shoplift. It wouldn’t take even 1% theory to get some guys to do this.

But when the gang’s plans go awry, Gudrun the survivor follows Holger, who always wanted only to marry her, confine their sex to the bedroom, and have kids. We last see Gudrun pushing a stroller and telling little Ulrike (as in Ulrike Meinhof) the same “glorious” stories of the RAF she had bored the boys to distraction with a few years earlier.

The movie is full of details about the notorious terrorist cells of the ’70s, including the infamously ragtag and incompetent Symbionese Liberation Army, but as LaBruce’s dialogue indicates, this is not a realistic recreation (unlike Paul Schrader’s fine Patty Hearst (1988)). The Raspberry Reich makes no attempt to stage the action realistically, and it’s like a vacation from the suspension of disbelief. LaBruce owes a debt to La Chinoise, which was “difficult” and broke through generic categories but remained culturally “respectable.” But The Raspberry Reich, repetitive, disorderly, and flagrant, has more more in common with the work of underground professional amateurs, like Kenneth Anger, Andy Warhol, Paul Morrissey, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and John Waters, than with the work of Godard.

Godard was comfortable with actors and movie stars. LaBruce isn’t interested; he wants the characters to seem fake. As he says in this interview with Filmmaker Magazine, “[S]ome people who don’t understand my films, they’ll go, ‘Well the acting was really bad.’ Well, who cares? I don’t care if the acting was bad. That’s not the point – or that was the point!” The movie is in English, but the actors aren’t native speakers. It shifts back and forth between Gudrun’s tirades and more intimate conversational scenes among the boys, and though Susanne Sachsse, who plays Gudrun, is a stage actress she doesn’t have the command of English to put the rhetorical flourishes across, and the boys’ scenes are never more than thinly realized. LaBruce cultivates the inevitable awkwardness in the first place because the clumsiness and obviousness function as satire of Gudrun (who can’t see, as we can, that her theories aren’t working out as she imagined). LaBruce’s use of camp is thus fairly complex but still as entertaining as if Gudrun had been played by a nothing-to-lose drag queen.

If anything puts the movie over, it’s the big laughs LaBruce gets from the wigged-out radical sloganeering. One of two gangmembers on a couch watching TV scoffs that Gudrun thinks cornflakes are counterrevolutionary, and the other boy (with whom he’s about to have sex) says, “Cornflakes are counterrevolutionary!” and explains how. Even better is when Gudrun (overcompensating for her German accent) convinces Holger and Che to steal from a mom-and-pop grocery store instead of a corporate chain by reasoning: “Sometimes the exigencies of the revolution necessitate the adwancement of praxis over theory.” I was an undergrad in Berkeley in the early ’80s where adherents of every conceivable revolutionary lunacy said similar things with utter self-seriousness. (One bitterly unhappy young woman claimed that the taboo against incest was an oppressive, bourgeois-patriarchal construct. She has since committed suicide, and who can wonder.) For me, LaBruce gave vent to years of disbelief with this florid-yet-deadpan clowning.

The awkwardness of the boys is somewhat different. If their “bad” acting seems to be of a familiar type it’s because they’re all actual porn stars. When it comes to breaking through generic categories LaBruce puts Godard in the shade; the most offputting aspect for most moviegoers, no matter how cosmopolitan, would have to be that The Raspberry Reich includes explicit sex, money shots and all.

These scenes would be considered “gratuitous” by conventional narrative standards (and I don’t just mean Hollywood standards) and they can’t be said to work in terms of the characters or story–supposedly hesitant guys finish off their first acts of gay sex not only with gusto but evident expertise. LaBruce, who directed the controversial skinhead-fetish porno movie Skin Gang (2000), doesn’t justify the sex acts, which can be enjoyed for their own sake (the guys are as unrealistically good-looking as in any gay porn). His immediate intention is to prevent the movie from being a user-friendly consumer item. But the sex scenes also function more generally (as they do in the Marquis de Sade’s incomparable Philosophy in the Bedroom) to keep you aroused in ways you usually aren’t while thinking.

LaBruce is often referred to as a “provocateur,” and in interviews he glorifies the freedom (conceived in terms of permanent adolescence) that he got from the punk movement. He seeks a revolution that keeps on revolving. So he’s turned off by a gay movement that focuses on integration into middle-class monogamy and finds even gay porno movies too conventional. (As he says in the Filmmaker interview: “Everything is contrived to present the illusion of sex spontaneously unfolding before your eyes, but it’s actually extremely calculated. It’s an industry, so you are pushing out this product.”)

Thus, the irony of The Raspberry Reich is that whereas LaBruce plainly satirizes the sloganeering Gudrun, he shares a fair amount of her ideas. Here he is at his most inappropriately humorless: “In [The Raspberry Reich] one of the slogans is ‘Madonna is Counter-Revolutionary,’ and I do mean that literally…Madonna…zeroes in on revolutionary moments (usually gay and/or black subcultural manifestations), but with the strategy of co-opting, neutralizing, commodifying, and ultimately exhausting and abandoning them. She is the ultimate example of someone who uses radical chic for exploitative and purely capitalistic ends.”

LaBruce couldn’t have written Gudrun’s lines if he didn’t see what was funny about a walking, talking revolutionary doll. But he’s more disappointed in what this bodes for revolutionary politics than he is disgusted or even amused. As he says in this interview posted on the website This Is Baader-Meinhof:

The platforms of the ultra left wing terrorist groups which emerged from [the student protest movements of the ’60s] were based on these humanist, egalitarian ideals. They believed, however, that any ends justified the means to achieve these goals, which placed them in morally untenable situations, eventually rendering them almost indistinguishable from their avowed enemies. (The oppressed becoming the oppressor is a theme that runs throughout my movies.)

With The Raspberry Reich I wanted to revisit these ideas and sentiments in a more modern context. After 9/11, particularly in North America, the left was castrated and rendered virtually silent. I wanted to make a movie that gave voice once more to the left wing, anti-corporate, anti-capitalist rhetoric that was once part of the public discourse but which had become completely absent. The movie also operates as a critique of the left, skewering people who either don’t practice what they preach, or who become so self-righteous and intractable in their beliefs that they themselves become oppressive and dogmatic.

Clearly, LaBruce would see someone like Gudrun as having fallen off from a radical ideal.

This formal statement of his intentions, however, doesn’t describe how the movie plays, in part because it doesn’t account for LaBruce’s rejection of professional moviemaking polish and discipline. But what happens onscreen also supports what I noticed in Berkeley, that the politics were always secondary to the gratification the leaders of the group drew from controlling the interpersonal dynamics. (In addition, the political theories, with no experience-testing behind them, and perhaps none possible, were illusory, never more obviously so than when they were carried into the streets, but LaBruce doesn’t consciously go that far.)

LaBruce even holds repugnant views, such as this bizarrely unconvincing rationalization from an interview with Kultureflash:

The misguided notion that homosexuality is forbidden in Middle Eastern and Arab cultures is a really good example of how the west completely misinterprets Muslim attitudes and practices. Only when homosexuality becomes overt or organised is it severely punished. But although you pick up on LaBruce’s commitment to oppositional ideology in The Raspberry Reich, it doesn’t kill the movie, as it killed Godard’s work after 168. LaBruce himself says in the Filmmaker interview:

I was starting to get too ideological, and I was trying to make very specific ideological points about sexual representation and the objectification of women, and I realized, as a filmmaker and as an artist–because I had a background as a critic, from film theory–I had to just drop all of that theory and just go more by instinct and not try to figure out where these images or the impetus of my work was coming from, and to just let it come out without thinking about it so much.

Well, in The Raspberry Reich out it comes and no one can stop it. LaBruce has an anarchic, pleasure-seeking instinct that jargon and theories can’t hold out against. (Pleasure and dogma occur in almost the reverse proportions from Alfonso Cuarón’s punitively moralistic escapade Y tu mamá también.) I’m pretty sensitive to left-wing censoriousness, to revolutionaries’ indifference to practical experience and individuality, and I can say unequivocally that it’s possible both to laugh like a hyena at the satire in The Raspberry Reich and to get off on the dirty bits, sometimes simultaneously.

With Sachsse’s Gudrun LaBruce captures that naked-bulb glare and buzz of personality you used to get in underground movies, but overall The Raspberry Reich doesn’t feel druggy or aimless or desperate or even inwardly obsessional. LaBruce leans towards the wordy-critical perspective of Godard (with phrases flashing on, and scrolling across, the screen) but his method plays more like the camp carelessness of John Waters. In the opening, for instance, Gudrun forces Holger to have sex with her in the elevator of their apartment building; an older couple threatens to call the police but once back in their own apartment the infection hits them and they have wild sex on their kitchen table. Later, Holger and Che, who really take to this gay sex thing, are all over each other in public while German matrons, candidly caught on film, glare and mutter. For all his ideological commitment, LaBruce seems to have as much fun stealing footage in public as Mack Sennett and his Keystone jokers did in the 1910s with their totally unambitious comedy shorts.

In many ways The Raspberry Reich is a defiant mess, which I mean as praise. Why should you care whether the actors sustain the illusion of being the characters, whether the director keeps his crayon within the lines? Are you ever unaware you’re watching a fiction film? I also prefer blatant porn to the coy prick-teasing central to American pop entertainment. LaBruce may not be absolutely “right” in all his choices, and sometimes his needle gets stuck in a groove, but despite a totally rambunctious id and a heedless rejection of propriety, the movie holds together analytically. You won’t miss the point but at the same time what’s onscreen feels arrived at intuitively, which is why the movie can cohere without conforming exactly to LaBruce’s intentions as he articulates them in interviews. He’s probably the kind of “revolutionary” spirit who can’t be contained in any program. Thank goodness. The Raspberry Reich is as thoroughly, gleefully disreputable a work of political critique as you could hope for.”

Alan Dale is the author of What We Do Best: American Movie Comedies of the 1990s and Comedy Is a Man in Trouble: Slapstick in American Movies.

Bruce LaBruce is an independent filmmaker and writer whose features have developed an international following. His most recent film project, Skin Flick, was released in both hardcore and softcore versions, the former of which was nominated for nine gay adult video awards, the latter of which has played at over thirty international film festivals. Prior to that, his feature film Hustler White, a collaboration with Los Angeles based photographer Rick Castro, premiered at the 1996 Sundance Film Festival, followed by screenings at the International Film Festivals in Berlin, Dublin, Copenhagen, Thessaloniki, Toronto, Vancouver, Helsinki, Slovenia, Gijon, Lille, etc., and at Gay and Lesbian Film Festivals including Tokyo, Sao Paulo, Milan, Oslo, San Francisco, London, Barcelona, Melbourne, etc. Hustler White won first prize at the Freak Zone Film Festival in Lille in 1997, earning it a screening at the Cannes Film Festival. LaBruce co-stars in this romantic comedy with actor/supermodel Tony Ward. Hustler White has been picked up for distribution worldwide, including Great Britain, France, Spain, Germany, Australia, U.S.A, Canada, and Japan, and has been sold to television in Germany, Hong Kong, and England. In January 1996, LaBruce’s most recent music video, for the song “Misogyny“ by popular Toronto band Rusty, was the most requested video for three consecutive weeks on City TV’s MuchMusic and won a MuchMusic video award for Best Concept Video in 1996. His follow-up video for the song “Empty Cell“ also by Rusty won him the Best Concept Video Award for 1997. In 1994 and 1995, LaBruce traveled extensively with his second feature, Super 8 1/2, which became a hit on the international film festival circuit, playing at well over fifty festivals including Sundance, The Toronto and Vancouver International Film Festivals, London, Edinburgh, Dublin, Wales, Thessaloniki, Helsinki, Copenhagen, Rotterdam, Rio De Janeiro, Vienna, and Atlanta, as well as numerous Gay and Lesbian Festivals including San Francisco, Austin, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Paris, etc. LaBruce also traveled the world with his first feature, No Skin Off My Ass, which was shot on super 8 film and blown up to 16mm, debuting at the London Film Festival. No Skin Off My Ass and Super 8 1/2 have been picked up for distribution by Strand Releasing (North America), Stance Co. (Japan), and Dangerous To Know (UK); each of these distribution companies acted as executive producers for his latest film, Hustler White. Based on the success of Hustler White in France, the distributor Star Productions had more recently picked up No Skin Off My Ass and Super 8 1/2 for distribution. LaBruce has been working in collaboration with Berlin-based producer Jurgen Brüning since 1990. Before his affiliation with Bruning, LaBruce organized a screening of his super 8 experimental films along with those of G B Jones, Candy Parker, and others, entitled “JDs Film Nite” , which played at the Purple Institute in Toronto, at the Montreal Gay and Lesbian Film Festival and the London Film Festival. His work has been premiered in Toronto exclusively by Pleasure Dome.

Bruce LaBruce started out as Bryan Bruce, a film academic who received his Masters Degree in film theory at York University as well as the Famous Players award for best film studies student. He was also an original member of the editorial collective of CineAction! magazine for which he wrote for six years, acting as coeditor of two issues. While finishing his Masters thesis (on Hitchcock’s Vertigo), Bruce started to get involved in underground publishing and filmmaking, where his alter ego, Bruce LaBruce was born. LaBruce emerged as the co-editor of JDs, the influential gay punk fanzine which begat the “queercore” movement, before launching an international film career.

As a writer, Bruce LaBruce has contributed to such publications as CineAction!, Movie, Sight and Sound, MaximumRocknRoll, Index, Attitude, Vice, the National Post, the London Guardian, Honcho magazine, etc., as well as the anthologies Out in Culture, A Queer Romance, Anti-Gay, and Take My Advice. His popular column “BLAB“ has appeared for many years in Exclaim, Toronto’s monthly independent music magazine. More recently, he writes a bi-weekly column for eye weekly, Toronto’s Free Weekly. In 1997 the collective columns of Exclaim were expanded and published by Gutter Press in book form as The Reluctant Pornographer. LaBruce has collaborated as writer and performer with drag star Glennda Orgasm on six episodes of “Glennda and Friends“, the popular Manhattan cable TV show which has been screened at galleries and festivals world-wide. In 1996, LaBruce was invited to the Plug-In Gallery in Winnipeg, Manitoba for his first retrospective, co-sponsored by the Winnipeg Film Group. This resulted in a book from Plug-In Press of scripts, frame enlargements, and essays on LaBruce’s work. Other international art spaces which have shown LaBruce’s work include Pleasure Dome, A Space, YYZ, and the Purple Institute in Toronto, The Institutes of Contemporary Art in Boston and London, and the LACE gallery in Los Angeles. His films have shown at numerous major universities, including MIT, Harvard, Northwestern, and the University of Toronto, and he has appeared as a guest lecturer at York University and MIT. Ever expanding his repertoire, LaBruce has recently become a regular contributing photographer and writer for Index, Inches and Honcho magazines in New York and was recently named a contributing editor to Index. A book of his photographs will be published by Index in September 2001. Labruce has had solo photographic exhibitions thus far at the Alleged Gallery in New York, the Helen Pitt Gallery in Vancouver, and MC MAGMA gallery in Milano, Italy. LaBruce has had film retrospectives at such international film festivals as the U.S. Film Festival at Dallas, the Mix Festival in Sao Paolo, Brazil, and the Third Annual Buenos Aries Independant Film Festival in Argentina. Most recently, Labruce has participated in Platinum Oasis, an art/performance event held in Los Angeles in July. He presented installations there in July of 2001 and July of 2002. His most recent photo exhibition was in San Francisco at peres-projects in September, 2002. In September of 2003, LaBruce opened his latest exhibition of photographs at John Connelly Presents… in New York’s Chelsea art district. The show was called “Blame Canada“.